The box is the central metaphor of Joseph Cornell’s life, just as it is the signature element of his exquisite and disturbing body of work, his factory of dreams. He made boxes to keep wonders in: small wooden boxes that he built in the basement beneath the small wooden house he shared with his mother and disabled younger brother, the two fixed stars of his existence.

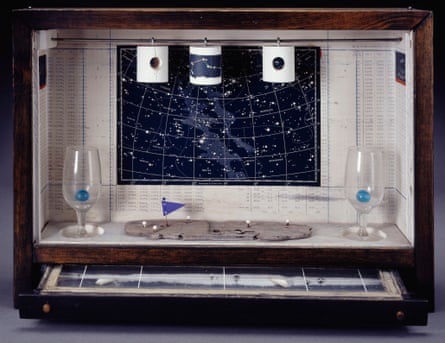

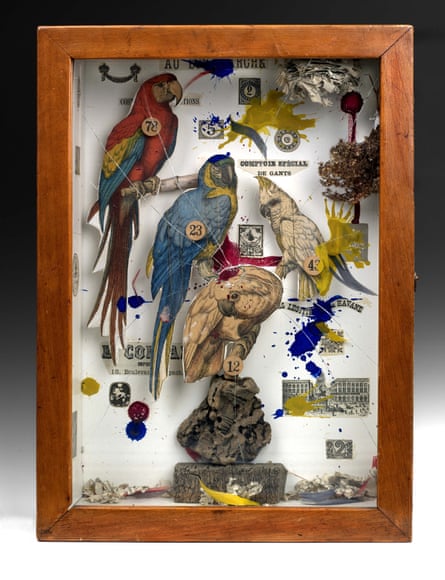

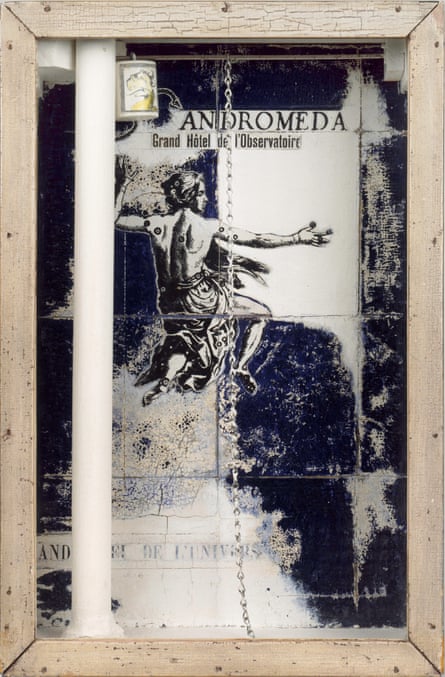

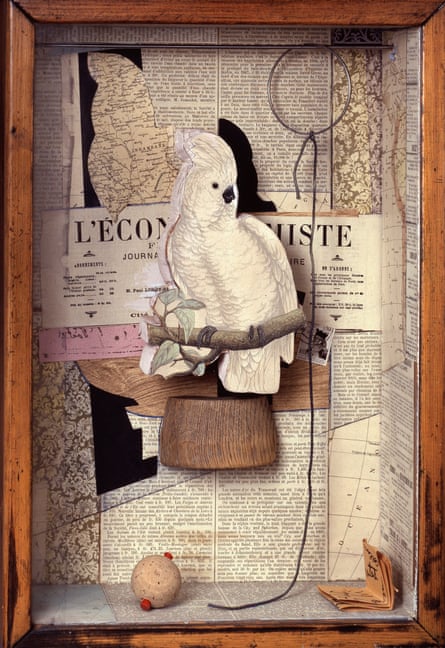

As a boy, he saw Houdini perform in New York City, escaping from locked cabinets, wreathed in chains. In his own artwork, which he didn’t begin until he was almost 30, he made obsessive, ingenious versions of the same story: a multitude of found objects representing expansiveness and flight, penned inside glass-fronted cases. Ballet dancers, birds, maps, aviators, stars of screen and sky, at once cherished, fetishised and imprisoned.

The same tension between freedom and constriction ran right through Cornell’s own life. A pioneer of assemblage art, collector, autodidact, Christian Scientist, pastry-lover, experimental film-maker, balletomane and self-declared white magician, he roved freely through the fields of the mind while inhabiting a personal life of extraordinarily narrow limits. He never married or moved out of his mother’s house in Queens and rarely voyaged further than a subway ride into Manhattan, despite being besotted with the idea of foreign travel and particularly with France.

He was on friendly terms with almost every artist who passed through New York during the middle years of the 20th century – among them Duchamp, Motherwell, Rothko, De Kooning and Warhol – and yet he was also profoundly solitary, a hermit who said to his sister regretfully in the last conversation they ever had, “I wish I hadn’t been so reserved.” Though he longed for larger horizons (the title of the retrospective currently at the Royal Academy in London is Wanderlust), he didn’t attempt to physically escape his circumstances, choosing, rather, to master the hard knack of conjuring infinite space from a circumscribed realm.

Cornell was born on Christmas Eve 1903 in Nyack, a village just up the Hudson from Manhattan. Nyack was also the childhood home of Edward Hopper, another rangy, solitary artist fixated with scenes of voyeurism and enclosure (though they didn’t meet, he taught one of Cornell’s sisters to draw at summer school). In 1910, Cornell’s beloved brother was born. Robert had cerebral palsy, struggled to speak and later used a wheelchair. From the beginning, Joseph considered him his personal responsibility.

The family’s early years were a whirlwind of Christmas parties and trips to the enchanted playgrounds of Coney Island and Times Square. But in 1911, Cornell’s father, an exuberant textile designer and salesman, was diagnosed with leukaemia. When he died a few years later it became unhappily apparent that he’d been living well beyond his means. Confronted by sizable debts, Mrs Cornell sold up and moved the family to New York City, renting a succession of modest houses in working-class Queens.

She wangled her oldest son a place at the prestigious Phillips Academy, but he was unhappy and friendless there and left in 1921 without so much as a diploma to his name. Unable to draw or paint, he had no notion of becoming an artist and that autumn took the first of many grinding jobs as a salesman in Manhattan. He hated the work and often suffered from physical ailments, among them migraines and stomach aches.

What leavened those years was the city itself. Any free time Cornell had was spent luxuriating in what he described as “the teeming life of the metropolis”. He prowled the avenues and lingered in the parks: a gaunt, handsome man with burning blue eyes, leafing through racks of secondhand books and old prints, haunting flea markets, movie houses and museums, pausing sometimes to feast on stacks of doughnuts and prune twists.

The city he favoured was neither glamorous nor exclusive, but democratic: an arcade whose astonishments might equally be found at a Saturday matinee at the Metropolitan Opera or in the lit boulevards of Woolworth’s. He built up a vast private museum from his excursions, toting home treasure in the form of rare books, magazines, postcards, playbills, librettos, records and early films. Stranger things, too: shells and rubber balls, crystal swans, compasses, bobbins and corks.

First, you acquire the materials and then you put them together. Cornell’s career as an artist began when he encountered surrealism in the early 1930s. The touch paper was La Femme 100 Têtes by Max Ernst, a collaged novel that introduced him to the idea that art was not necessarily a matter of applying paint to canvas, but could also be made from real objects, estrangingly combined. Inspired, he began to make collages of his own, sitting with scissors and glue at the kitchen table of 37-08 Utopia Parkway, his home from 1929 until his death in 1972. He worked mostly at night, his mother asleep upstairs and Robert dozing in the sitting room, surrounded by model trains.

In this period, Cornell also began to assemble what he called dossiers on his favourite subjects: folders crammed with cuttings and photographs of the ballerinas, opera singers and actresses he worshipped, among them Gloria Swanson and Anna Moffo. Other explorations, which sometimes ran for decades, were meticulously catalogued by way of topic: Advertisements, Butterflies, Clouds, Fairies, Figureheads, Food, Insects, History, Planets. Categorisation mattered to Cornell, though so, too, did intuitive leaps and flights of fancy. “A clearing house for dreams and visions,” he called his files – part research project, part devotional act.

By the mid-30s, he’d discovered the two great mediums of his maturity: shadow boxes and films made by re-editing found footage. One of the most striking among the latter was Rose Hobart, which he made by chopping up the B movie East of Borneo and splicing it back together as a series of lingering, blue-tinted glimpses of the actor Rose Hobart, wrapped in a trenchcoat, intercut with enigmatic footage of jungle foliage and swaying palms. According to Deborah Solomon’s biography, Utopia Parkway, at the first screening Salvador Dalí was so overcome with jealousy that he knocked over the projector, an incident Cornell found abidingly distressing.

Because of his lack of a formal art education and the unusual nature of his domestic situation, Cornell is often depicted as an outsider artist, but he was in the swim of things from the start. His early collages appeared in the groundbreaking Surréalisme show at the Julien Levy Gallery in Manhattan in 1932, alongside Dalí and Duchamp, and his first shadow box, Untitled (Soap Bubble Set), was in Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism, a major exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1936. Other artists were quick to see the value of his inventions (something that continued through the successive waves of surrealism, abstract expressionism and pop art). Despite his shyness, Cornell developed sustaining friendships, though he was never wholly comfortable with the business aspect of art.

In the winter of 1940, he took the bold step of resigning from his job. He set up a studio in the basement and began to concentrate on boxes, a project that would occupy him for the next 15 years. The early versions used readymade cases, but he soon began to build the frames himself, learning by trial and error to make mitre joints and use a power saw. Next, he’d age the box with multiple layers of paint and varnish, sometimes leaving them in the yard or baking them in the oven. Prosaic work that was followed by the poetry of assemblage, of finding the right objects or images to convey the subtle, transient feelings – nostalgia, say, or joy – that Cornell experienced on his voyages through the city and which he logged in his voluminous and ardent diary (itself a collage composed of scribbled notes on napkins, paper bags and ticket stubs).

The boxes came first one by one, and then in sets or families. Works from the Medici Slot Machine series are melancholy marvels in which composed princesses and slouching princes gaze sorrowfully from simulacra of vending machines, that offer but do not relinquish a child’s treasury of jacks, compasses and coloured balls. In the Aviary series, lithographs of parrots cut from books and perched in cages are decorated with watch-faces or arranged as if for a shooting gallery. Or Hotels and Observatories: celestial lodging places for travellers passing between worlds.

Cornell found it agonising to sell these precious objects, frequently changing galleries and dealers so that no one person had too much control over his work. What he preferred was to give them away, especially to women. Cornell adored women. A deeply romantic man, he was cripplingly physically reserved, not helped by a jealous mother who repeatedly told him sex was repulsive. He longed to touch, but looking and fantasising were safer and had their own deep satisfactions. His diaries are filled with accounts of the women and especially teenaged girls (teeners, he called them, or fées) who caught his eye in the city, entries that veer between sentimental, creepy and painfully innocent.

Mostly he didn’t make contact, and when he did – presenting a bouquet to a cinema checkout girl; mailing an owl box to Audrey Hepburn – he was often rebuffed or misunderstood. All the same, he built productive friendships with many women artists and writers, among them Lee Miller, Marianne Moore and Susan Sontag, who later told Deborah Solomon: “I certainly was not relaxed or comfortable in his presence, but why should I be? That’s hardly a complaint. He was a delicate, complicated person whose imagination worked in a very special way.”

The most fertile of his alliances was with Yayoi Kusama, the Japanese avant-garde artist famous for her all-encompassing use of dots. They met in 1962, when Kusama was in her early 30s. According to her autobiography, Infinity Net, their relationship was erotic and creative, though his mother did her best to quash it, once throwing a bucket of water over them as they sat kissing beneath the backyard quince tree. In the end, Kusama withdrew, exhausted by the claustrophobic intensity of Cornell’s claims on her attention; the phone monologues that could go on for hours; the dozens of love notes that appeared in her mailbox daily.

As Cornell’s reputation grew, his production of boxes slowed. Instead, he returned to the two mediums with which he’d begun: collages and movie-making. In his late films, which he began in the mid-50s, he no longer used found footage but employed professional collaborators to record material at his command, which he then edited. There’s no better way of experiencing how he saw the world than by watching these celluloid records of his wandering, wondering gaze.

Take the ravishing Nymphlight, made in 1957 with the experimental filmmaker Rudy Burckhardt. A 12-year-old ballet dancer roams Bryant Park, the tree-lined square next to the New York Public Library. The camera’s eye is perpetually distracted by small movements, by quickenings and quiverings: a flock of pigeons performing their aerial ballet; water gushing from a fountain; wind in leaves.

Halfway through, it becomes enraptured by a succession of people, among them a woman with a dog – an elderly vagrant, who gazes back impassively – and a trash-collector. It’s hard to think of another artist who might have looked with such loving, serious attention at someone collecting garbage. What Nymphlight demonstrates is the radical equanimity of Cornell’s vision, his capacity for finding beauty in the most unprepossessing of physical forms.

The last years were the hardest. In 1965, Robert died of pneumonia, and the following year Cornell’s mother also died. In 1967, he was the subject of two big retrospectives, at the Pasadena Art Museum and the Guggenheim, as well as a lengthy profile in Life magazine. An ecstatic culmination of a life’s work, one might think, assuming that what was being angled for was fame. But this had never been Cornell’s interest or his aim.

Alone in the house on Utopia Parkway, he was ravaged by loneliness, and particularly by a longing for the physical contact he’d never really managed to attain. He hired assistants, mostly art students, to cook for him and help organise his work. He was visited by many devoted friends, but there still seemed to be something that kept him apart from other people: a pane of glass he couldn’t quite break open or undo. And yet he never lost his ability to look and be moved – bowled over, even – by the things he saw, from birds in a tree (“cheery-upping of insistent Robin”), or shifts in the weather, to the marvellous traffic of his dreams and visions.

“Gratitude, acknowledgement & remembrance for something that can so easily get lost”, he wrote in his diary on 27 December 1972, two days before he died of heart failure, inadvertently summing up the abiding genius of his own work. Then, perhaps glancing up at the window, he added his final words: “Sunshine breaking through going on 12 noon” – a last record of his long romance with what he once called the elated world.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion