John Law was photographing Canary Wharf at night when he was threatened with arrest. The problem, he was told by security guards, was that he was using a tripod. In truth, it was because he was standing on privately owned land.

A Guardian Cities investigation into pseudo-public spaces in London – open areas which look and feel like public space but are actually privately owned and subject to private restrictions – has prompted widespread disquiet and debate among city residents.

Many people got in touch to share their experiences of these spaces, with photographers in particular reporting being frequently told by security guards to stop shooting in ostensibly public spaces, especially if using professional-looking equipment. “Try taking a picture ... and you’ll be accosted pretty quick,” wrote one reader of Tower Place, a pseudo-public space beside the Tower of London tourist attraction.

Another reader, who gave his name as Tim, said he had been told by an “officious security guard type” to stop shooting the CityPoint skyscraper. “Why you shouldn’t take a photo of a building that’s visible from miles away I have no idea,” he said.

As a photographer, being chased off on what 'appears' to be a public street in London, gets on my nerves and becoming more common. 😟

— David Neil Robinson (@DDIGITALMEDIA) July 24, 2017

This happens all over UK: I'm often stopped from working by security informing me 'public' land is actually private. https://t.co/AlRdWH4RrY

— Nick Garnett (@NickGarnettBBC) July 24, 2017

Singling out Canary Wharf, Tom Chambers told the Guardian that privately-owned public spaces, also known as “Pops”, closely resembled a genuinely public space. “It imitates the municipal environment so closely that unless you pay very close attention, it appears to be a space with all the rights and regulations that democracy affords.

“The frightening thing about pseudo-public spaces is that they suit the powerful – people who are not homeless, don’t need to get a message out, don’t need to protest anything and like things as they are.”

One university student, who asked to remain anonymous, said she had found private ownership of space around her university to have complicated issues of access. She relied on her car because of a disability, but the assigned parking bays were some distance from the campus entrance, and behind a barrier that opened only with a call button.

When she made a formal complaint against the university in March, she was told that a senior member of staff would write to the private managers. She also contacted that company herself with suggestions for improvement, but said the owners “just don’t want to know.”

‘Frightening’

One respondent, Stephen, described feeling under constant surveillance when he passed through More London, the privately owned development on the south bank of the Thames. “It’s all very Orwellian – your every move being watched,” he said.

Many readers said they had been spoken to rudely by security guards in pseudo-public spaces. One respondent, Tom Leighton, said he had encountered guards who were poorly trained and applied rules inconsistently. “It’s the insidious nature of their yellow hi-viz jackets that scream: ‘I’m watching you, so don’t do anything I have decided is against the rules’.”

In other respects, readers reported private security cracking down on public drinking. One reader complained of having been moved on by security from a square near Saint Katherine’s Docks, where she and a friend had been enjoying cans of gin and tonic on a sunny day.

A tour guide on Regent’s Canal remembered the entire tour company being barred from entering Camden Market, despite frequenting the area daily, because one employee was a little drunk. “We tried to discuss this, but security guards came and blocked the gate. When we continued to ask for access to a ‘public’ space, a manager came and laughed, saying ‘This is no public space! It’s private, and we can keep out whoever we want’.”

‘Better maintained’

But not everyone was against the spaces, however even those in favour remarked on their homogeneity – “clean and pleasant, but samey and predictable”.

One reader contrasted the “highly controlled” atmosphere of Chiswick Park (“It’s hard to relax, or really unwind”) with Chiswick House, an aristocratic garden turned public space that people shared with “exuberant plant life, wildlife, dog-life – for me, the comparison says it all.”

But there are undoubtedly worse things for a place to be than “sterilised”, to use one reader’s description. A Royal Docks resident who asked to remain anonymous said Pops were “usually better maintained, more pleasant to visit, less prone to vandalism and antisocial behaviour” than the equivalent public spaces.

They gave the example of a park “left to decay” by the Greater London Authority, where large areas had been fenced off due to lack of maintenance and fountains had not worked for over a decade despite being only 20 years old.

Some readers seemed resigned to Pops as a means to an end. One reader, Guy, wrote that while he “despised” them in principle, he had found most to be clean and safe – if “maybe too sanitised”.

“It is often assumed that public space is better run privately – this sadly may be the case in London, due to the councils jettisoning their responsibilities to save cash.” (He added that Bristol and Portsmouth had thriving public spaces: “I assume budgets stretch further outside of the capital.”)

A reader who worked in Convent Garden said that in an area with a high terrorist threat, the presence of private security “in general is appreciated” – though added that police would presumably be more effective in the event of an attack.

The trouble is that we want the amenities the private owner is financing and it's natural they should want provision to be on their terms? https://t.co/RfobuPo5YZ

— Simpaulme (@MorranPaul) July 24, 2017

Expanding by email, Morran took issue with the Conservative councillor Daniel Moylan’s argument that “private landowners have the power to coerce us in what appear to be public streets and squares”.

Appearance, he wrote, was not the issue. “I am no lawyer, but it seems to me there are other ‘public’ places (e.g. churches, ‘public houses’) which we may feel entitled to use, while still recognising that restrictive ‘by-laws’ may apply there.”

That said, he himself had been challenged by private security guards in separate incidents in London and north-west Cambridge, and had “come away slightly shaken”. The latter experience, of being “targeted in a rather bullying fashion ... [for] a few innocent snaps” of new plantings, had inspired a haiku.

Development site.

Nature so obliging – new

Plantings show new growth.Burly, yellow clad

Guard takes my name: ‘Why you take

Pictures? Not allowed!’

Beyond London

Joe Laverty said he had regularly come up against a “clampdown on basic urban freedoms” while practising photography in London, and worried that that was on its way to becoming the norm in his home city of Belfast. “It feels like we’re sleepwalking into the same territory.”

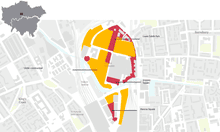

Laverty singled out plans to develop Belfast’s central Cathedral Quarter, of which 12 acres had been bought last year by the English investment company Castlebrooke.

Rebekah McCabe, chair of the Save CQ campaign, said the proposal was still in the pre-planning stages, but as it currently stood half the public Writer’s Square would be lost to new buildings. The developer had also refused to answer questions about the future management of the spaces.

“I think people assume benign intentions and that if it’s well maintained and landscaped, it’s a good thing for the city,” she told the Guardian. “But one of the things we’re trying to talk about is that it’s a real encroachment on civic freedoms. If you don’t know who owns a space, you don’t know the rules of it, and who polices it.”

McCabe gave the example of Victoria Square mall, a commercial space that was also a popular and convenient shortcut through the city. “I have been stopped from wheeling my bike through it, from walking my dog.

“The porousness of being able to move from one end of the city to another is controlled by private security firms, and that’s a problem, because if you follow it through to its possible conclusion, it means that cities become places that are only for a select few.”

Surely @Victoria_Square could be much more child friendly? Spend a fortune there and kids told off again for being on their little scooters.

— Maeve Monaghan (@maevemonaghan) July 23, 2017

Shared spaces were of particular importance to a historically segregated city such as Belfast, but their purpose was being derailed by “middle class ideals”, she said. “What we’re seeing is sharing of space as civic engagement is becoming less important than people being able to shop in the same shopping centre.”

Sumayya Mohamed, an urban geography student in Johannesburg, said public spaces in her city were mostly in gentrified neighbourhoods, and therefore inevitably exclusive. “There is a stark gap between each social class … public space has ended up having different meanings, theoretically and visually, to different people,” she wrote.

Part of the problem many readers identified with Pops was the lack of public disclosure. Dr Andreas Schulze Baing, a lecturer in urban planning at the University of Manchester, tweeted a photo of a sign detailing public rights in Pops in Hamburg.

In Hamburg #hafencity there are signs with detailed regulations of public rights on private open spaces. pic.twitter.com/sHuFRmVseL

— Andreas SchulzeBäing (@baeing) July 24, 2017

But reader Myles Cook’s contribution suggested the solution was not about labelling Pops – but valuing public spaces. His experience of living in Berlin, Munich and Dresden had been “totally at odds” with his time in London, he said. “In every instance, people seemed to use the cities and their public spaces like an extension of their own homes.”

Nowhere was this contrast more marked than in Vienna. “Here, using public space is a natural part of people’s day-to-day lives, and the city government appears intent on ensuring that continues to be the case.”

One of the areas he singled out was Seestadt, a new social housing development with a park and a lake to be enjoyed by the wider public. “Whereas London seems to be reducing the amount of public space, Vienna seems to be doing the opposite, and creating even more.”

- Spotted something missing? Tell us how we can make our map better

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter and Facebook to join the discussion, and explore our archive