The Cost of Corporate Tax Avoidance

America’s largest corporations have been storing profits in offshore companies for decades.

World leaders, celebrities, and even soccer players, a leak from the law firm Mossack Fonseca recently revealed, are fond of using shell companies to avoid paying taxes. While as of yet, few high-profile American names have been linked to the Panama Papers, this sort of tax avoidance is a common practice among a number of well-known U.S. companies, according to a report released Thursday by Oxfam America. The country’s 50 largest corporations have stored more than a trillion dollars in offshore shell companies in recent years to lower their tax rate, the report says.

Large corporations such as Pfizer, Walmart, IBM, and Apple have stashed billions of dollars via more than 1,500 subsidiaries in tax havens like the British Virgin Islands and the Cayman Islands, according to the report, which analyzed the companies’ Securities and Exchange Commission filings. Though this practice isn’t illegal, keeping profits offshore lowers the taxes owed in the United States, and this ends up costing the U.S. government about $111 billion each year in lost revenue, by Oxfam’s calculations.

The 50 largest American companies made about $4 trillion in profit from 2008 to 2014, according to SEC filings, and kept about a quarter of that amount outside the country. Oxfam analysts calculated that these corporations paid an average effective tax rate of 26.5 percent. That’s below the statutory corporate tax rate of 35 percent and lower than what the average American worker pays, which is 31.5 percent.

Of course, keeping profits in offshore tax havens is not the only way a company lowers its effective tax rate. Many of these companies also get tax credits and deductions from the federal government, says Craig Boise, the dean of Cleveland State University’s Cleveland-Marshall College of Law. But still, it’s problematic that companies rely heavily on loopholes in the international tax system to keep some profits from being taxed in the United States. Every time a new rule is created to crack down on abuse, he says, companies find another way around it. “It’s like constantly playing a game of catch-up,” says Boise, whose research focuses on U.S. corporate and international tax policy.

As a result of all this, smaller businesses that don’t have the resources necessary to construct complex tax-avoidance schemes end up paying closer to the full tax rate. This means that they end up paying a larger share of the bill for services such as roads, health care, and education, says Deborah Field, a former corporate tax accountant, whom Oxfam invited to speak on a press call about the report. “I’ve seen how much time and effort companies put into avoiding paying their taxes,” says Field, who now runs a small business in Oregon. “It makes me angry.”

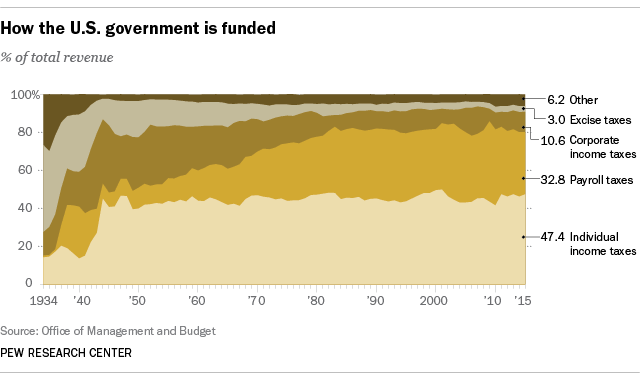

Over the past several decades, corporations have been paying a smaller and smaller share of taxes, according to a Pew Research Center analysis. In 1952, corporate income taxes funded about 32 percent of the federal government. That shrank to 10.6 percent by 2015. While tax havens aren’t the sole cause of this shift, it’s worth noting that the share of corporate profits reported in tax havens has increased tenfold since the 1980s.

The companies that in their SEC filings reported holding the most money offshore include Apple, with $181 billion stored in abroad, as well as Pfizer and PepsiCo, which reported owning the largest number of subsidiaries in tax havens—more than 100 each.

What do the companies have to say about all this? Oxfam contacted the companies for comment, and General Motors, which reported owning 21 subsidiaries in offshore tax havens, responded with this:

“GM does not have, nor use tax havens to reduce or avoid taxes. We do sell cars, parts and auto financing in countries such as Caymans, Ireland, Switzerland, Luxembourg and the Netherlands, and we conduct those sales through GM-owned companies in those countries.”

Phillips 66 reported holding $2 billion offshore from 2008 to 2014, and owned 17 subsidiaries during that time. The company had this to say:

“We operate refining assets in Ireland and marketing locations in Switzerland that provide products to local markets. Singapore is a major trading center for petroleum and we have operations there that support our worldwide Refining and Marketing operations.”

That may well be true, but Oxfam says that offshore subsidiaries generate very little income from local markets, and they are more likely to earn royalties for holding patent rights to products developed elsewhere—which is to say that the fundamental functions of their businesses generally aren’t what’s being conducted in nations with such favorable tax rates.

But tracing all this money requires more transparency. “We would need cooperation from foreign governments to overhaul the system,” Boise says. But many of them don’t have an incentive to do that, because facilitating offshore accounting is such a dependable source of revenue for them.