Why don't third parties succeed in US? Maybe it’s the law.

Loading...

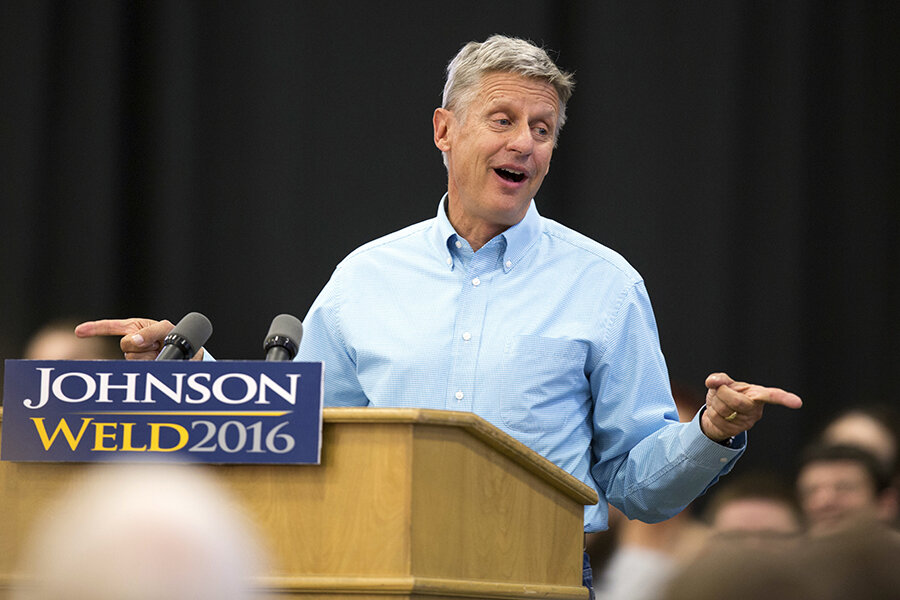

When Democrat Hillary Clinton and Republican Donald Trump walk onstage for tonight’s presidential debate, why will they be alone? Why won’t Libertarian Gary Johnson and the Green Party’s Jill Stein be there?

The short answer is that Mr. Johnson and Ms. Stein did not clear an arbitrary polling threshold. Last October, the Commission on Presidential Debates announced that only candidates polling 15 percent or more in an average of major surveys would be allowed on the debate stage. Johnson is drawing around 7 percent at the moment, according to RealClearPolitics. Stein is down around 2 percent.

The long answer – which addresses why third parties have a hard time muscling into the top tier of US politics – may be that it’s the law. Duverger’s law.

Named for French political scientist Maurice Duverger, Duverger’s law is more of a theory than an actual, you know, statute. It holds that any democratic country with single-member legislative districts and winner-take-all voting tends to favor a two-party system.

That’s because many voters don’t want to waste their ballot, and thus gravitate toward a legislative candidate they think has a chance to win. Third-party candidates have a hard time building enough of a following to actually win a congressional or state legislative seat, in this theory. And without a grass-roots base of elected officials, third-party candidates who aren’t already famous have a very difficult time building momentum.

The US has had notable third-party candidates in recent years. Ross Perot won 19 percent of the popular vote in 1992. Ralph Nader’s 3 percent of the vote in 2000 might have been just enough to cost Al Gore the election.

And Duverger’s law is far from a perfect explanation of the real world. Critics point out counter-examples, such as Britain, where single-member winner-take-all districts have produced multiple-party systems. State ballot access laws, raw partisanship, and other institutional factors also contribute to third-party struggles.

Still, Duverger’s proposition inspires wide respect in academia. “In political science, this is about as close as we get to a law,” wrote Stanford University political scientist Anna Grzymala-Busse in a 2014 remembrance of the French scholar.

Are there implications here for the 2016 election? Well, it’s possible that as November approaches, Johnson and Stein’s vote share will further dwindle. Some of their backers will decide that a protest vote isn’t as important as actually influencing the outcome. Many aren’t Libertarians or Greens per se, but Republicans and Democrats who won’t, or haven’t yet, committed to Clinton or Trump.

According to polls, Stein’s sliver seems more committed, but for many Green voters, Clinton is their second choice. Johnson draws support more from disaffected members of both parties. It’s not clear who would benefit more if some of the Libertarian’s current supporters abandon him.

Yes, the numbers here are small. The net result of a shakeout among current third-party voters might be only a few percentage points for one big party candidate or another. But the distance between Clinton and Trump is paper-thin at the moment. A percentage point or two could make all the difference on Nov. 8.