Is Lindsey Graham Backing a 'Race-Baiting, Xenophobic Religious Bigot'?

If Trump’s most voluble critic in the Senate may be coming around, will any Republican politicians hold the line against endorsing their nominee?

The Republican Party’s slow rally around Donald Trump is no surprise. Parties almost always unify—at least to some degree—around their nominees. Movements like conservatism are built on ideologies, but political parties are above all built to win. Trump is already seeing the fruits of consolidation. Democrats remain divided, but with the GOP field cleared, Trump has opened up a lead in the RealClearPolitics polling average against Hillary Clinton. The margin is tiny—just 0.2 percent—and it’s early yet, so the lead says more about Trump’s success in unifying his party than his likelihood of prevailing in November.

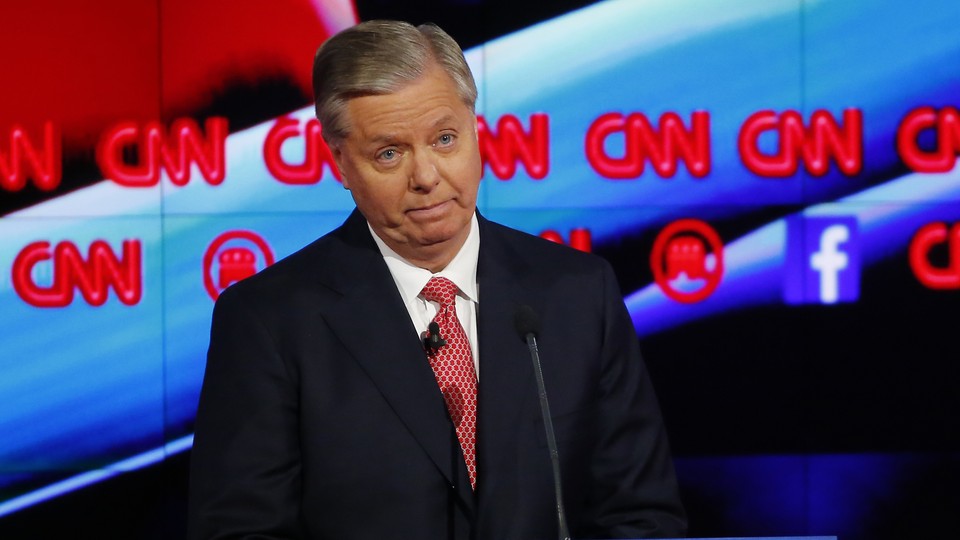

The way unification is happening, however, and the people involved, do offer some surprises. Most prominently, Senator Lindsey Graham reportedly urged Florida Republicans at a fundraiser on Saturday to back Trump. The South Carolinian’s spokesman wouldn’t confirm the specific remarks, but he also didn’t deny them, noting that Graham (no relation to this author) has been clear that he does not support a third-party alternative. “There hasn't been any change in his position,” spokesman Kevin Bishop told CNN. “He's been pretty upfront and outspoken.”

That may be strictly true, but it downplays the magnitude of Graham backing Trump—even if he only does so privately. (One attendee at the fundraiser told CNN that Graham was declining to endorse Trump publicly because he didn’t think it would help the entertainer.) It’s not just that Graham disagrees with Trump on nearly every issue that comes to mind, from foreign policy to immigration. This is Lindsey Graham, whose private cellphone number Trump released publicly in July 2015, in an act of intense bullying that at the time seemed like an oddity but has come to be Trump’s trademark.

Lindsey Graham, who in December asked, “You know how you make America great again? Tell Donald Trump to go to hell,” and continued, “He's a race-baiting, xenophobic, religious bigot. He doesn't represent my party. He doesn't represent the values that the men and women who wear the uniform are fighting for .... He's the ISIL man of the year.”

Lindsey Graham, who in March said Trump should have been expelled from the Republican Party.

Graham hated both Trump and Ted Cruz so much that he once likened the contest between the two of them to a choice between being shot and poisoned. As a result, it was a major milestone in the Republican establishment’s drive to stop Trump this spring when even Graham—who had quipped, “If you kill Ted Cruz on the floor of the Senate, and the trial was in the Senate, nobody could convict you”—endorsed Cruz.

Graham still didn’t love his Texas colleague, as a hilarious Daily Show appearance demonstrated, but he was willing to back him because he hated Trump so much more. Pressed by Trevor Noah on why he was backing Cruz, Graham offered that “he’s not completely crazy” and “that he’s not Trump.”

“If Donald Trump carries the banner of my party, I think it taints conservatism for generations to come,” Graham added. “I think his campaign is opportunistic, race-baiting, religious bigotry, xenophobia … other than that he’d be a good nominee.”

In early May, Graham said that Trump’s foreign policy would lead to another 9/11. And he told CNN that he couldn’t vote for either Trump or Clinton.

Yet Graham has now decided that maybe Trump is good enough after all. The reported switch doesn’t come from a vacuum. Since Trump locked up the GOP nomination, he has begun reaching out to some top Republicans, and the two men had what Graham called a “cordial, pleasant” phone call about foreign policy.

But if Lindsey Graham of all people can come around to Donald Trump, what Republican can’t? Increasingly, it seems that the only figures of any profile who aren’t backing Trump are an increasingly embattled group of staunchly principled conservative journalists and pundits. It’s harder and harder to find elected or appointed party figureheads who stand with them—though a few, like Ted Cruz and the Bushes, who have remained silent for now.

The other notable Trump endorsement over the weekend came from Foster Friess, the conservative megadonor who came to national prominence during the 2012 GOP primary—backing Rick Santorum over the less socially conservative and overall more moderate Mitt Romney. Now Friess has decided to support Trump, who is far more socially moderate than Romney was, and hardly an orthodox conservative on a range of other issues.

The way Friess justified his endorsement is peculiar. “My success came from harnessing people’s strengths and ignoring their weaknesses,” Friess wrote in an email to The Hill. “And also, from assessing people not according to their pasts or where they are today, but rather based on what they can become.” In other words, Friess is saying that Donald Trump cannot be judged on what he has said or done—either in the past or in the present. That analysis is either oracular or delusional. It implies that Trump will either betray the supporters who have brought him this far or else disappoint the new ones like Friess who are sure he can change.

The reason Republicans are coming around to Trump is simple enough: When it comes down to an election between Trump and Hillary Clinton, they’d rather win with a deeply flawed Republican than lose to the Democrat. Their begrudging statements come with the strained vivacity of hostages making videos in which they praise their treatment at the hands of their captors. That’s not a bad metaphor: Trump has effectively kidnapped the Republican Party, and now its stalwarts are in the awkward position of either backing the kidnapper or risking serious harm to the party. The worst part is they know that even if they back Trump, he could lose the general election and fatally wound the party anyway.

Many Republicans, especially conservative ones, feel that the GOP has lost its way in recent elections, prizing winning over upholding conservative principles and as a result getting neither, as with Mitt Romney’s defeat in 2012. They accuse Republican leaders of being craven careerists, a charge that Trump’s supporters have adopted. For a few months in 2015 and 2016, Trump’s ascendance seemed to be a real clarion call to principle for many establishment Republicans, a line in the sand that could not be crossed, especially given Trump’s rejection of many conservative ideas. Ironically, their belated acquiescence to Trump—surrendering principle in the name of electoral victory—might be the ultimate validation of their own critique.