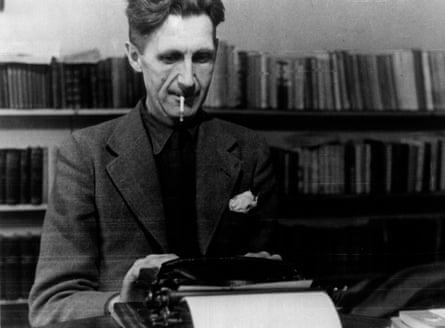

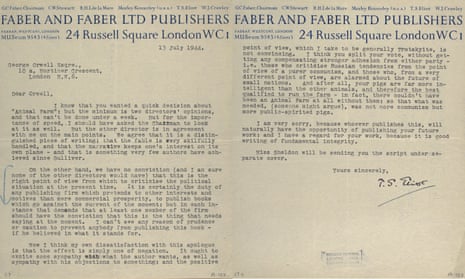

The letter in which TS Eliot rejects George Orwell’s allegory Animal Farm because “we have no conviction … that this is the right point of view from which to criticise the political situation” has been published online for the first time by the British Library, alongside a wealth of other material from 20th-century writers.

Addressing the author as “Dear Orwell”, Eliot, then a director at publishing firm Faber & Faber, writes on 13 July 1944 that the publisher will not be acquiring Animal Farm for publication. Eliot described its strengths: “We agree that it is a distinguished piece of writing; that the fable is very skilfully handled, and that the narrative keeps one’s interest on its own plane – and that is something very few authors have achieved since Gulliver.”

Animal Farm, a beast fable that satirised Stalinism and depicted Stalin as a traitor, was rejected by at least four publishers, with many, like Eliot, feeling it was too controversial at a time when Britain was allied with the Soviet Union against Germany.

“I think my own dissatisfaction with this apologue is that the effect is simply one of negation. It ought to excite some sympathy with what the author wants, as well as sympathy with his objections to something: and the positive point of view, which I take to be generally Trotskyite, is not convincing,” wrote Eliot to Orwell. “And after all, your pigs are far more intelligent than the other animals, and therefore the best qualified to run the farm – in fact, there couldn’t have been an Animal Farm at all without them: so that what was needed (someone might argue), was not more communism but more public-spirited pigs.”

Animal Farm went on to be published by Secker & Warburg in August 1945. In a preface by Orwell, not printed until 1972, the author says that when he wrote the book, in 1943: “It was obvious that there would be great difficulty in getting it published.”

“If publishers and editors exert themselves to keep certain topics out of print, it is not because they are frightened of prosecution, but because they are frightened of public opinion. In this country intellectual cowardice is the worst enemy a writer or journalist has to face, and that fact does not seem to me to have had the discussion it deserves,” wrote Orwell.

“At this moment what is demanded by the prevailing orthodoxy is an uncritical admiration of Soviet Russia. Everyone knows this, nearly everyone acts on it. Any serious criticism of the Soviet regime, any disclosure of facts which the Soviet government would prefer to keep hidden, is next door to unprintable.”

Eliot’s letter is one of more than 300 items which have been digitised by the British Library, a mixture of drafts, diaries, letters and notebooks by authors ranging from Virginia Woolf to Angela Carter and Ted Hughes. The literary archive reveals that Orwell was not the only major writer to suffer a series of rejections: the British Library has also digitised a host of rejections for James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, showing how his patron Harriet Shaw Weaver attempted to find a printer for the novel she had published in serialised form in The Egoist.

Weaver was told by one printer that “we would not knowingly undertake any work of a doubtful character even though it may be a classic”, while another asks Weaver, addressed as “Dear Sir”, to “exclude some of the paragraphs which others have taken exception to” if they are to print it. British law meant that a printer rather than a publisher would be held responsible if a book was found objectionable, but US publisher BW Huebsch eventually agreed to print Joyce’s Portrait.

The archive also contains a 1918 letter from Woolf, declining to print Ulysses. Woolf tells Weaver that “the length is an insuperable difficulty to us”, because “we can get no one to help us, and at our rate of progress a book of 300 pages would take at least two years to produce – which is, of course, out of the question for you or Mr Joyce”.

“Until now these treasures could only be viewed in the British Library reading rooms or on display in exhibitions – now Discovering Literature: 20th Century will bring these items to anyone in the world with an internet connection,” said Anna Lobbenberg, digital programmes manager at the British Library.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion