Why Are the Republican Debates Limited to 10 Candidates?

Fox and CNN have chosen a cutoff that neither accommodates all of the candidates nor facilitates a satisfying debate.

In an increasingly quantified and poll-obsessed political world, it’s not often that you get arbitrary numbers. A rare exception came Wednesday, when CNN and Fox both released their guidelines for 2016 Republican debates—coming to a swing state near you, this fall! The most discussed, and curious, element in the rules set was the number of candidates who will be allowed on stage: an even 10.

Fox’s standard for an August debate in Cleveland is fairly straightforward. A candidate “must place in the top 10 of an average of the five most recent national polls, as recognized by FOX News leading up to August 4th at 5 PM/ET. Such polling must be conducted by major, nationally recognized organizations that use standard methodological techniques.”

CNN uses a similar but more elaborate standard for its September 16 debate at the Ronald Reagan Library:

The first 10 candidates—ranked from highest to lowest in polling order from an average of all qualifying polls released between July 16 and September 10 who satisfy the criteria requirements ... will be invited to participate in 'Segment B' of the September 16, 2015 Republican Presidential Primary Debate.

But then it takes a weird turn. CNN also creates a loser’s bracket (or as the Atlanta Journal-Constitution calls it, a “kid’s table”) for candidates who are polling at 1 percent or higher in three national polls but don’t otherwise meet the requirements. They’ll appear in a separate segment of the same debate, a rather limp consolation prize.

There have been controversies over who gets invited to a debate before—you could ask Dennis Kucinich or Gary Johnson, though they’d probably be happy to tell you even if you don’t ask. But usually the question is cutting out the candidates who don’t seem to be a real factor, not about making sure you can fit them all on stage.

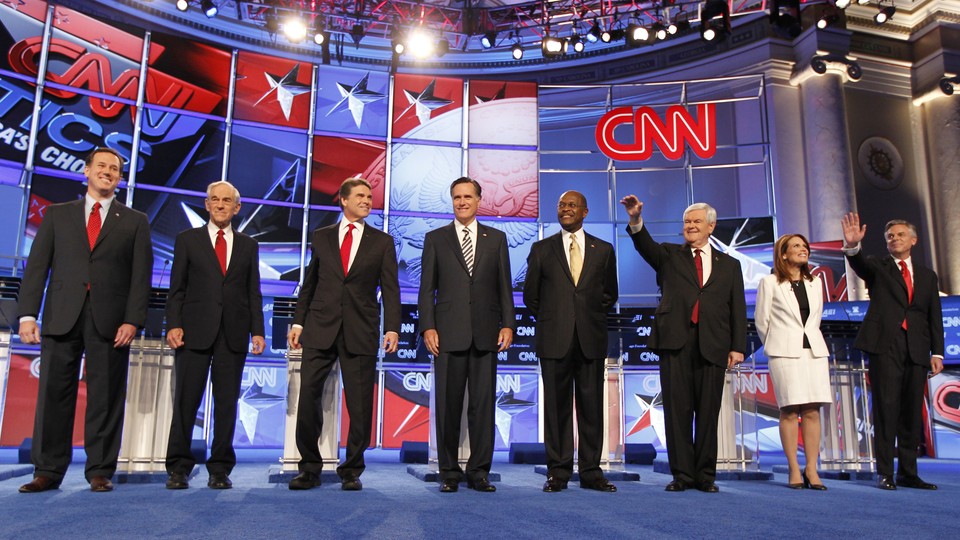

This year, the problem is that the Republican Party simply has too many legitimate candidates. It’s not that there haven’t been large debates before—the Republicans had as many as nine candidates for a debate during the 2012 cycle, and Democrats topped out at eight during the 2008 cycle. But in each of those cases, they were including every plausible candidate, plus often at least a couple who weren’t plausible. (Sorry, Mike Gravel.)

But the 2016 field seems unique. It’s fairly easy to name some members of its top tier, which includes Jeb Bush, Scott Walker, and Marco Rubio. But it’s hard to design a criterion that makes a great deal of sense for sorting the rest. What’s strange is not that there are so many candidates, since there are often plenty of long shots. What’s strange is that there are so many candidates who could plausibly go a long way in the field, but who also might burn out early.

How high is Rand Paul’s ceiling? Is Ben Carson a serious candidate? Is he more serious than, say, John Kasich, an experienced politician who’s polling well behind Carson? (One strange artifact of the rules is that if the cutoff were today, the debate in Cleveland would exclude Kasich, who is governor of Ohio.) Should Carly Fiorina be on stage? Especially at this early point, it’s hard to know who will sink into oblivion (or remain mired there) and who will rise. Anyone seeking proof of this volatility need only look at the dizzying changes on the GOP leaderboard in 2012.

And yet it’s very clear that the field needs to be limited. The 2008 and 2012 examples showed that eight and nine candidates are simply too many. The result is something more like a round-robin quiz than a debate—every candidate can answer a question, but it’s hard to create any serious discussion or exchange of ideas, and the only way a candidate can delve into a topic is at the expense of his or her rival’s given time. In fact, 10 is likely to be far too many for any conversation, too, meaning that the networks have chosen an arbitrary limit that neither accommodates all of the candidates nor facilitates a satisfying debate.

The GOP has an especially diverse field of candidates this year, including Carson, Fiorina, and Bobby Jindal. But as Joshua Green noted, there’s a danger that the rules could end up knocking out some of that diversity. Neither Fiorina and Jindal would make the cut if the cutoff were today, using RealClearPolitics’ rankings.

But 10 is a nice round number, and it’s also the number of buttons on a standard telephone keypad—which may not be a coincidence. Steven Shepard noted last week the challenge facing pollsters right now. “There are 19 Republicans seriously considering launching campaigns for president, and 10 numbers on a phone. That causes a big problem for pollsters using automated polling technology, one of the most common forms of public polling,” he wrote. Some pollsters like to include an undecided option—knocking the number of available slots down to nine. The result is that it’s very hard to design and execute a reliable automated survey that accounts for the entire field. (Non-automated polls, meanwhile, are extremely expensive and time-consuming.)

One last complicating factor: With a field this large, at this early stage, and with a month between debates, the top 10 candidates in the field could be a substantially different group at the two debates. That will make for some freshness, but it’s not the best way to guarantee continuity of discussion, especially with a small battalion of hopefuls behind podiums. Perhaps the debates will at least produce some funny memes, outlandish wagers, and … uh, I forgot the third thing. Oops.