Sergei Eisenstein was the most notorious filmmaker in the world in 1929, when he made a six-week visit to Britain. Three years earlier, his Battleship Potemkin had created a sensation in Germany and was banned outright in most countries outside Soviet Russia, for fear its impact would incite mutiny and revolution. But it was also admired by all who managed see it, from a young David Selznick starting his career in Hollywood to the British documentary impresario John Grierson, who used a private screening for MPs to extract funding for films to counteract such dangerous propaganda.

Potemkin received its long-delayed British premiere at a glittering private Film Society screening, and everywhere the great and the good wanted to meet its director. Now, a new exhibition drawing on Russian archives probes Eisenstein’s enthusiasm for British history and culture, revealing little-known aspects of his life – and art – beyond the famous films.

Eisenstein’s Anglophilia ran deep. As a privileged child in pre-revolutionary Riga, he learned English from a governess and read all the great Victorian children’s classics. He later insisted that English authors were the first to take children seriously (citing Dickens’ “little Paul Dombey, David Copperfield, Little Dorrit and Nicholas Nickleby”) and also defending the nonsensical invention of Lewis Carroll and Edward Lear, while noting wryly that “infantilism” was not much in fashion in the USSR.

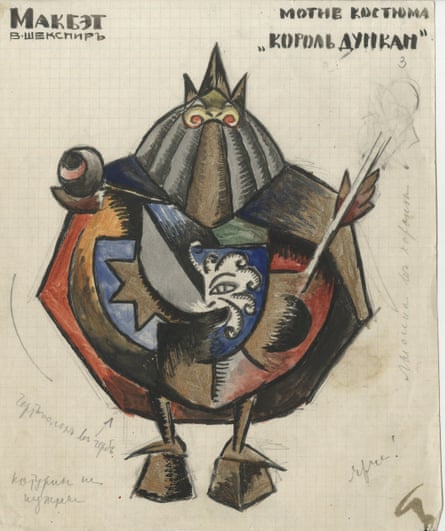

He knew Sherlock Holmes from childhood and the exhibition, at the Gallery for Russian Arts and Design in London, includes his costume designs from the Bakhrushin Theatre Museum for a 1922 stage extravaganza that would have pitted Holmes against the reigning dime-novel detective, Nick Carter, in the early years of Soviet experimental theatre. It seems unlikely that he could have resisted visiting Holmes’s mythic Baker Street when in London, but otherwise he explored the East End from a modest base near Russell Square and gave lectures to would-be film-makers in a room above Foyles bookshop. As late as 1934, he was impatiently ordering the very latest contribution to the legend – Vincent Starrett’s playful mixture of scholarship and whimsy, The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes – from the London bookshop where he was proud to have an account, Zwemmer’s on Charing Cross Road.

Shakespeare was a lifelong passion, as was Ben Jonson, whom he had discovered after buying a copy of Volpone for Aubrey Beardsley’s illustrations. When Eisenstein came to update his famous theory of montage in 1937, he invoked Shakespeare’s “astounding skill” in using short separate episodes of battle in the last acts of Macbeth and Richard III, but also “the image of the dizzy whirl of a fairground” in Jonson’s Bartholomew Fair.

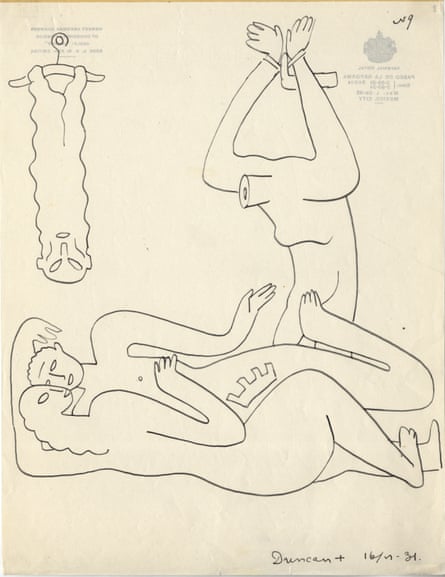

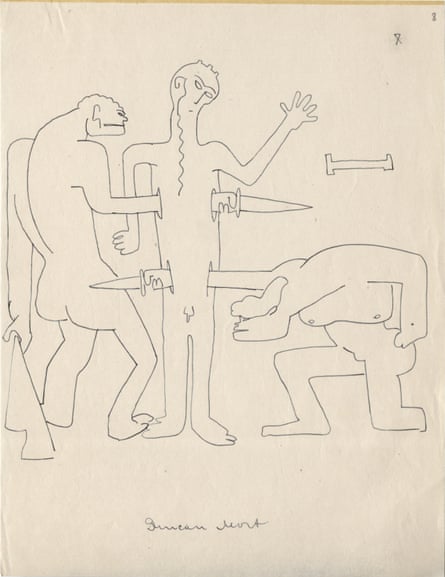

Eisenstein “woke up famous”, as he recalled, because of the worldwide impact of Battleship Potemkin. And this fame – followed by October, which celebrated the 1917 revolution on an epic scale – allowed him to pursue his intellectual and emotional passions to an unusual degree. In Mexico in 1931, trying to complete a sprawling epic about that country’s history, he started to draw in a new and intense way. In just one day, he produced a vast, astonishing cycle of variations on the murder triangle of Macbeth, his wife and King Duncan. Some of the riotously obscene Mexican drawings would help to blacken his reputation with the backer of his Mexican venture, the socialist millionaire Upton Sinclair. But the Duncan death cycle shows Eisenstein as a gifted draughtsman.

Another little-known series of drawings, Thoughts on Music, reveals Eisenstein exploring ideas of visual rhythm with imagery from Alexander Nevsky, the film that restored him to favour in Stalin’s Russia in 1938. Nevsky showed one of ancient Russia’s saintly heroes rallying a peasant army against the fearsome might of the invading Teutonic knights, who are defeated on a frozen lake in a sequence that has influenced countless later screen battles. The film proved a temporary embarrassment when Stalin struck his truce with Hitler in 1939, but after the German invasion began 20 months later, it became a rallying point for all who opposed the Nazi war machine.

Nevsky would have a particular resonance in Britain. After it was shown by the Film Society, BBC television pioneer Dallas Bower used it to train his first cameramen. Transferred to wireless after the outbreak of war, Bower proposed a radio version of Nevsky, and commissioned the poet Louis MacNeice to write the text, while Prokofiev’s score was brought in for a full-scale performance to be conducted by Adrian Boult. With Robert Donat starring as Alexander, and 200 performers and technicians gathered at Bedford School, news came of the Japanese strike at Pearl Harbour that brought the US into the war. The transmission of Alexander Nevsky on 8 December 1941 proved not only a landmark in radio drama, but a first celebration of the grand wartime alliance against fascism.

Bower next pushed the idea of a British equivalent. Why not film Shakespeare’s rousing Henry V in the style of Nevsky? He managed to interest the producer Filippo Del Guidice and Laurence Olivier in the idea. The eventual result was the great Technicolor production of 1944, which borrowed Nevsky’s combination of historical research and stylised realism, culminating in the Battle of Agincourt shot with Irish troops in Eire.

Eisenstein planned an Elizabethan episode for what would be his own last film, Ivan the Terrible. With apparent disregard for the prudishness of Stalin’s Russia, he envisaged that the Russian Tsar would be shown paying court to Elizabeth of England through Moscow’s first ambassador. And his choice of actor for the virgin queen was fellow-director Mikhail Romm, eerily anticipating Sally Potter’s casting of Quentin Crisp as Elizabeth in her 1992 Orlando.

This and many other sequences planned for Ivan were never filmed, and the film’s sombre second part remained banned by Stalin for the rest of Eisenstein’s life. By the time it was finally released during the Khrushchev “thaw” of the late 1950s, Eisenstein’s reputation had entered what might be considered its cold war phase. In Solzhenitsyn’s 1962 novel One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, a convict dismisses him as an “arse-licker” for making films that satisfied Stalin. And later, he would be sidelined by western enthusiasm for Dziga Vertov as a more uncompromising radical, and even later by Andrey Tarkovsky’s antagonism to the very idea of montage.

But in recent years, awareness has grown of Eisenstein’s prodigious output of writings and drawings, and the many unrealised film projects that filled his short life. The challenge today is whether we are ready to grant this polymath another kind of status: as an artist who, like many before him, worked at the court of a tyrant patron; but also as a thinker, who reached back into the prehistory of art and forward into an immersive future cinema in his last writings.

There’s another challenge: imagining the young Sergei, still feeling like “a little boy from Riga”, as he set out to discover the world beyond Russia in 1929, exploring Bloomsbury, Hampton Court, Eton, Windsor and Cambridge in six hectic weeks. We know from his memoirs that these experiences stayed with him (shaping the court scenes of Ivan the Terrible that so spooked Stalin), along with the books that continued to arrive from Zwemmer’s, and the countless English authors and artists who peopled his memory.

Eisenstein may no longer seem as dangerously subversive as he did in 1929. But like another of his heroes and models, Leonardo da Vinci, he remains the nearest cinema has had to a universal genius, with images that even today can still shock and inspire us .

- Unexpected Eisenstein is at GRAD from 17 February to 30 April.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion