The Other Devil's Bargain

The Republican majorities in Congress gambled they could ignore Trump's misdeeds, and still get him to sign their bills—but it’s not working out as they expected.

Devil’s Bargain is the title of the best-selling book by Joshua Green about the relationship between Donald Trump and Steve Bannon—a relationship, of course, newly altered. But the Trump-Bannon relationship is not the only, or even the most important, devil’s bargain surrounding Trump—that distinction goes to the odd, strained, and curious relationship between Trump and Republicans in Congress.

It is no secret that the overwhelming majority of Republicans in the House and Senate did not want Trump to be their party’s nominee—he had the fewest endorsements from his party’s members of Congress before the race was settled than any nominee in modern memory. And a large number of GOP legislators were privately appalled as the general election campaign went on. When the Access Hollywood tape emerged, private unease became more public—one of the most vivid examples was Representative Jason Chaffetz of Utah, who told a Utah television station, “I can no longer in good conscience endorse this person for president. It is some of the most abhorrent and offensive comments that you can possibly imagine. My wife and I, we have a 15-year-old daughter, and if I can’t look her in the eye and tell her these things, I can’t endorse this person.”

But only 19 days later, as the election approached, Chaffetz took a different tack—saying while he would not endorse Trump, he would vote for him. And after Trump won the election, Chaffetz, the chair of the key House oversight committee, became one of Trump’s most enthusiastic cheerleaders, making clear that he would not look at Trump’s transgressions and violations of the Constitution’s Emoluments clauses, but still wanted to keep the focus on Hillary Clinton’s emails.

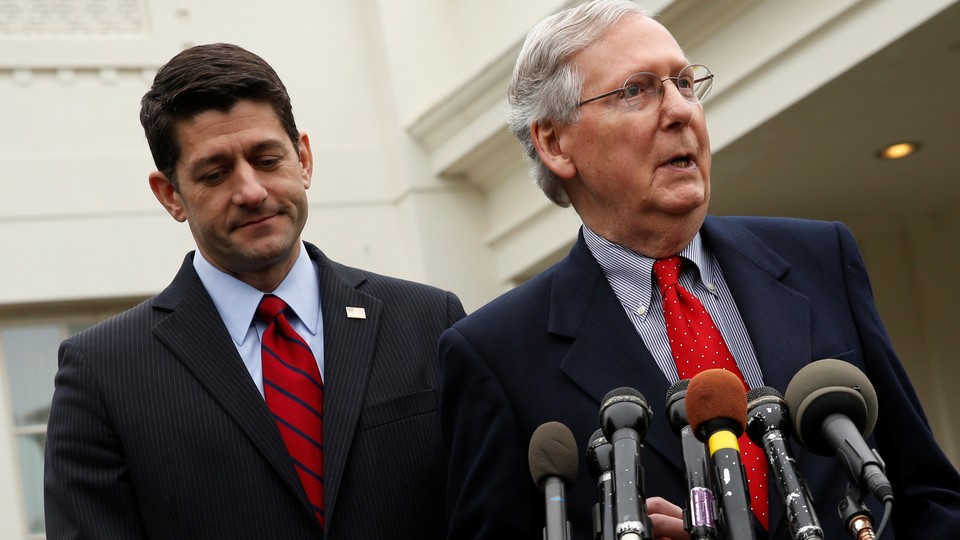

A similar phenomenon hit Speaker of the House Paul Ryan, who in a conference call with his members after the tape said, “His comments are not anywhere in keeping with our party’s principles and values. There are basically two things that I want to make really clear, as for myself as your speaker. I am not going to defend Donald Trump—not now, not in the future. As you probably heard, I disinvited him from my first congressional district GOP event this weekend—a thing I do every year. And I’m not going to be campaigning with him over the next 30 days.”

Trump campaign advisor Steve Bannon subsequently called Ryan “the enemy,” and the speaker suffered repeated barbs tossed his way by Trump. But since the election, Ryan has gone through multiple contortions to explain away Trump’s misbehavior and avoid direct criticism of the president, even as he has at times criticized indirectly Trump’s comments, behavior, and tweets. And the same holds for all but a handful of Republicans in the House and Senate, doing everything they can to avoid hitting the president and providing little in the way of checks and balances on things like Russian interference in the election and Trump’s kleptocratic behavior.

There are two reasons for this. One is that Republicans in Congress fear the backlash from taking on the president. Trump has shown that he will not hesitate to hit back directly and personally at lawmakers who do so—and that in turn will resonate with the president’s ardent base. That base may only be 35 percent or so of the electorate, but it is 75 percent of Republican identifiers, concentrated among the most active primary and caucus voters—and these voters are also the base of support for Republican lawmakers.

But the fear is not just about incurring the wrath of activist voters. Taking on Trump also means taking on his media acolytes—Sean Hannity, Tucker Carlson, Fox & Friends, Breitbart, Rush Limbaugh, Alex Jones, Laura Ingraham, Mark Levin, and a bevy of bloggers who have their own independent power with conservatives. When Limbaugh, Levin, and Ingraham decided to target then-Majority Whip Eric Cantor, they precipitated his stunning primary defeat to Tea Party insurgent Dave Brat, a lesson that has not been lost on other Republican lawmakers, especially the leaders. And there is the all-important money factor, that billionaire Trump supporters like the Mercers might help finance primary challengers to the apostates.

The survival instinct is a powerful one, but the second reason for this devil’s bargain is more important, and more intriguing as we go forward. For Republicans in Congress, Trump’s election provided an unexpected and irresistible opportunity to achieve the radical policy goals that had eluded them for a decade or more—from ginormous tax cuts tilted to the superrich to a wholesale rewrite of health policy via repeal of Obamacare to the transformation of Medicare, Social Security, and Medicaid (along with deep cuts in the latter). And while Trump had run on a very different platform and set of goals—he decried big tax cuts for the rich, and pledged not to touch Social Security, Medicare, or Medicaid—the GOP members of Congress believed that this president would sign anything they managed to pass and put on his desk and claim a huge victory in the process.

While Republicans have exulted in the confirmation of Neil Gorsuch to the Supreme Court after they managed to block Merrick Garland, the rest of the agenda has not worked the way they wanted or expected. One major snag has been their own failure to get that ambitious agenda through one or both houses of Congress. The typical differences in style, norms, rules, timelines, and priorities between the House and Senate are one part of the problem. But the inability of Ryan, Senate Majority Leader McConnell, and others to move from vague and broad “principles” to workable solutions that meet the needs of both radical Freedom Caucus lawmakers and the more pragmatic conservatives, combined with the insistence on relying only on Republican votes with narrow majorities in both houses, has created one blockage and embarrassment after another.

Trump, of course, has not helped in the way a standard president would—bringing lawmakers along, participating in logrolling and horse-trading, using his own expertise to find the right formulas. Trump’s tone-deafness to politics and Congress, his complete lack of knowledge of major policy areas, and his narcissism have made the tasks of Ryan and McConnell more difficult, not less. The classic example: After leading a victory celebration at the White House, spiking the proverbial football when an Obamacare-repeal bill passed the House, the president subsequently told Republican senators that the bill he had extolled was “mean,” then held an embarrassing session with those senators in which he threatened one (Dean Heller of Nevada) with the loss of his seat and showed no understanding at all of the issues at stake in the various alternatives. Trump also demanded passage of the big tax-reform proposal by September, demonstrating ignorance both of the need to pass a new budget resolution before tax reform can be considered, the time required to craft a reform package, and the demands of pressing deadline decisions that will dominate the fall.

At the top of the September agenda: Republicans in Congress face both a showdown over the debt ceiling and a possible shutdown of parts of the government over deep disagreements in their own ranks on spending numbers and priorities. On the debt ceiling, instead of providing leadership or cover for congressional Republicans, the Trump team has been deeply divided, with Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin pleading for a simple, straightforward, clean debt-ceiling increase, while OMB Director Mick Mulvaney first called for using the debt ceiling for leverage to get much deeper spending cuts, then said reluctantly that he could support a straight increase, but made clear he saw no real downside to a breach. Trump, after saying during the campaign that debt renegotiation and bankruptcy can be good things, has been AWOL on the debt-ceiling negotiations.

Now, of course, the dynamic has become much more complicated and treacherous, as the casual threat of attack on North Korea, the machinations and dysfunction inside the Trump White House, and the president’s stunning and defiant embrace in his press conference of white supremacists and anti-Semites, have made the fate of must-pass legislation more dicey. Most Republicans have been forced to spend immense time and energy defending the indefensible or attacking it while not directly criticizing the president, and at the same time coping with their party’s stained image. A dysfunctional, defiant, scandal-plagued president may actually preclude success at passing any core conservative policy priorities, and a narcissist in the White House, stung by the lack of celebratory Rose Garden signing ceremonies, or by the turmoil that will accompany default or shutdown, might then blame his own partisans for the failures.

All of a sudden, a devil’s bargain becomes a devilish disaster. And if that happens, look for more and more congressional Republicans to seek a way out, to find a path to avoid full scale revolt at the grass roots while still ending up with a more pleasant and pliant President Pence.