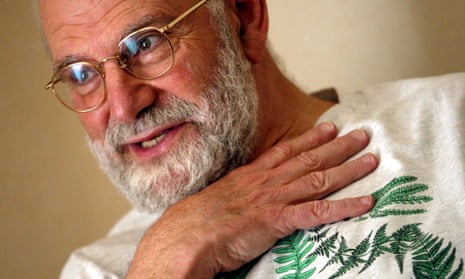

The world will be a far, far poorer place without regular reports from the distant reaches of the land of mind and brain by the great neurologist Oliver Sacks. He had a unique literary gift. A clinician of compassion, he could also – in a deft, often passionate portrait – familiarise us with human peculiarities and the kinds of talents and courage they can give rise to.

Where Balzac’s Human Comedy is filled with insights into the struggles of the youth from the provinces in the corrupt capital, or of the far too pleasure-loving young poet, Sacks’s human comedy presents the tragic case of the musician Dr P who develops visual agnosia and fails to recognise ordinary objects, in the process mistaking his wife for a hat; or the “extinct volcanoes” of Awakenings, people frozen by the encephalitis epidemic of the 1920s and only woken in 1969 by Sacks’s administration of the drug L-Dopa; or the tics and passions of a Tourette’s syndrome patient; or the world of the deaf who can “see” voices; or the autistic boy who is a draftsman of genius. Sacks’s clinical tales are the quintessential literature for our medicalised times.

Inspired by that other great neurologist Sigmund Freud and his case histories and autobiographical book on dreams, as well as the “neurographies” of the Russian psychologist Alexander Luria, Sacks was also an inveterate keeper of journals and a brilliant memoirist. In A Leg to Stand On, published in 1984, he becomes his own patient and the hero of his own “neurological novella”. An accident on a mountain in Norway, which wounded the muscles and nerves of his leg, led to a series of singular effects: a “sort of paralysis or alienation of the leg, reducing it to an object which seemed unrelated to me”. The re-integration of the leg into Sacks becomes a journey into selfhood.

Uncle Tungsten, his memories of a chemical boyhood and the bodies brought home for dissection by his surgeon mother, is no less brilliant. In his wonderful book on the many kinds of hallucination humans experience, his own early days on amphetamines and their horrific hallucinatory effects are drawn on.

In his most recent memoir, On the Move, he writes of his schizophrenic brother, who is perhaps the source of Sacks’s profoundly humane engagement with the extraordinary. It may very well have been his imaginative abilities that for a while made Sacks a little suspect in the drier spheres of science. But Sacks’s aim, as he noted in an interview in 1991, when the film based on Awakenings came out, was ever less to tread the strict path of exact fact than to show the “fundamental dramatic truth of the experience with all its wonder and despair … That there is still the potential of an intense inner life and individuality even in people who seem so very damaged”.

Sacks showed us that in trumps. He will be very much missed.