“The ineffectiveness of journalists who peddle in truth has never been more apparent to me than in this election cycle.”

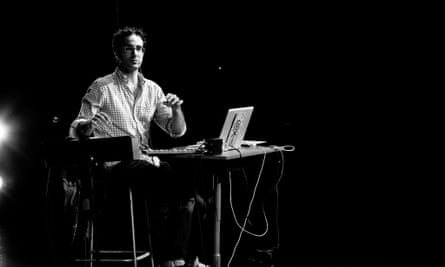

Jad Abumrad, the co-host and founder of the hit radio show and podcast Radiolab isn’t feeling too generous about the mainstream media when we speak.

“Journalists [in America] can write a thousand articles about whether what this person said was wrong or right, but no one here seems to give a shit,” he says.

“Like, it simply doesn’t make a dent any more – so what kind of journalism actually will matter? That’s a really important question, and for me the only answer I’ve got is it’s the kind of journalism that forces you to experience what someone else is going through.”

For Abumrad, that’s what Radiolab is trying to achieve. The show explores big ideas by following the stories of everyday people. It launched as a science program in 2002, but soon began tackling broader issues from different angles, including sport, the death penalty, counter-terrorism and the US supreme court. It’s now one of the most successful podcasts in the world, spawning a series of live shows and specialising in the kind of journalism Abumrad thinks is vital right now.

“There is like a fucking ocean of difference between explanation and experience and I feel what I’m always trying to do is cross the ocean – I’m trying to get to the experience,” he says.

Most of Radiolab is fast and fun, expertly wielding audio to help the listener really connect with an idea. Anchored by Abumrad and his co-host Robert Krulwich, it’s as if two smart people are having an interesting chat in a cafe – which is then augmented with layers of intricate soundscapes.

An August episode titled Playing God, for instance, culminates in the most harrowing audio I have ever heard. The audience is transported to Haiti after the 2010 earthquake where they meet doctors forced to choose who lives and dies when not everyone can be saved. A doctor lists his reasons for denying a woman oxygen: they are running out of the gas; she has a chronic condition; he could save other people who would have a better chance. It’s all very rational until you hear the sound of her struggling to breathe as she’s transferred to another hospital where she’s expected to die.

In a more cheery May episode, Bigger Than Bacon, they study a tiny shrimp that makes a bubble as hot as the sun in order to stun its prey. The audience is taken from hearing the sounds it makes just above the water to experiencing what happens inside the shrimp’s claw when it snaps together. The water rushes, bubbles and implodes around you, and you feel as if you are right there, at the microscopic level, as it happens. Radiolab can make you see things just by hearing them.

“It’s about taking these sort of beautiful abstractions, and making them feel like they have blood and guts and flesh,” Abumrad says. “It’s about making them hit you – you want the information to just collide with someone.”

As Radiolab evolves, Abumrad hopes to launch new projects with the same aesthetics – such as the recent series on the US supreme court called More Perfect.

“I’m interested to see where we can expand this thing, and if it can go from being a show to being an ecosystem – like a terrain where lots of little fiefdoms all live in the world called Radiolab, but are actually a bunch of separate projects. I sort of see that as our future, something closer to a network.”

The last few years of the podcasting boom have seen likeminded networks – including Gimlet and Panoply – dishing out amazing content funded by advertisers, subscribers and clients. But the future of the industry worries Abumrad.

“It seems like there’s a big economy out there for the first time, which is a big fucking deal ... But I’m pretty sure supply is outstripping demand right now,” he says. “I can’t say for sure but that’s just my gut.

“There’s a lot of podcasts all of a sudden, and some of them are amazing, so as a creative person I’m rooting for them all – but there’s a lot of them and they’re all broadcasting the same ads, so I’m not sure that the pool of ad money there is enough to drive it all. So I do worry that we are in some kind of bubble.”

There may be some problems looming but Abumrad is hopeful for the long-term prospects.

“I’m not going to predict, but let me give you my aspirations. What I hope happens is that this becomes a little like TV: we start to get the diversity of content that you see on TV, where you’ve got long narrative stuff but you’ve also got stupid short stuff, you’ve got comedy, you’ve got drama, you’ve got violent drama, bloody stuff like that zombie thing – but you also have public affairs stuff,” he says.

“I hope more than anything that we start to treat our business like film treat their business. Film has film school and production school where people can go to learn how to do it ... there are journalism schools but they are all closing.

“[Podcasting school] doesn’t exist, there’s no place someone can go except to get a job where they can learn that stuff.”

At the end of the day, he says, Radiolab and This American Life are just trying to deliver good journalism.

“Forget the style, you’re actually trying to deliver news; you’re trying to figure out what’s happening in the world and make sense of it.”