What Happens When You Strap a Camera to a Sea Turtle's Shell

Using a camera strapped to the creature, scientists reveal for the first time the intricacies of how the sea giant hunts.

Submerged in murky seawater, a grey leatherback turtle homes in on its spineless prey, a pink jellyfish drifting through the dark green abyss. The giant turtle glides toward the graceful jelly, opens its mouth, and munches.

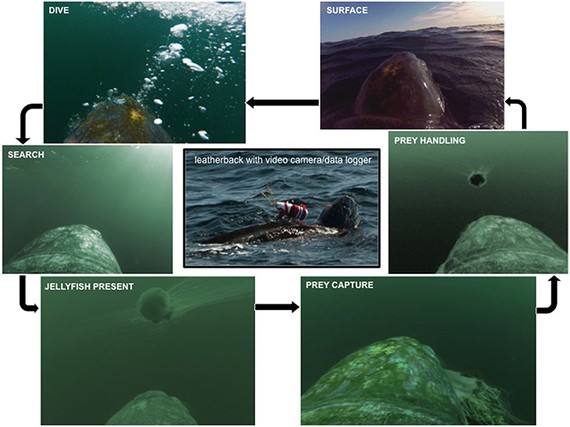

Marine biologists have long known that leatherbacks like to chow down on jellies, but they never knew precisely how. Now, using a camera suction-cupped to the sea creature's shell, scientists have recorded footage of a leatherback's lunchtime for the first time—from the turtle's perspective. Researchers from the non-profit organization the Canadian Sea Turtle Group use the tiny “turtle-cams” to gain insight into the sea turtle’s foraging habits off the coast of Nova Scotia.

“It’s like getting turtle’s home videos—seeing what they see, where they go, and how they acquire vital resources to fuel their natural behavior,” said Bryan Wallace, a researcher with the organization, in a release.

The team found that the turtles perform short, shallow dives when looking for prey. After the turtle catches the jellyfish, the footage shows that it surfaces for a breath before diving down to hunt again. The team reported the details of the turtle's hunting cycle and additional videos on Monday in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution.

But cameras are not the only tech tools helping marine biologists better understand the ocean giants. Embedded satellite tags track where the turtles swim and how deep they dive. So far the group has tagged more than 60 male, female, or juvenile turtles. Although scientists had previously tagged female turtles that climb onto the beach to lay their eggs, the group is the first to tag a male leatherback turtle caught in the ocean.

The marine biologists work with commercial fishermen to find and tag the giant turtles, which can weigh more than 1,000 pounds. Microchips placed in the turtle’s flippers also provide clues to where the animal came from. Scientists aren't sure yet whether all the turtles migrate seasonally, but they do know that they travel very far. Some of the team’s specimens swimming in Canadian waters originated from Colombia, Costa Rica, and Puerto Rico.

Leatherback turtles are an endangered species, so understanding their whereabouts through satellite tags and their hunting techniques with the use of cameras can help researchers better preserve their populations.