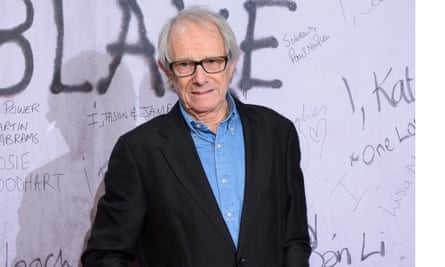

What kind of person are you if you aren’t angry, devastated, furious, howling when you leave the cinema after seeing Ken Loach’s Palme D’Or winning film, I, Daniel Blake?

If you aren’t angry that Stephanie Bottrill deliberately walked in front of an articulated lorry on the M6, after her benefits were sanctioned, what kind of person are you?

If you aren’t angry that Linda Wootton died within weeks of being assessed fit for work, as her letters from the Department of Work and Pensions were delivered to her hospital bed, what kind of person are you?

The “scroungers and skivers” rhetoric runs deep, a poison, an othering, a policy of fear. Mick Philpott – who caused the deaths of six of his children by arson in 2012 – is plastered across the front page of newspapers not as a murderer, but as a “benefit claimant”, and thus every man and woman in the dole queue is tarred as a potential murderer, waiting to snap.

I have lived these lives. Crashing from £27,000-a-year in a public service job to piles of brown envelopes, refusing to answer the door, turning off the fridge and unscrewing the light bulbs. I was Daniel Blake. I was his friend, Katie Morgan.

My story has been told to a Conservative party conference event so packed in 2013 that the doors were propped open and delegates stood in the corridor. A standing ovation, a patronising pat for my “bravery”, but a sociopathic disconnect between the votes they cast and the nights my son and I went to bed hungry.

My pleas for help – not for me – but for the millions tangled in this web disguised as a safety net, led to an unlikely friendship with Baroness Jenkin, the Tory peer who takes the Live Below The Line challenge every year to raise money for people going hungry. Along with Labour MP Frank Field, she set up the Feeding Britain inquiry into hunger and food bank use. They made dozens of recommendations to the government to tackle hunger at its root cause, but two years on, many of them have fallen on deaf ears.

Not all Tories are atrocious heartless fiends, I concede. But those who wield hunger as a weapon while claiming their own meals on expenses, are beyond satire. If you aren’t angry that 400,000 children rely on an extra tin dropped in a (rapidly disappearing) supermarket collection point to avoid going hungry, while the taxpayer foots the bill for Iain Duncan Smith’s £39 breakfast, then what kind of person are you?

Austerity is, devastatingly, not a party political issue. Not any more. A handful of MPs stand against it, drowned out by the insistence of the fiscally conservative – of all stripes – that a little belt-tightening is good for us. Even if those belts are tightened around the necks of the desperate, swinging from the rafters, starved, broken and left for dead.

I took a call as a trainee journalist at the Southend Echo in summer 2013. A quiet man, someone I knew from my time at the food bank, hanged himself after his benefits were sanctioned for the second time. His crime? He attended a hospital appointment.

Yet still the deniers will shake their heads, sceptical. It’s just a story, they say. Just a film. It’s not real. It fucking is real. I carry the scars deep in my heart, from my own stories, and for lost friends, five years on. I’m not sure if I will ever truly recover.

Food is a weapon in austerity Britain. Hunger, the threat of and the reality of, is used to coerce and control. That sentence alone feels paranoid, more than a smack of the mad conspiracy theorist, until you start to look harder. Half of food bank users are there as a direct result of benefit sanctions. Benefit sanctions have been applied in cases where a person has failed to turn up to the jobcentre because they are in hospital following a heart attack. A woman was sanctioned for attending cancer treatment. A man was sanctioned for attending a funeral.

Comply or starve. Comply and die, such were the cases, over a two-year period, of 2,400 people who died after their claim for employment and support allowance ended because they were declared “fit to work” by DWP. I wrote in 2013 that my three-year-old could pass an Atos assessment. It doesn’t mean I should have sent him to stack shelves in a supermarket.

I went to see the press screening of I, Daniel Blake in early September. I sat in a roomful of journalists as the two central characters lit tealights in a tray, under flowerpots, to take the chill off a room left freezing by shoddy windows and cut-off utilities, as I did and wrote about back in 2013.

I sat and watched with a heavy heart as she stole sanitary products from the supermarket, remembering going without, or folding up a clean sock, or balling up toilet tissue on the heaviest days. I barely left the house anyway, so there was nobody to really notice.

I sat and watched as she stole food. As she queued for the first time around the block at a food bank. As she gorged cold baked beans from a can with her fingers, having not eaten a thing for days. The young boy turning to his mother, asking her where her dinner was. She replies that she isn’t hungry, but she wasn’t hungry the night before, or the night before that, and soon he’ll realise that Mummy just isn’t hungry any more.

The woman beside me, a stranger, squeezed my forearm as I choked on guttural, involuntary sobs. I’m sorry, I whispered, sloping out to punch a wall in the corridor and cry into the blinding, unaware streets of west London. I looked mad. I am mad.

How can anyone sleep at night, knowing what we know? How does the world turn, and children going hungry to bed is a guilt alleviated by a sympathetic nod towards the cardboard food collection box in the supermarket? If you’re not angry, as Loach said, what kind of person are you?

I returned to watch the film as Daniel and Katie went into every available workplace within reasonable walking distance, to ask them if they had any jobs available. “No,” they would say, and the “not for you” would hang thick, and unsaid.

Oh, how I rage against the vulgarities of the alleged targeted sanctions at the Department of Work and Pensions. How eerily similar every whistleblower’s story is – bought for a meagre sum for the Jeremy Kyle Show, to josh at, for a moment of moral superiority, disguised as entertainment. But how infrequently we are invited to genuinely tell our stories. Trashy chat-show sofas are all we can aspire to, not BBC news chairs. Those of us lucky enough to find a platform are torn to pieces, commentators desperate to find some mud to sling, to reassure themselves that the working classes are a subspecies to be trampled out and kept in their places.

On Twitter, a woman going by the name of Kayceeee accused me of being self-pitying. “You have to make this all about you,” she wrote. Alan England, the chair of the English Democrats, said my retelling of this story was “boring” him. I will retell this until I no longer have to. Every party conference. Several speeches in parliament. To activists and policymakers and peers and whoever I have to spell it out to make the difference that is so desperately needed. I often leave conference halls unapologetic for the tears and anger that follow me. I hope you are furious, I close with, I hope you are devastated, and I hope you leave here and do fucking anything to help.

I responded to Kayceee and Alan with the movie trailer, where I stood in full technicolour, alongside Mhairi Black, Jeremy Corbyn, food bank users, DWP clients, well known faces and untold stories, each of us reciting the not-yet-famous-enough speech from the film. “I am Daniel Blake.” “I am Daniel Blake.” “I am Daniel Blake.” “I am Daniel Blake.”

I am Daniel Blake.

I am Katie Morgan.

But this is not my story alone.

Loach and the film’s screenwriter, Paul Laverty, travelled the country, meeting people, listening to stories, taking notes, visiting food banks. The extras in the heart-wrecking scene in the food bank were genuine clients, paid for their time in Morrisons food vouchers, presumably to meet an immediate need, and so as not to jeopardise their already fucked benefits.

A peek below the line at the comments section reveals the same old tropes. Food banks prop up junkies, one man claimed again and again and again on the official movie Facebook page. Dozens of us answered him with our testimonies, to be met with abuse about our appearance, judgments about our hastily bashed out spelling errors. There are none so blind as those that won’t see.

Daniel Blake and Katie Morgan are fictional characters, but their stories are devastatingly familiar. Open the Real Britain column by Ros Wynne-Jones in the Daily Mirror every week. Read my own blog, from 2011 to 2013, about benefit delays and suspensions and the devastating impact that has on just one life. Multiply it by a million, to the number of food bank boxes given out by the Trussell Trust alone in a single six-month period. Triple that, to include independent food banks. And if your compassion and understanding will allow it, multiply that by so many more, for those beneath the radar, who do not visit their doctor or have a social worker to direct them to charitable food, for fear of drawing attention to themselves and their situation.

I, Daniel Blake is not quite my life story. But yet, it is. I turned down the movie rights for my rags-to-book deal story in 2014, because I’m the lucky one. I felt the Hollywood treatment for “poor girl has hard time then it all gets better” would be an insult to the millions who don’t get to write about it in the Guardian afterwards. Don’t tell me to check my privilege, I know it. I found a job as a local journalist through sitting at council meetings and waiting for a vacancy to come up, after applying for hundreds of others. The rest is history – and 90-hour working weeks to stay afloat. I am currently writing this at 4am, having started work at 7. Five years after falling down the benefits rabbit hole, I’ve almost repaid the bank charges and court orders from that energy bill and others besides.

But Stephen Bottrill will never have his mother back.

Colin Wootton will never have his wife back.

My son has a mother on a cocktail of medication, therapy and a refusal to answer the front door half the time.

As Noam Chomsky said: “As long as the general population is passive, apathetic, diverted to consumerism or hatred of the vulnerable, then the powerful can do as they please, and those who survive will be left to contemplate the outcome.”

If you do one thing this week, go and see this film. Watch it and believe it, and get angry, and do something – anything – because there are millions of us, and this is our story. We are all Daniel Blake.

Comments for this piece will be pre-moderated prior to publication.