I'm sitting in the far left corner of Lincoln Center's Alice Tully Hall in New York, in a dark spot under the balcony, watching a man who is not a man.

On the brightly lit stage, the man sits comfortably in an Aeron desk chair, hair falling into his eyes as he gazes idly about the room through glasses, hands in lap. The emcee of the Global Future 2045 conference, Phil VanNedervelde, introduces him as Dr. Hiroshi Ishiguro, director of the Intelligence Robotics Laboratory in Osaka, Japan. He's a leading expert in the creation of lifelike robots. As VanNedervelde steps off stage, the man looks around at the crowd and begins to speak.

"In order to investigate humans, we need to have a test bed. I am the test bed," he says. "The professor is using myself to study the Hiroshi likeness. I am the most important research he has out... Now, let's welcome professor Ishiguro." With that, the professor himself strides onto the stage and the "man" in the chair is revealed as Ishiguro's hyperrealistic robotic doppelgänger.

Wait 30 years, and the distinction between the "man" and the "machine" might not be so easy to make. If the conference organizer, Russian multimillionaire Dmitry Itskov, has his way, robots like Ishiguro's will make us immortal—perhaps as soon as 2045.

Consciousness transfer

The conference I attended in June is the product of Itskov's 2045 Initiative, which has set itself the goal of transferring "an individual's personality to a more advanced non-biological carrier." The side effect of that ability to transfer personalities would be that one never has to die with a body; they would become, potentially, immortal.

Itskov made the money that funds the 2045 Initiative with a blog about the Russian Internet, tarakan.ru, and an online newspaper, Dni.ru, according to a New York Times profile. This developed into a company, New Media Stars, with ties into the Russian government. Partial ownership of the company eventually made Itskov rich, but it did not prove fulfilling. Itskov, who now lives more like an ascetic monk than a tech multimillionaire, spends his life promoting the 2045 Initiative in the hopes of overcoming humanity's limited span of years.

The first step in Itskov's plan is creating android avatars that are controllable by a brain-machine interface. According to the 2045 Initiative, this will give humans the "ability to work in dangerous environments" without personal risk. The androids, which are somehow both more capable and more expendable than the average human, should appear by 2020 if all goes well.

By 2025, the medical and technological communities should work out how to make an "autonomous life support system for human brains," to save people whose bodies are "worn out." Once the brains are pickled away in their Mason jars, the goal is to recreate the brain as a kind of computer by 2030, enabling people to transfer their consciousnesses to another host. These minds that are now "substrate-independent" should eventually be transferable into new bodies with "capacities far exceeding those of ordinary humans." In sum: transferable consciousnesses into artificial bodies by 2045.

The 2045 Initiative's mission, described more broadly, is associated with the "technological singularity," the point at which humans achieve superintelligence aided by technology. The singularity is the Big Bang but reversed. With the Big Bang, the shift of everything into existence was so sudden and radical that we don't currently have a reasonable way of figuring out what came before. Proponents of the singularity say that the changes would be such a significant tipping point in the way our world operates that we have no way of predicting what will come after.

We can look to the greats of science fiction for some predictions on what might come of a singularity. They almost universally foresee disaster—the Cylons of Battlestar Galactica, the replicants of Blade Runner, the circumventions of Asimov's laws of robotics. Supporters of the singularity see more upsides.

While Itskov has a general plan, the specifics of getting to consciousness transfer by 2045 remain murky. Even the question of how to achieve the first landmark goal in GF2045's timeline—affordable android avatars controllable by brain-machine interfaces by 2020—is yet unanswered. Skeptical, I attended the conference hoping to see someone, anyone, indicate that even the first step of the 2045 Initiative's timeline was attainable, let alone practical.

The personal motivations of the singularity have to do with overcoming the “imperfections” of humans: we are temporary, physically restricted in capability and location, and not smart enough. Each of us dimly ambles through life and makes the planet a little worse with each pass. Singularity boosters aren’t the first sect to target immortality, but they might be the first group motivated enough to try to systematize it.

The morning of the first day of the conference, the lobby was quiet as a few dozen attendants milled around while a flute and guitar filled the room with high-brow music. I started talking to a wide-eyed gentleman who sang the praises of TA-65, an expensive “telomerase activator” that is supposed to slow the aging process. “When I’m about 35, I’m probably going to start it,” he said.

The young man said he was at the conference to see longtime singularity booster Ray Kurzweil. He had not read any of Kurzweil’s books, but he watched his videos online. “You’ve heard of YouTube?” he asked.

Some supporters of the singularity movement tend to be focused on their personal well-being. At a minimum, they want to live as long as possible so they can live to see the advancements that will make them smarter and better.

But the singularity also has a larger purpose to them. Refining humans to perfect living, feeling androids would bring immortality, the reduction of disease and suffering (as we know them from our human position anyway), and the ability to regulate people's needs in a way that is compatible with a planet and ecosystem that prove time and again to be too fragile to compete with our wanton desires for power, convenience, and dominance.

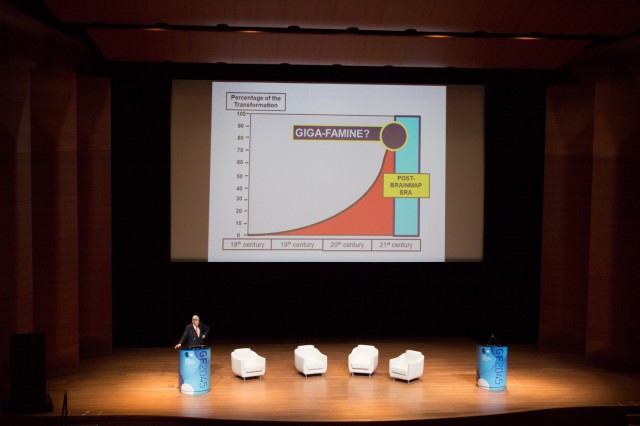

Dr. James Martin, an IT consultant and early employee of IBM, opened the conference with an hour-long rundown of the problems facing the planet (like climate change) and how they are influenced in large part by an overgrown human population. Dr. Martin called this "the make or break century," the moment we could see "the birth of a global renaissance or things descend into chaos. Or both." Put more succinctly, things will change.

As Martin ran through his list of damning statistics—including the frightening number of cows and their resulting volume of gas emissions—it's hard to shake the feeling that the presentation is a massive troll of a room full of people who have at least a passing interest in living forever. We're ruining the planet because... we're living too long and reproducing too often? Obviously the solution is to advance technology to the point where no one needs to die!

But Martin pointed out that a state of consciousness housed in some abstraction of a human body might lead to huge advantages. An android doesn't need all those cows, for instance—or even a temperate planet. As I listened, it hit me: Dr. Martin was describing all of the problems that won't be problems once people aren't people anymore.

Martin's consciousness won't be one of those transferred to an android, however. Several days after speaking at the conference, Martin passed away in a swimming accident.

reader comments

172