Earlier this week, a neo-Nazi teenager who built a homemade pipebomb was sentenced to a three-year youth rehabilitation order. The 17-year-old, from Bradford, had posted a message to Facebook on the day MP Jo Cox was murdered, praising her killer. “Tommy Mair is a HERO,” he wrote. “There’s one less race traitor in Britain thanks to this man.”

Court hearings revealed that the teenager had been recruited online by the secretive neo-Nazi group National Action, which was banned by the government in December 2016, becoming the first rightwing group in the UK to be proscribed under terrorism laws. In a chatgroup found on the boy’s phone, members discussed blowing up mosques and mimicking the methods of the IRA. The charity Hope not Hate warns that National Action has been “emboldened” by the ban and continues to be active, while the government anti-radicalisation group Prevent reports that one in 10 cases referred to it involve far-right extremism, rising to one in four in some parts of the country.

Nationalist propaganda has moved into the mainstream. Breitbart News, the far-right outlet once led by Donald Trump’s chief strategist Steve Bannon, is launching new sites in Germany and France. Breitbart London has already launched, and a cursory glance at its front page shows stories pushing three simple messages: migrants are bad; Muslims are bad; the EU is bad.

In light of the spread of far-right bigotry and misinformation, Theresa May’s government has launched a campaign to fight back. As part of a £60m government project, the advertising group M&C Saatchi will be tasked with combating the increasingly widespread influence and propaganda of the so-called “alt-right”. The Home Office put out a statement on the day the new campaign was reported: “This government is determined to challenge extremism in all its forms including the evil of far-right extremism and the terrible damage it can cause to individuals, families and communities.”

Taking on the alt-right is not the usual sort of ad agency brief, but M&C Saatchi has run many successful political campaigns. Its mantra when it comes to political communications has always been: “Hit first, hit hard and keep on hitting.” Its work has courted controversy for its ruthless and often negative tone. In 1997, it caused controversy with its “New Labour, New Danger” poster, depicting Tony Blair with a menacing set of demon eyes, an image so shocking that even the church complained about its satanic undertones. But its methods usually work.

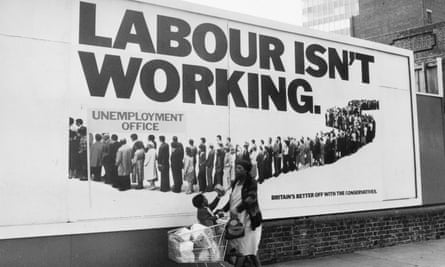

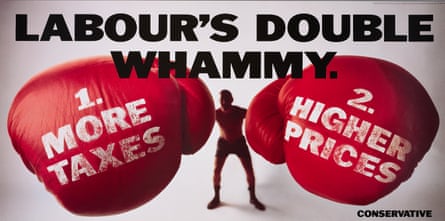

The Saatchi team are past masters at taking complex political ideas and boiling them down to bold, concise messages. Maurice Saatchi calls it a “brutal simplicity of thought”. It has served the agency, and the Tories, extremely well. Posters such as 1978’s “Labour Isn’t Working”, 1992’s “Double Whammy” and 2015’s image of a subservient Ed Miliband tucked into Alex Salmond’s breast pocket shaped debate and defined campaigns.

But the landscape the agency is now operating in is very different from the cleanly polarised battlefield of electoral politics. M&C Saatchi is not being asked to attack the Labour party or promote the merits of the Tories; it is being asked to combat an enemy that is altogether more abstract, in a contest where there is no clear finishing line. In the complex, confusing and ceaseless battle of ideas that takes place every second of every day across the internet, what role can a traditional ad agency possibly play?

The agency is reticent about discussing the details of its government brief. It says its role is not to deliver a national ad campaign, but rather to support the work of civic groups around the country that are already working in communities to steer people away from extremist ideas. It is assisting in various ways, from straightforward logistics, such as helping small organisations to build websites, to strategic advice on how to identify and engage with particular audiences. Its job is not to define the message, but to offer creative advice to others where needed. It might be as simple as helping with how to word a headline on a leaflet or a post on Facebook.

“It will be under-the-radar stuff,” says Benedict Pringle, editor of the website PoliticalAdvertising.co.uk, who has studied in detail M&C Saatchi’s past political work. “If we see their work, then they will probably be doing something wrong.” In other words, the agency will be an invisible hand, guiding the communications of various other groups involved in the fight against extremism.

“What they will be good at is to help get into the mindset of the audience, and identify the strings they can pull to make them think again,” says Pringle. “They will be able to advise on media strategy: finding the best channels through which to communicate with the right sort of people. So they might monitor conversations on social media platforms and intervene in them in ways that might help change behaviour.”

This is something the agency gained experience of during the 2015 general election campaign, much of which was fought by micro-targeting small groups of floating voters online using bespoke messages. “We had a single message that proved successful in 2015 about a long-term economic plan,” says Tom Edmonds, who ran the Conservatives’ digital operation in 2015 before founding the consultancy Edmonds Elder. “It was about knowing how that same message relates in different ways to a housewife in Devon or a mechanic in Derby.”

Edmonds says that the ad agency will be trying to find the equivalent of the fabled “floating voter” in the fight against extremism. “There is no point trying to convert the hardcore extremist,” he says. “I think they will try to run a very tightly targeted campaign aimed at people who have expressed casual interest in certain far-right ideas or shown some sort of intent to get involved. They will then have to find ways of running messages that resonate with them and relate to their lives and values.”

Danny Brooke-Taylor, founder of the ad agency Lucky Generals, who worked on Labour’s 2015 campaign, says strategic targeting is one of the main skills the ad industry can bring to politics. “There’s a risk that this kind of campaign is simply circulated among liberals and fails to reach, let alone engage, people with extreme views,” he says. “Obviously, some of these will be immune to any communication – but there are always less committed types, who hold the views less strongly, and simply circulate what they genuinely believe is true, without interrogating it too much.”

He says that once the audience is identified, the creative techniques of traditional advertising could still have a role to play. “The obvious strategy is to correct false news using the true facts. And no doubt that should be part of the approach,” he says. “But simply trading statistics in tit-for-tat style doesn’t actually get you very far. There’s loads of evidence that human beings make most of their decisions based on emotions. So, contrary to what politicians often say, the facts won’t speak for themselves. They will need to be wrapped up in powerful images, memorable turns of phrase, striking metaphors, shareable infographics, and so on.”

Approaching the subject-matter with humour might be the best way to defuse the anger and vitriol of the right, says Brooke-Taylor. “Sometimes, the best way to demolish myths is to make fun of them,” he says. “Ridicule can be a really powerful weapon to put bullies back in their place or to point out the flaws in an argument. An additional benefit of humour is that it’s more likely to be shared. This shouldn’t be mistaken for advocating a flippant approach – sometimes a smile can be used to make a devastatingly serious and effective point. Or, as Robin Williams once said: ‘Satire isn’t dead – it’s alive and living in the White House.’”

Brooke-Taylor agrees that M&C Saatchi would be wise to keep its involvement – and that of the government – as low-key as possible. “Ultimately, this campaign’s from the government,” he says. “But part of the far right’s rise is precisely because of a distrust of the authorities. So the branding will be important, if the message isn’t to be rejected because of the messenger. Maybe influencers will have a role to play here? People who don’t conform to the usual ‘snowflake’ stereotype (whether we like it or not) and have more credibility with this audience?”

The Saatchi team have always had a sharp eye for the close relationship between advertising and public relations. In 1992, they handed out easy-to-use “tax calculators” to the press, allowing individuals to quickly determine how much more tax they would pay under a Labour government depending on their profession. It was a rudimentary sliding scale made from cardboard that hammered home their key campaign message in a way that voters could understand and relate to. It got a lot of press coverage, and the public strove to get their hands on the calculators. It was as close to viral content as it got in the early 90s.

“That sort of creativity is about treating the audience with respect and intelligence,” says Dave Trott, creative director and author of the books Creative Mischief and Predatory Thinking. “That means not simply trying to shout down the opposition by contradicting what they say and calling them stupid. People were very quick to brand everyone who voted leave as racist during the Brexit debate, which only drove people further the other way.”

All the best creative thinking, says Trott, goes back to the work of Bill Bernbach, the legendary US adman who created iconic 60s campaigns for Volkswagen and Avis. He was brutally honest about both the failures and the merits of the brands. He celebrated that Avis was second in the car hire market to Hertz by conjuring the slogan: “We try harder.” His poster for the Volkswagen Beetle urged consumers to “Think small”. “He wasn’t trying to tell people that the Beetle was the sexiest car around,” says Trott. “He was appealing to their rational minds by telling them it was the practical and reliable choice. Audiences respond well when you give them the right information with which to make their own smart decisions. They do not like being lectured. And that is particularly true in politics.”

But it might be that the government is fighting the wrong enemy. “The far right is actually in decline in this country,” says Matthew Collins, author of Hate: My Life in the British Far Right. “Their numbers are dwindling. The real problem is the way that some of their ideas have already been absorbed by the mainstream. Some of the stuff that the BNP was saying in 2010 about immigration and so on is now considered quite acceptable in the mainstream media.” What’s more, Collins suggests, the government might be looking to do battle in the wrong place. “Attacking the fringes is no longer the issue. Why aren’t the government looking at the fact that some voices in the mainstream think it is acceptable to say deeply offensive stuff with no concern for the feelings of others?”

In any case, Collins is unconvinced that advertising is capable of changing anyone’s minds on extremism. “No ad can convince people that their lives are better than they actually are,” he argues. “Do M&C Saatchi understand exactly why some of these ideas are actually attractive to a lot of people? Probably not. My concern is that they are trying to counter an idea that can’t be countered by spin alone. It takes hard work. The only way to stop people being vulnerable to far-right ideas is to meaningfully change the circumstances of their lives.”

The team at M&C Saatchi say their job is to help community groups; that they will help those groups identify and engage with those most vulnerable to extremist ideas. Posters and cardboard handouts might no longer be the means of communication, but the same principles still apply.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion