There is a familiar rhythm to French politics. President gets elected amid a wave of optimism. President says root and branch reform of the economy will lead to stronger growth and falling unemployment. President fails to deliver the promised transformation. Economy continues to struggle. President gets booted out of office.

In the past 30 years, François Mitterand, Jacques Chirac, Nicolas Sarkozy and François Hollande have won elections for the mainstream parties of the centre left and centre right but France’s economic problems have not been resolved. It says something about how poor performance has been under Hollande that growth of barely more than 1% in 2016 was good by recent standards.

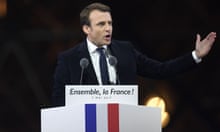

The upshot is that France has lost faith in the old established parties and is increasingly willing to give something new a try. More than 60% of those who voted in the first round of the presidential election voted for self-styled radical outsiders: Marine Le Pen of the radical right; Jean-Luc Mélenchon of the radical left; and Emmanuel Macron of the radical centre.

Assuming the polls are right, Macron will be president in a week’s time. If he loses to Le Pen on 7 May, it will be a bigger surprise than Brexit or Donald Trump’s victory in the US presidential election. Macron will then have to deliver on his promises.

France’s economic performance in recent years has been underwhelming, especially when compared to that of Germany. Fifteen years ago, the eurozone’s two biggest countries enjoyed comparable living standards. Today, Germany’s are almost a fifth higher than those in France. Likewise, at the time when euro notes and coins were introduced in 2002, French and German unemployment rates were both around 8%. Today, Germany’s unemployment rate has dropped below 4% while French unemployment is close to 10%.

Youth unemployment is a particular problem. Almost one in four of those aged under 25 are out of work, a much higher rate than in Germany. Hollande has had some success increasing the number of people in training and he forced through legislation last year making hiring and firing easier. But more than 85% of employment growth last year was for temporary jobs, and the vast majority of those hired were on contracts of less than a month.

These are not new problems. From the mid-1990s to the start of the financial crisis in 2007, only Italy among the rich members of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development has grown less quickly than France. Since the crash, France’s recovery has lagged well behind the US, the UK and Germany.

It is not all bad news. France has good productivity, a strong industrial base and levels of inequality similar to those in Germany and the Netherlands, but much lower than in the UK and the US. The employment rate for prime-aged workers – 35- to 54-year-olds – is higher than it is in the US.

Even so, France’s poor economic record has left it with an inferiority complex when it comes to Germany. In part, France’s championing of the single currency in the 1990s was due to its belief that monetary union would dilute Germany’s influence over European economic policy. Germany was always suspicious of the French claim that the single currency would be the catalyst for economic convergence, and so it has proved. The divergence in economic performance has left France in a clearly subservient role and Germany wary of any further integration that will involve it writing blank cheques to the rest of the eurozone. Berlin has grown impatient with the failure of French politicians to deliver on the reforms they have promised. As a result, it is no longer a partnership of equals. Angela Merkel never took Hollande all that seriously.

According to Charles Grant, director of the Centre for European Reform thinktank, Macron wants two things from Germany. Firstly, he wants Berlin to agree to reflate its domestic economy, thereby helping not just French exporters but those of other EU countries. Secondly, he wants to complete the monetary union project by having a eurozone budget managed by a eurozone parliament and a eurozone finance minister.

It would certainly help the other members of the single currency if Germany invested and consumed more. There is also something intrinsically unstable about the euro in its current incomplete form.

But getting the Germans to agree to Macron’s proposed changes is not going to be easy. In part, that’s because reforms of the labour market will run into stiff opposition and – if history is any guide – will be watered down. But even if Macron does push all his changes through, there is no guarantee that growth will accelerate and unemployment will plummet.

And that’s because the assumption is that all France’s problems stem from structural rigidity and the lack of labour market flexibility rather than from inadequate demand. The classic neo-liberal diagnosis is that the French state is too big and needs to be pared back through significant cuts in spending. Likewise, the French unions are too powerful and the unemployed need to price themselves into jobs by working harder for lower wages.

This has been the standard explanation of France’s economic woes ever since the abandonment of Keynesianism in the early 1980s. The abiding economic orthodoxy has held that low inflation should be the sole aim of macro-economic policy and should be achieved through control of the money supply; that fiscal policy - changes to tax and spending - is ineffective; and that the economy is a self-adjusting mechanism that will revert to full employment provided prices and wages are flexible.

France, in other words, was not giving up anything of real value when it joined the single currency because all that was required was for the European Central Bank to keep inflation low and for politicians in Paris to embark on meaningful structural reform.

The Keynesian take on France, by contrast, would be that adjustment to shocks tends not to be automatic but comes through the use of all the main economic levers: interest rates, the exchange rate and fiscal policy. The failure to deploy all these weapons explains why growth in the 12 original members of the eurozone averaged 3.4% a year in the 1970s and 0.1% between 2009 and 2015.

Seen from this perspective, Macron does not offer radical centrism but more of the same. By seeing France’s problems as stemming from a lack of supply-side reform rather than from a shortage of demand, he is setting himself up to fail. The difference is that if Macron fails to deliver on his promises, the Front National will be able to mount an even stronger challenge for the presidency in 2022 than it has this time. That’s why the stakes for Macron are so high.