A surge in self-employment and temporary or part-time jobs over the past two decades has been a key factor behind the rise in inequality in the world’s industrialised countries, according to a major new study by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

The Paris-based club, which has been a driving force in arguing that increasing inequality jeopardises economic growth, says more than half of all job creation in its 34 member countries since the mid-1990s has been in “non-standard work”, which accounts for about a third of total employment.

With such jobs tending to be lower-paid and less secure than their full-time, permanent equivalents, some economists have described this phenomenon as the rise of a “precariat” – and the OECD says the growing prevalence of non-standard work has widened wage inequality.

“Non-standard workers are worse off in terms of many aspects of job quality. They tend to receive less training and, in addition, those on temporary contracts have more job strain and have less job security than workers in standard jobs. Earnings levels are also lower in terms of annual and hourly wages,” the OECD says.

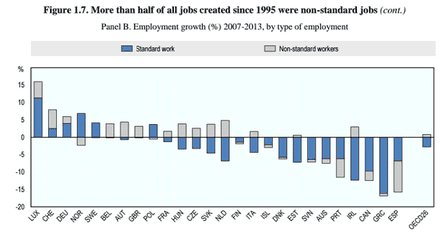

“In the six years since the global economic crisis, standard jobs were destroyed while part-time employment continued to increase,” it says, in the new report, In It Together: Why Less Inequality Benefits All, the latest in a series on inequality.

In general, inequality has tended to rise across OECD countries in recent decades. The report says that the richest 10% of the population now earn 9.6 times the income of the poorest 10%, up from 7 times in the 1980s – and the shift to non-standard work has played a role.

Temporary staff in particular tend to suffer a “wage penalty” relative to their permanent colleagues, the OECD finds. “Compared with permanent workers, temporary workers face substantial wage penalties, earnings instability and slower wage growth.”

TUC general secretary Frances O’Grady said: “We cannot build a secure recovery off the back of zero-hours contracts and weaker employment rights. If we don’t create more decent jobs inequality will continue to soar and the economy risks running out of steam.

“The hire and fire culture of recent years has allowed unscrupulous employers to hold down pay and make staff survive off scraps of work.”

In the UK, where the growing use of zero-hours contracts was an issue during the UK’s recent general election campaign, the OECD finds that non-standard work has accounted for all the net jobs growth since 1995.

The OECD also debunks the idea that non-standard work is always a short-term stopgap, while employees wait for a permanent role to come along. “Non-standard work is not always a stepping stone to stable employment. Temporary contracts increase the chances of acquiring a standard job compared with remaining unemployed, but a part-time job or self-employment does not increase the chances of a transition to a standard job.

The process of replacing permanent, full-time staff with non-standard work has contributed to the polarisation of today’s workforce, between highly-skilled, well-paid jobs and lower-paid, low-skilled ones, the OECD finds – a process some experts have blamed on technological change.

“Since nearly all job losses, regardless of the type of task, were associated with regular work, while growth in employment took place mainly in the form of non-standard employment, technological advancement alone cannot be the only explanation for job polarisation. Labour market institutions and policies have also probably played a role,” it says.

The OECD calls for government action to improve the prospects of lower-skilled workers in the labour market: “The focus must be on policies for quantity and quality of jobs; jobs that offer career and investment possibilities; jobs that are stepping stones rather than dead ends.”

It also calls for governments to adopt a series of other policies to tackle inequality and mitigate its impact, including encouraging women to enter the workforce, using the tax system to redistribute income towards the poorest families, and improving education.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion