To the Media, 'Black' Is Too Often Shorthand for 'Poor'

Presenting American poverty as monochrome isn't just inaccurate—it reinforces the widespread belief that skin color has something to do with industriousness.

What does poverty look like in America?

Judging by how it's portrayed in the media, it looks black.

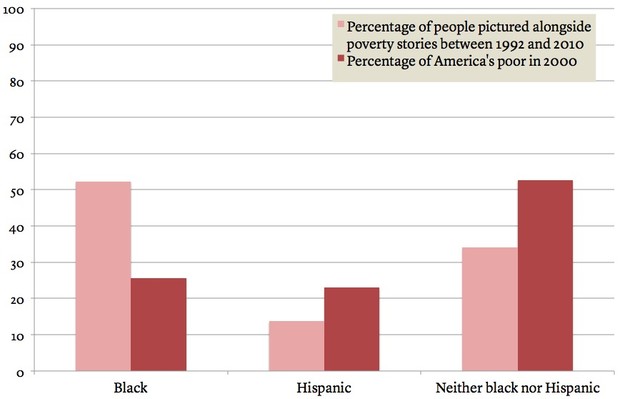

That's the conclusion of a new study by Bas W. van Doorn, a professor of political science at the College of Wooster, in Ohio, which examined 474 stories about poverty published in Time, Newsweek, and U.S. News and World Report between 1992 and 2010. In the images that ran alongside those stories in print, black people were overrepresented, appearing in a little more than half of the images, even though they made up only a quarter of people below the poverty line during that time span. Hispanic people, who account for 23 percent of America's poor, were significantly under-represented in the images, appearing in 13.7 percent of them.

Note: Poverty stories were from Time, Newsweek, and U.S. News and World Report | Data: van Doorn

Those discrepancies are striking, and, as van Doorn points out, sadly predictable, neatly mirroring the stereotypes of Americans more generally. In 1991, a survey found that Americans’ median guess at how many of the country’s poor people were black was 50 percent, though at the time the actual figure was 29 percent. Ten years later, another poll found that 41 percent of respondents overestimated the percentage by at least a factor of two. (In 2013, 23.5 percent of America’s poor were black.)

But it's not just that poor people are imagined to be black—they're also commonly thought of as lazy. In 2008, only 37.6 percent of Americans considered black people hardworking, whereas 60.9 percent said the same of Hispanic people. For white people and Asian people, these percentages were 58.6 and 64.5, respectively. "To the extent that photo editors share these stereotypes," van Doorn writes, "it is no surprise that African Americans are over- and Hispanics are under-represented among the pictured poor."

One potential hole in van Doorn's study is that he analyzed weekly news magazines published in print, which makes sense when approaching the question for 1992, but made less sense by 2010. On top of that, Time and Newsweek's print staffs (likely a relatively old-school bunch) might not be reflective of today's entire media world. Still, some of the discrepancies between print publications' "pictured poor" and reality are so large—38 percent of welfare recipients are black, yet 80 percent of the people pictured alongside Newsweek's stories on welfare were black—that it's hard to imagine that digital publications would have shaken the habit entirely.

Van Doorn is interested in the relationships between the adjectives “poor,” “black,” and “lazy,” arguing in his paper that they must have something to do with why some Americans are opposed to generous welfare programs. A 1999 book that he leans on heavily, Why Americans Hate Welfare by Martin Gilens, made the case that supporting impoverished adults with cash payouts is unpopular because white voters see such efforts as primarily benefitting black people—whom they believe to be lazy and thus undeserving. If the media's portrayal of poverty were to reflect its actual diversity, perhaps voters would view social welfare programs more favorably. But that wouldn't change the underlying phenomenon: that many still believe skin color says something about work ethic.