As Islamic State forces swept into ancient Palmyra Wednesday evening, they would have paid scant attention to the long Roman colonnade that stretched out before them.

Looking for cover in the event that the fleeing Syrian forces might mount a counterattack, they likely would have paid closer attention to the extensive remnants of the magnificent Roman theatre, or the ground around some of the massive arches that still stand along the road and offer protection.

They must also have wondered if any Syrian stragglers were hiding in the medieval citadel that overlooks the site, giving them a fine position from which to fire any weapons.

But IS leaders would have known the greater significance of what they had just captured: one of the finest archeological sites in the Middle East; a place that tells some of the history in this so-called “cradle of civilization” that archeologists call Mesopotamia.

“Palmyra is one of the best-preserved sites of classical antiquity in the entire world,” said Eric Meyers, professor emeritus at Duke University. Its evidence of the blending of Semitic, Roman and Persian cultures makes it “one of the most important UNESCO World Heritage sites,” he said.

The city, known by its Semitic name, Tadmor, is mentioned in the Bible as a place fortified by King Solomon.

And, as IS commanders know, its destruction will send shock waves around the world and draw attention to their movement as nothing else can.

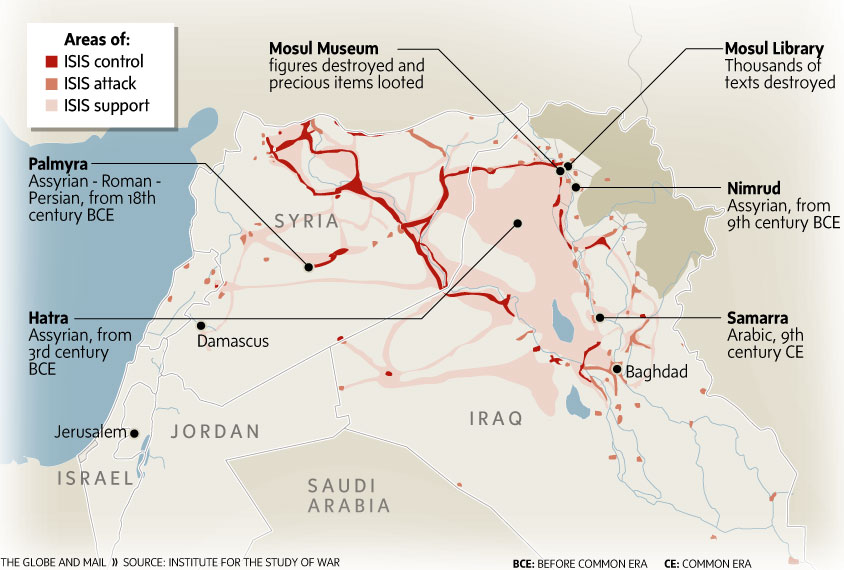

Islamic State already has laid waste to important archeological sites in Iraq, including Nimrud, which once was the capital of a vast Assyrian empire that stretched from what is now Iran to southern Egypt. Videos of IS fighters smashing 2,400-year-old statues and burning thousands of books and manuscripts in the Mosul museum have gone viral.

This destruction is not just about laying waste to anything that predates the 7th century arrival of the Prophet Mohammed and the Muslim faith he fostered. It’s more a political than a religious statement; one that assists greatly in recruiting jihadis around the world.

“The destruction is their way of getting back at us [in the West],” said Clemens Reichel, curator of Mesopotamia at the Royal Ontario Museum who has worked extensively in the region. “They know how much we value these historic places.”

Anyone with an axe to grind against Western powers knows where they can sign up.

The loss to historians is incalculable, archeologists say, though Dr. Reichel is quick to point out that even if the visible remnants of Palmyra are destroyed “our work will go on.”

What can be seen of the ancient city is just a tip of the iceberg, he says. “What remains to be excavated is much vaster.”

“The more important loss is to the Syrian people,” said Dr. Reichel. “This place is a big part of their national identity. It has linked Muslims, Christian, Druze … everyone. Its history is one thing they all have in common.”

“That seems to be exactly what Islamic State wants to destroy,” he said: “their sense of historic identity.” They want the people only to identify with the Prophet, he concludes.

Throughout the millennia, Palmyra has been severely damaged by successive military campaigns from Romans, Persians, Arabs, Mongols and Turks. “But each conqueror built something special in its place,” Dr. Reichel said. “Islamic State seems only to want to take – to take away diversity, to destroy places of pilgrimage and historic monuments. I don’t see it adding anything.”

World heritage is under threat

NIMRUD

Founded in the 13th century BCE, Nimrud, 30 kilometres south of Mosul, was capital of the vast Neo-Assyrian empire in the 9th and 8th centuries BCE. Most of its priceless artifacts were removed years ago to museums in Mosul, Baghdad, Paris, London and beyond. However, impressive reliefs and statues of giant lamassus – winged bulls with human heads – remained on the site. Videos from early March show IS members using sledgehammers to destroy a lamassu statue, and bulldozers knocking down walls. Explosions purported to show the complete destruction of parts of the site.

HATRA

A UNESCO World Heritage Site, Hatra, 300 km northwest of Baghdad, flourished from the 3rd century BCE to the 3rd century CE, and was considered the best-preserved example of a city built during the Parthian Empire. It was fortified and withstood attacks for centuries. Its temples and statuary showed the people paid homage to various deities. Despite being safeguarded by 1,400 years of various Islamic regimes, the city was targeted earlier this year by Islamic State, determined to erase from the Earth anything resembling idolatry.

MOSUL MUSEUM/LIBRARY

Some of the region’s most important artifacts and manuscripts were moved to the museum and library in Mosul to allow for better display and greater protection. In February this year, however, IS followers were videotaped smashing many of the statues and reliefs on display. Thousands of books, including manuscripts from early Ottoman periods were shown burning. “The video was sickening,” said Clemens Reichel, Mesopotamia curator at the Royal Ontario Museum. “It reminded me of the book-burning in Germany in the 1930s.”

PALMYRA

Sitting at the main crossroads in central Syria, Palmyra, 200 km northeast of Damascus is a blend of several cultures and is considered one of the greatest archeological sites in the Middle East. Founded in the 18th century BCE, the Semitic city was fortified by Israel’s King Solomon, and enjoyed great prosperity during the Hellenistic and Roman periods, while maintaining autonomy. Many of its most important structures have been excavated and remain standing, though the entirety of the unexcavated ancient sections are thought to be several times as large.

NEXT ON THE LIST: SAMARRA

The nearest site on Islamic State’s to-be-destroyed list are found in Samarra, in central Iraq, just out of reach of IS forces who recently captured nearby Ramadi. Though built after the dawn of Islam, the 9th century al-Askari Shrine of two of Shiism’s original imams is considered heretical by the extremist Sunni IS leadership, though sacred to Shiites. Which is why Iraqi and Iranian military leaders rushed Shia militiamen to the city a year ago as soon as IS forces headed in Samarra’s direction.