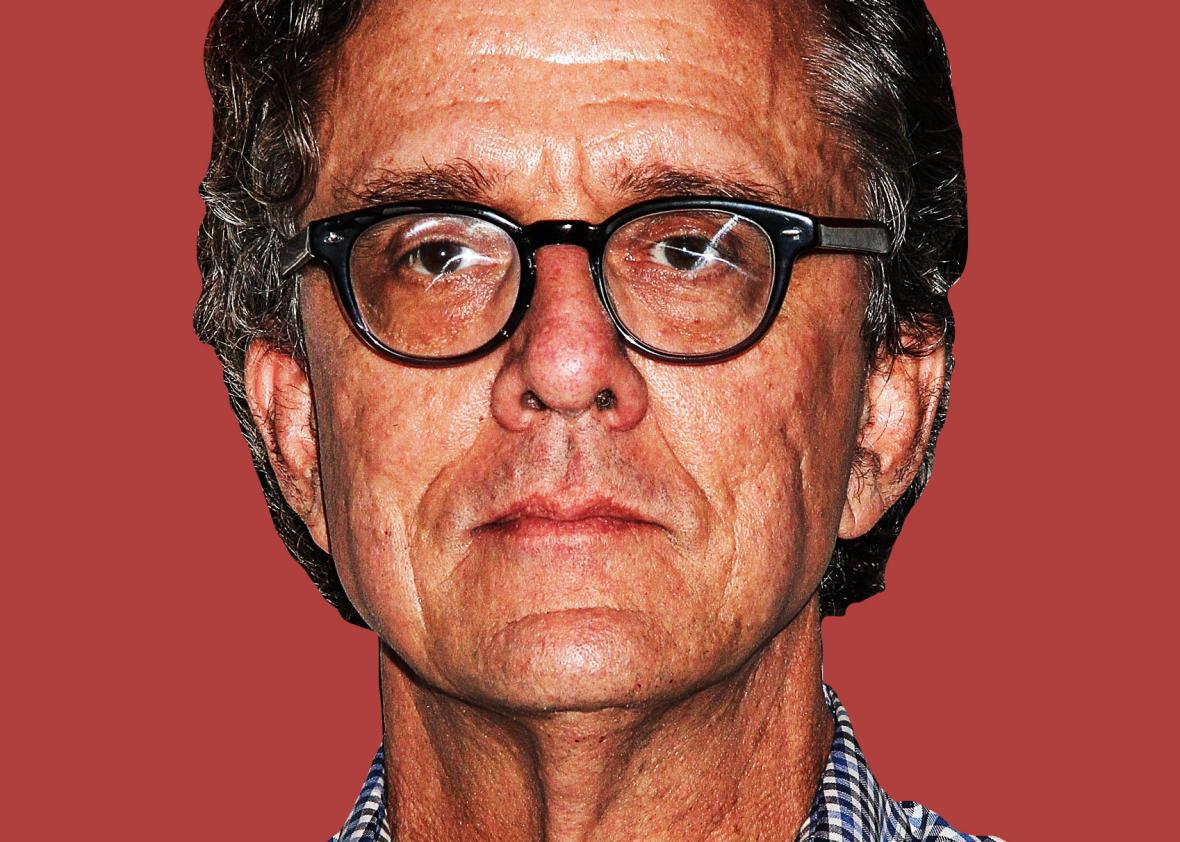

Kurt Andersen’s new book, Fantasyland: How America Went Haywire: A 500-Year History, tackles many of the themes he has written about over the course of his career, including how our politics is influenced by broader trends in American culture and society. Andersen, who hosts a radio show about culture, Studio 360, which recently joined the Slate podcast fold, and co-founded Spy magazine (which was known for, among other things, going after Donald Trump), connects our insane current moment to the timeless idea of American exceptionalism, a creed that he believes always contained a certain naiveté and gullibility. What’s worse, he argues, is that this idea became co-mingled with the individualism and selfishness of the 1960s—helping to birth Donald Trump and much more. (A long much-debated excerpt from Andersen’s book appears as the current cover story in the Atlantic.)

I spoke by phone with Andersen recently. During the course of our conversation, which has been edited and condensed for clarity, we discussed whether there is a connection between religious belief and conspiracy theories, whether America is crazier than anywhere else, and whether Donald Trump has changed over the past three decades.

Isaac Chotiner: Why has America gone insane?

Kurt Andersen: There are so many reasons. Some of the main strands I follow are extreme religiosity from the beginning, which has effloresced, especially in the last century and especially in the last few decades, into something extraordinary compared to anything else in the developed world.

Individualism is another way we went insane, when individualism got out of control, along with the 1960s, and along with the various forms of show business into which we can imagine ourselves and other beings.

Why do you think the ’60s are partially to blame for where we are right now?

Only partially. This excerpt of the book that appeared in the Atlantic this month, thats what they were interested in.

Well the excerpt’s like 400,000 words.

No, it’s only 380,000 words. I guess what I believe happened, among all the great things that happened in the ’60s, like civil rights and the beginning of women’s equality and the fun and everything else, was this new relativism, that’s the simplest word, that all forms of truth-finding are equally valid, whether scientific or magical. It became uncool and in some cases impermissible to say, “No, that’s fine if you want to believe that, but science is superior.”

That, in the general sense, began as a thing on the left, to which conservatives at the time were up in arms. One of the things that happened, of course, is that 50 years on, that kind of relativism and that kind of do your own thing, believe your own thing, and have your own truth has consequentially empowered forces and individuals on the right.

OK but what is the causal connection there? Because if it was some sort of causal connection between the relativism in the ’60s and the nightmare of our politics today, wouldn’t you expect it to impact the left more?

You would if history and culture worked in obvious and predictable ways, but they don’t. No, I don’t believe that Donald Trump read Foucault and thought, “My God, truth is all relative.”

I think we agree on that, yeah.

I do believe that as academic relativism and indeed as countercultural relativism grew in the ’60s, two separate but connected things, they so pervasively affected the way Americans think, that that was one thing—not the only thing, perhaps not even the main thing—that empowered and permitted the “whatever we want” place we are in today, and the, “Oh no, I don’t believe. I believe that there’s some conspiracy of journalists and scientists pretending that climate change is the result of human activities, and/or I believe that some other conspiracy is responsible for the fact that autism is caused by vaccines.” I don’t want to follow into the Donald Trumpian both sides are at fault. While there are people on the left who fall prey to impossible and implausible and dubious conspiracy theories and science-denying and all the rest, it is highly asymmetrical.

You are talking about people who believe things without reason. I’m trying to understand: Is there some data or something that you’re looking at that makes you think this is where this trend started, that people became more unreasonable in the ’60s?

There is data that I’ve looked at extensively and report in the book extensively about the false things that people believe compared to earlier times. No, there’s no data that supports my speculative cultural history, that part of how we got here—part, not all—is this general abdication by gatekeepers and the establishment in the academy and elsewhere who used to say, “No, this is much, much closer to the truth than this,” rather than at the beginning to say, “No, we’re not going to do that as much.” Is there data or survey research to say that that was part of the cause? No, it’s my opinion.

In your book you quote a bunch of survey data that’s alarming, like about people thinking Obama is the Antichrist, and you write, “Why are we like this? The short answer is because we’re Americans—because being American means we can believe anything we want; that our beliefs are equal or superior to anyone else’s, experts be damned. Once people commit to that approach, the world turns inside out, and no cause-and-effect connection is fixed. The credible becomes incredible and the incredible credible.”

The world is full of countries where there is strong religious belief and a strong belief in conspiracies. What is it specifically that you think is American about that rather than this is how human beings are, that we believe weird stuff?

The lines you just read, of course, are from the introductory chapter, so they are meant, just for the record, to be a high gloss that then I would spend 400 pages going into detail about.

I can read the whole book in this interview. We could do that.

Oh, stop. No, but in terms of just the religious stuff, there’s this massive set of survey data about how much more religious we are, more prayerful we are, than other developed countries. I’m not saying America is so different from Pakistan. I’m saying America is different from Canada and Japan and Europe and Australia and the rest of the developed world, and we are, by every measure of religiosity. Again, it’s not just believe in God or not. It’s the very detailed beliefs that we have as a people. That is just the clearest and starkest and most data-proven truth that we are different.

Tocqueville thought we were different than the French 170 years ago, but we have gotten more different. As I said, that’s one of the things where it’s not at all anecdotal or purely anecdotal or speculative or anything else. It’s just entirely true.

Don’t the French believe in things like vaccine skepticism more than we do?

There is vaccine skepticism in Europe. There’s no question about that. No, that is not uniquely American. The degree to which American have stopped vaccinating their children was higher than anywhere else. We are the mother country of that. It’s not unique to us.

I think of unfounded opinions as falling into two categories. One is religious belief or things like that, which I think are probably pretty deeply held and maybe even partially innate. Then you have a belief like you mentioned earlier, that global warming is fake, which really is not the type of belief that anyone could possibly gain unless they were following very specific news sources that were intent on lying to them. Do you think they are connected?

Yeah, I do, and I think they are synergistic. Climate change is one thing, which of course the Bible doesn’t talk about, but on the other hand, there are things that are both. For instance evolution and creationism, and should evolution be taught without creationism in public schools. That’s where, of course, they overlap.

One thing I’ll say about what I say about religion. Again, I am not a crusading Richard Dawkins–style atheist. I don’t know. Maybe God exists. I don’t know, so I’m not saying, “You people who believe in God, you’re idiots.” I am entirely open to the various shades and flavors and degrees of hunches and religious belief and all that. What I really focus on, and why I focus on it, and why I get down to the specifics of let’s look at what most American Protestant Christians believe, is the extremism of these beliefs. Yeah, do you believe in God? Fine. Do you go to church? Great. Do you believe that Jesus was resurrected? OK, whatever. I don’t know. I don’t, but OK. When we got to faith healing and speaking in tongues and these specifics, which I grant it’s impolite of me to say, “No, this is really nutty,” I’m sorry. It’s important to me to not allow “but it’s my faith” to be the cloak that protects every belief that is a matter of faith from criticism, ridicule, doubt.

So yes, of course they’re different, but to me, they’re not entirely different.

Right, but some of the beliefs America has about religion or conspiracy theories are very similar in other parts of the world, whereas I think it would be very hard for any country in the world that did not have a very specific media environment like America has to not believe in global warming. The first thing feels more universal.

I think that’s true. We can thank the Kochs, among others, for helping create that media environment. Indeed, I talk a lot about the media environment that has been built, the fantasyland infrastructure, that has built in the last 30 years, which has been crucial for sure. But I think in the simplest, most reductionist way, when you start with a people who are so much more prone to rationally insupportable religious beliefs, it seems natural to me that you will also have a country, partly as a result, in which people are willing to say, “Yeah, I don’t believe in climate change, either.” Yes, of course, a media structure arose to teach them that, but a media structure could arise to teach them that in Denmark, and I don’t think you’d end up with half of the Danes believing that climate change doesn’t exist.

Hopefully that won’t happen and we will not be able to test that proposition.

Yeah.

Can you tell me about your personal experiences with our current president, if you’ve had any? And as someone who’s been following him for decades, what do you make of the man you see today and whether there’s anything surprising or different to you about where we are?

I’ve never met him. I have received letters from him threatening legal action, and massive legal action, of course back when I was running Spy magazine. Other than that, my exchanges with him have just been him saying I’m terrible in places like the New York Post. No, I’ve never met him, but I have watched him. I did watch him closely and carefully in the late ’80s, and early ’90s, then stopped for 15 years until six years ago, mostly. People say, “He’s always the same person. He’s a racist.” As much as he was a jerk then—and occasionally, as in the ad he took out saying that the accused and later exonerated Central Park attackers, which indicates evidence of a racialist animosity or racism—the anger and racism and far-right stuff, there was very little evidence of that back in the day. He was a joke. I think what he’s fallen into is because he doesn’t believe much of anything; he has instincts, and I think we’ve seen in the last few days that he has actual instincts about white supremacy, frankly. I don’t think he has well-formed beliefs, but he has instincts, guy-at-the-bar angry instincts. That is his thing. That is his fundamental thing.

What about just watching him as a person? The one thing, as someone who’s watched a lot of old clips of him on Letterman and Howard Stern, is he seems to have less of a sense of irony now. He was always ridiculous, but he had some sense of himself as a character before, whereas now the mask has fallen or slipped, whatever the phrase is.

I think that’s absolutely true. There are many changes. In addition to that fact that he no longer pretends to be in on the joke, and he was always pretending to be in on the joke, but he was more articulate. He seemed happier, frankly. He seemed happier. Look at him. You never see him laugh.

It was very smart of you to publicize him in Spy magazine, therefore ensuring he’ll be president, therefore ensuring you can write a book about America going haywire.

Thank you. It was a very long-term plan, and they seldom work out as well as this one.

Well not for the country, but for you.

Yes, exactly.