Star Wars: The Force Awakens may be one of the highest-grossing films ever released, but it is also one of the most depressing. However delighted our heroes are to destroy the Death Star – sorry, Starkiller Base – the overriding message is that such triumphs are meaningless; specifically, the triumph that rounded off the previous Star Wars episode, The Return of the Jedi. When we saw it in 1983, we couldn’t have envisaged a sweeter or more total victory. There were parties on every planet in the galaxy, Leia was cosying up with Han next to a bonfire, and Darth Vader had redeemed himself by chucking someone down one of those 100-storey maintenance ducts that the Empire’s health-and-safety-defying architects are so fond of. Everything was awesome.

But The Force Awakens renders all that null and void. The galaxy it presents is one where the planet-smashing conflict is still rolling along and where the bad guys are as powerful as ever. In other words, Luke Skywalker and his pals achieved precisely nothing. Thanks to JJ Abrams, the happy ending of The Return of the Jedi is now neither happy nor an ending.

And don’t expect the current trilogy to offer any closure. Last week, Bob Iger, the CEO of the Walt Disney Company, confirmed that Star Wars: Episode IX, due in May 2019, won’t be the last of the Star Wars films. “There will be more after that,” he said. “I don’t know how many, I don’t know how often.” So even if Episode IX concludes with Finn marrying Poe Dameron, the big holographic villain being switched off, and you-know-who turning out not to be dead, after all, there will be no reason to celebrate. Any ceasefire in the Star Wars universe will be as temporary as a Christmas Day truce.

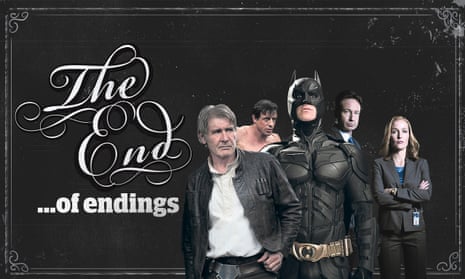

It’s not just Han and Leia who aren’t being allowed to live happily ever after, either. More and more film franchises are spoiling their heroes’ retirements, thus snatching away the simple pleasure we once got from picturing their pipe-and-slippers contentment. Take Creed, for example. Sylvester Stallone had wrapped up the story of his punch-drunk alter ego numerous times over the decades, but 2006’s Rocky Balboa seemed to be the real deal. Rocky was finally at peace. Or so we assumed. But Ryan Coogler’s torch-passing drama yanks the champ away from his cosy neighbourhood restaurant, inflicts cancer on him, and forces him to watch as his protegé embarks on a series of fights as bloodily punishing as his own. Both Rocky and Han Solo must have been tempted to quote Michael Corleone in The Godfather: Part III: “Just when I thought I was out, they pull me back in.”

Have we reached the end of endings? In The Dark Knight Rises, Bruce Wayne turned his back on both Batman and Gotham City so he could swan around Florence with Selina Kyle. But in this year’s Batman v Superman, the poor chap is having to squeeze into his rubber suit once again. Similarly, Iron Man 3 was the third part of a trilogy, and it was just as valedictory as The Dark Knight Rises. It finished with Tony Stark blowing up his robotic armour and lobbing his high-tech pacemaker off a cliff, so that he could settle down with his girl Friday, Pepper Potts. But it wasn’t to be. In Avengers: Age of Ultron, he had his full metal jacket back on, and there is no chance that he’ll take it off again soon. Like the characters in Star Wars, Iron Man and his buddies are owned by Disney, which means that Iger gets to decide their destiny. “[With] Marvel, you’re dealing with thousands and thousands of characters,” he said last week. “That will go on for ever.”

There are some superhero fans, I know, who will be overjoyed by this promise, but I’d argue that the true fan would prefer his or her idols to have some well-earned downtime.For instance, the last X-Files film had Mulder and Scully living together in a secluded cottage, which is just what the pair’s devotees had always prayed for. But now a new television series of The X-Files has begun, and in it we learn that – surprise surprise – Mulder and Scully have long since split. And so another happy ending goes up flames. In Independence Day in 1996, Will Smith’s Steven Hiller saved the earth from aliens. Surely, after that, he deserved an easy life of book tours and medal ceremonies. But it’s now been announced that Hiller won’t be in this summer’s Independence Day: Resurgence. Apparently, he was killed while testing a jet fighter developed using those aliens’ technology – so it looks like the bug-eyed monsters had the last laugh.

Sequels are nothing new, of course. And it’s not unlike Hollywood to milk their cash cows until they moo for mercy. What has changed is that viewers are no longer being given – to quote Frank Kermode or Julian Barnes – the sense of an ending. What we used to get from our blockbuster movies was the comforting illusion that even the most mountainous obstacles in life could be surmounted in a couple of hours – and that those obstacles would stay surmounted. Certain characters would go on to face other challenges in sequels, it’s true. But we always knew that after two or three films, our heroes would move beyond the most stressful periods of their lives. Marty McFly could marry Jennifer, the Ghostbusters could hang up their proton packs, Indiana Jones could literally ride off into the sunset. And to many of us, that fairytale fantasy was one of cinema’s most attractive aspects. It wasn’t like watching football, in which one Saturday’s win could be followed by another Saturday’s loss, or a soap opera, in which a family’s troubles would grind on ad infinitum. The movies had what media analysts are now calling “finishability”. James Bond aside, their characters had one or two major crises in their lives, whereupon they could look forward to indefinite rest and recuperation.

Not any more. Today, popular culture has been geekified to the point where fans can take to the internet in their thousands to demand more content about their favourite characters, and where corporations are only too glad to monetise those demands. Say what you like about George Lucas’s mismanagement of the Star Wars films, but at least he wouldn’t make a new one unless he really wanted to. Under his stewardship, the gang’s further adventures remained the stuff of fan fiction and spin-off novels. That was what made the films themselves so special. (Well, the original trilogy, anyway.) Now that the franchise is owned by Disney, it is no longer an option for the saga to come to a satisfying conclusion. The company’s shareholders would revolt if Iger didn’t declare Star Wars to be a never-ending story.

This no-end-in-sight tendency is cropping up in other art forms, too. In prose, PD James used Death Comes to Pemberley to curtail Lizzie and Darcy’s domestic bliss. On television, we have had the fan-prompted revivals of Arrested Development, Futurama and the aforementioned X-Files. And on stage, there is the nerve-racking prospect of JK Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Cursed Child. After everything Harry has been through, says Rowling’s website, he is now “an overworked employee of the Ministry of Magic [who] grapples with a past that refuses to stay where it belongs”. But his best mate may be faring even worse. “I would expect Ron has probably divorced Hermione already,” said Ron Weasley himself, Rupert Grint, in an interview last week. “He’s living on his own, in a little one-bedroom apartment. He hasn’t got a job.” Thanks for that, Rupert. Thanks a lot. It’s not exactly “all’s well that ends well”, is it?

Still, as dispiriting as the continuations of The X-Files and Harry Potter may be, it has always been in the nature of novels and television programmes to stretch into long serials, whereas, ever since the decline of the silent-era cliff-hanger, cinema has specialised in discrete stories that left the characters’ after-lives to the viewer’s imagination. If blockbusters are now going to replace every “The End” with a “To Be Continued”, they will lose this essential part of their appeal. Why see a Star Wars episode when you could just skip it and see the next one, or the next one, or the next one after that?

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion