In September 1945, the US produced a seminal document called the Strategic Bombing Survey. Air power had been used during the second world war in unprecedented ways and there was a need to reflect on it and learn lessons. The breadth and extent of the survey, which operated from London, was almost beyond comprehension. The forward to the survey states: “Germany was scoured for its war records, which were found sometimes, but rarely, in places where they ought to have been; sometimes in safe-deposit vaults, often in private houses, in barns, in caves; on one occasion, in a hen house and, on two occasions, in coffins.”

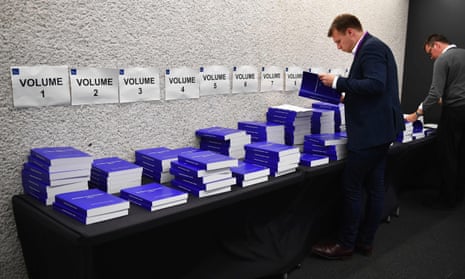

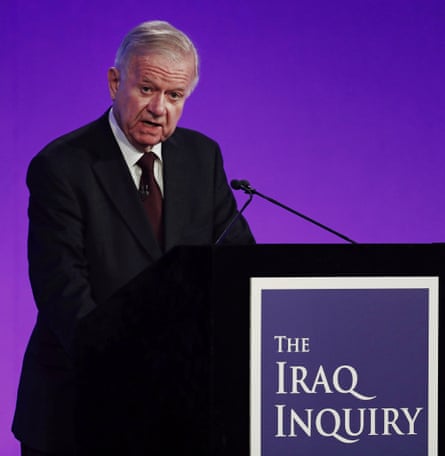

The Chilcot report took seven years to complete and cost an estimated £10.3m. But the Strategic Bombing Survey cost more. “It was necessary, in many cases,” they explained, “to follow closely behind the front; otherwise, vital records might have been irretrievably lost. Survey personnel suffered several casualties, including four killed.”

The survey’s summary used the term “lesson to be learned” only once in a section called Of the Future: “The great lesson to be learned in the battered towns of England and the ruined cities of Germany is that the best way to win a war is to prevent it from occurring.”

The report continued by detailing what those best efforts would entail. “Intelligent long-range planning by the armed forces in close and active cooperation with other government agencies ... a more adequate and integrated system for the collection and evaluation of intelligence information; ... and, finally, in time of peace as well as in war, the highest possible quality and stature of the personnel who are to man the posts within any such organization ... quality, not numbers, is the important criterion.”

We have now had 71 years to absorb these lessons and apply our best efforts towards implementing them in both the US and the UK. What the Chilcot report confirms, to our collective shame, is that we have not. What it does provide, however, is a renewed chance to consider how to apply those same lessons … again. To achieve this, we need to both avoid erroneous arguments while also setting a productive agenda. Unfortunately we are already falling into traps.

One trap involves the impulse to act mechanically, rather than thoughtfully, with the lessons that were detailed (or can be inferred) from the key findings boxes provided throughout the report. This is an error. Since 2006, our own political landscape has changed radically, and so has that of the wider world, meaning that the choices before us are not repeats of the past but matters of consequence that have to be attended to with deliberation and care. The lessons that Chilcot provides, therefore, are not best practices to be blindly applied, but problematics to be addressed.

Another trap is a kind of cynical despair. This involves a toxic mix of concluding that we have learned nothing, and can learn nothing. But this is an unproductive agenda based on false premises. As it happens, governments undertake the policies that they can – not just the ones they want – and that capacity is a function of the tools, systems, policies, mechanisms, and political alliances that are built, sustained, and utilised to direct our conduct. Like the period after the second world war, we now face an era of new technologies, new ideologies, new stresses to the international system, and new imperatives to which we must respond. That means we need to raise our game.

A more productive way to think of the Chilcot report is as a tool to help us set agendas for renewed “best efforts” in creating more effective and accountable statecraft. Chilcot has confirmed that – 71 years later – we still do not have intelligent long-range planning by the armed forces in close and active cooperation with other government agencies; nor an adequate and integrated system for the collection and evaluation of intelligence information; nor do we have the highest possible quality and stature of personnel to lead us through these challenging times.

What we must now do – to rise to the occasion – is embrace a stance of constructive problem-solving rather than become distracted by using the report as a mere foil for political positioning. And key to this is improving the tools that help us make sense of the world, and the others that turn knowledge into a strategic asset in the design of effective and accountable solutions.

Because today, the stakes are too high for bickering, and the world is too complicated to be driven by ideology. We do not want to look back 71 years from now having learned everything all over again, but having done nothing about it.

- The Girl in Green by Derek B. Miller is out now (Faber & Faber, £12.99)