China's Unsettling Stock Market Collapse

As the world frets over Greece, a separate crisis looms in China.

This summer has not been calm for the global economy. In Europe, a Greek referendum this Sunday may determine whether the country will remain in the eurozone. In North America, meanwhile, the governor of Puerto Rico claimed last week that the island would be unable to pay off its debts, raising unsettling questions about the health of American municipal bonds.

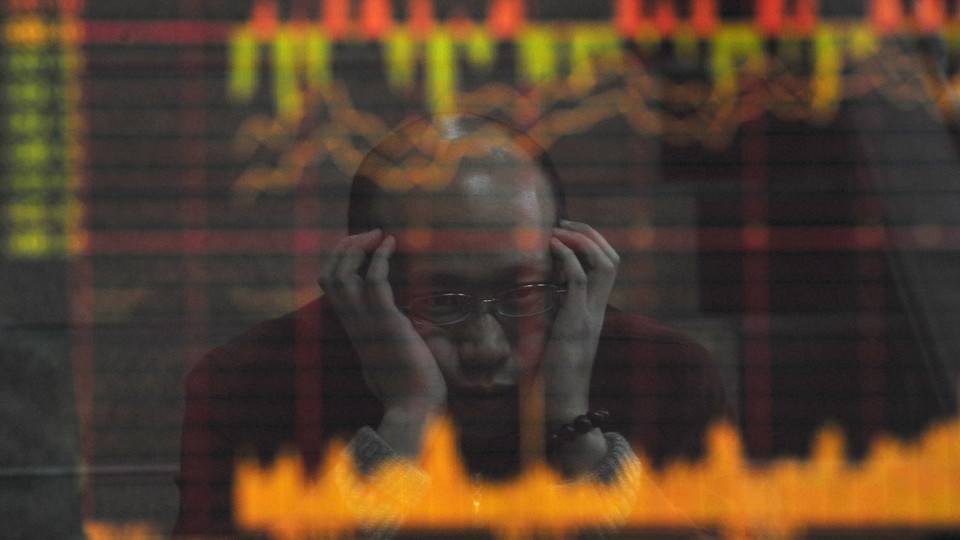

But the season’s biggest economic crisis may be occurring in Asia, where shares in China’s two major stock exchanges have nosedived in the past three weeks. Since June 12, the Shanghai stock exchange has lost 24 percent of its value, while the damage in the southern city of Shenzhen has been even greater at 30 percent. The tumble has already wiped out more than $2.4 trillion in wealth—a figure roughly 10 times the size of Greece’s economy.

Skittish at the prospect of further losses, the Chinese government has taken action. On Saturday, the country’s largest brokerage firms agreed to establish a fund worth 120 billion yuan ($19.4 billion) to buy shares in the largest companies listed in the index. Beijing has also lowered interest rates, relaxed restrictions on buying stocks with borrowed money, and imposed a moratorium on initial public offerings. The country has even relied on propaganda to encourage the public to hold onto their shares for patriotic reasons.

The recent fall in the Chinese stock market followed an extraordinary bull period in which the Shanghai composite grew by 149 percent this year through June 12. The boom was fueled by retail punters relatively new to investing—according to the Financial Times, more than 12 million new accounts were opened on the stock exchange in May alone. Once dominated by elites, the stock market increasingly has become a vehicle for China’s emerging middle class. Two thirds of households who opened accounts in the first quarter of 2015 didn’t even finish high school. Equity market fever has spread to China’s universities, where 31 percent of the country’s college students have invested in a stock. Three quarters of them used money provided by their parents.

In recent years, Chinese people have generally plowed their excess savings into housing, but the uneven performance of the real estate market has spurred interest in other vehicles for domestic investment. (Because of strict capital controls, it’s very difficult for most Chinese people to move money out of the country.) Increasingly, more have turned to the stock market. According to Bloomberg, over 90 million people in China have invested in equities—a number greater than the total membership in the Chinese Communist Party.

The recent dip in prices, then, affects the fortunes of a large number of people. Should those outside of China worry about it?

Perhaps not. For a heavily integrated global economy that’s now the world’s second largest, China’s stock markets are quite isolated. Foreign investors hold only two percent of all Chinese equities, and equities account for only around 5 percent of overall financing. China’s aggregate bank deposits—a staggering $21 trillion—also provides a buffer against major market fluctuations. And the long bull run that preceded June’s swoon has not faded entirely: The Shanghai Composite is still up 20 percent since January 1.

Nevertheless, such volatility in the world’s second largest equity market (by market capitalization) raises questions about the overall health of China’s economy. GDP grew by 7 percent in the first quarter of 2015, its weakest mark in six years, and stimulus measures adopted by the government have yet to reverse this slide. According to Ira Kalish, Chief Economist at Deloitte, China’s slowdown has already had consequences beyond its borders.

“Already, the halving of China’s growth has wreaked havoc with global commodity markets and has negatively influenced growth in those East Asian economies that are a vital part of China’s manufacturing supply chain,” he wrote in ChinaFile. “It could be argued that the imbalances in China’s economy thus represent more of a risk to the global economy than the current and much discussed situation in Greece.”