If there are two words in the English language likely to trigger a curl of the lip, “slug mucus” would be towards the top of the list. But while the molluscs and their slimy secretions are the bane of the green-fingered, it seems they have triggered a moment of inspiration in the laboratory.

Researchers say they have developed tough, flexible glues designed to help patch up wounds, drawing on lessons learned from the creatures’ sticky goo.

While medical-grade glues are already available to help repair tissues, they are far from perfect. Issues include adhesives being weak, toxic to cells, unable to work well on wet surfaces and being rigid and brittle – a problem given the dynamic nature of biological tissues.

Now scientists say they have come up with an answer, developing strong glues that can work even on bloody, moving tissues and are compatible with cells.

“Basically we can solve all those issues associated with previous adhesives,” said Jianyu Li, first author of the research from Harvard University.

Writing in the journal Science, Li and colleagues reveal how they took inspiration from the sticky, elastic defensive mucus secreted by the common western European slug Arion subfuscus to foil predators.

With the mucus known to be made up of a tough substance containing positively-charged proteins, Li and colleagues set about developing their own version.

The upshot is a new family of adhesives, which feature positively-charged polymers within water-based gel materials, known as hydrogels. These positively-charged polymers form bonds with the hydrogel and the surface of the biological tissues to be glued, while the hydrogel itself not only acts as a matrix, but prevents the adhesive from cracking easily. “You can think of it as the shock-absorber like you’ve got in your car,” said Li.

Aided by another substance to boost bonding, the glues were found not only to stick to pig skin but also cartilage, heart, artery and liver tissues – with a strength greater than that of a range of currently available adhesives. Unlike the widely used medical superglues, or cyanoacrylates, they did not form strong bonds immediately, but instead showed a rapid increase in adhesion over time, a feature the team says will prove useful when it comes to handling and repositioning.

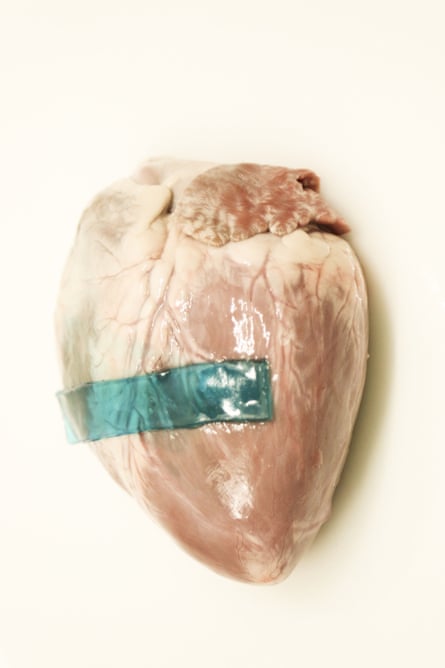

Among their tests, Li and colleagues also tried the new glues on a beating pig’s heart which was covered in blood, finding that the glues worked even on the wet, curved, moving surface while, when applied to liver tissue, one of the glues could be stretched to 14 times their initial length before malfunctioning.

In an injectable form, the glues were able to seal up a hole in a pig’s heart, with the seal intact after tens of thousands of cycles of inflation and deflation, while rat studies showed they could also be used to stop bleeding, without the side effects of some current alternatives. What’s more, the team say the glues were not found to be harmful or toxic to cells.

It may be a matter of years before the glues take hold but David Mooney, another author of the study - also from Harvard University, said the development of the new adhesives was exciting.

“It both demonstrates the properties of slug mucus can inspire the design of new adhesives, and these adhesives have greatly superior properties to the currently available medical adhesives,” he said.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion