The ball looked like trouble the moment it came off Justin Turner's bat. With two outs in the ninth inning of a one-run game between the Atlanta Braves and New York Mets in July 2013, the tying and winning runs were on base. Braves center fielder Jason Heyward knew they would be going on contact, and they were—they took off as the ball was lined toward the gap in left-center. The Braves, so close to victory, were now seconds from defeat—until Heyward rushed across the outfield, dove and caught the ball before it could kiss the grass. Just like that, he had secured the win for the Braves, and a place in the highlight reels for himself.

David O'Brien, of The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, wrote that Heyward "[raced] over from the right-center gap," then "dove and fully extended his big body to catch the ball inches from the ground." D.J. Short, a writer at NBC Sports's Hardball Talk blog, credited Heyward for "[getting] on his horse to make an all-out diving catch." The Associated Press channeled Theodor Geisel by suggesting that Heyward "made a flat out dive for the drive."

At the MIT Sloan Sports Analytics Conference in March, the catch was described in a very different language: Turner's batted ball traveled at 88 miles per hour toward the gap; split the two nearest outfielders, stationed some 81 and 83 feet away; and hung in the air for four seconds. Heyward caught the ball because his first movement came three-hundredths of a second quicker than teammate Reed Johnson's, and his top speed was three miles per hour faster than Johnson's. But the key to the play was an almost perfect route to the ball: He traveled a path that was 97 percent true to a straight line.

This detailed breakdown of Heyward's Web Gem is a glimpse of where the sport is headed. Big data is about to change how baseball is managed, analyzed and consumed.

The company responsible for the futuristic presentation, Major League Baseball Advanced Media (MLBAM), is the same in-house outfit responsible for applications like MLB.tv and MLB At Bat. Their new toy, dubbed Statcast, tracks every player on the field through a combination of radar technology (supplied by Trackman) and cameras (supplied by ChyronHego), stationed about 15 yards apart (one behind home plate and one down the third base line) so as to emulate the depth perception of the human eye. Although Statcast is active in just three parks for the 2014 season—Citi Field in New York, Target Field in Minneapolis and Miller Park in Milwaukee—the plan is to install the system in all big-league parks before next season.

Because Statcast is a league-wide initiative, every team is receiving the data. This makes Statcast more comparable to PITCHf/x—a MLBAM product that tracks every pitch for the sake of granular analysis—than to subscription-based offerings, like Bloomberg Sports, that provide teams with video and scouting services for a fee. "Other sports have had success with their ventures into digital tracking," says Harry Pavlidis, director of technology at Baseball Prospectus, a website that specializes in advanced analysis. "For a major analytical move forward, it is in the league's best interest to make sure the rising tide lifts all 30 ships, not just the rich ones."

The National Basketball Association believed that an all-in effort was in its best interest when it ventured into the player-tracking world prior to last season. About half the NBA's teams had purchased the necessary equipment—cameras from STATS LLC. that reportedly cost $100,000 a season—when the league decided to foot the bill for the laggards in the name of leveling the statistical playing field. Although MLB has not prevented teams from proceeding on their own when it comes to other advances in data collection—for instance, installing PITCHf/x-like systems at their minor league parks—baseball, like basketball, opted for a united approach toward the new world of player-tracking technology.

Why a joint effort of 30 teams who are competing against each other? If the technology weren't available in all 30 parks—and some owners would surely balk at paying for the technology—the data would have gaps in it. The success of such a system relies on its promise to capture everything, and MLB's decision to take charge ensures that it will—and that it will be available to every team. The application of the data, meanwhile, will remain team-by-team decision.

Another incentive for the league—particularly in the face of rising salaries—is an improved understanding of player value, particularly on the defensive end, where teams have focused more attention in the past few years. Defensive shifts, once only employed by the wonkiest teams, have become a league-wide staple thanks to advances in batted-ball data. The problem is, shifts or not, evaluating glove work remains difficult, as most teams rely on some combination of scouting reports, play-by-play data and manual charting. Statcast offers something better: a way to focus on a player's defensive attributes—his reaction time, range, route efficiency and so on—rather than his results, which are influenced by too many independent variables to list. This potential has excited many outside the industry (especially with the promise that the data will be made public) and even more within.

T.J. Barra, manager of baseball information and minor league operations for the Mets, has firsthand experience with the new data—his team plays at one of the three pilot stadiums. He compared himself to a kid in a candy store, telling Newsweek in an email, "As with PITCHf/x, HITf/x and Trackman data before [them], we are going to learn new things. There will be players who thrive in areas we have not yet fully been able to quantify; these will become the new undervalued players."

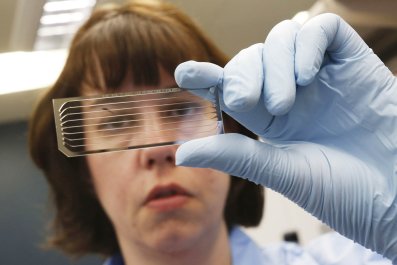

Too much data, like too much candy, has its negatives. Statcast will reportedly create more than seven terabytes of data—more than 7,340,032 megabytes (the equivalent of 2,446,677 three-minute song MP3s—per game. Parsing the files will prove problematic logistically, and that's before entering the murky world of data analytics, complete with support vector machines, clustering, algorithms—and practitioners who view their field as half art, half hard science. "This might be the first 'big data' problem in baseball," Barra says.

Barra estimates that only a dozen teams have the infrastructure to fully handle all that data. The needs go beyond hardware. "Understanding this data will require a dedicated analyst or team of analysts, who can figure out how to maximize this data as both an evaluation and coaching tool," he explains. "These are new concepts and new metrics, which need to be explored. Without sufficient resources, teams could be left behind."

At least one team is ensuring it won't be left behind. The Economist reported in March that an unnamed club had purchased a Cray supercomputer, priced at a minimum of $500,000—about the same as the minimum salary for a big-league player. The team, yet to be identified, is in essence paying for a 26th player. All in order to reap the benefits of big data.

"It's like the Wild West," Barra says. "There is so much to be discovered."

The only negative to come from all the new technology could be the death of the hobbyist. An important consideration, because some hobbyists have done research that changed how people inside and outside the industry approach the game. For example, Mike Fast was working as a physicist when he used PITCHf/x data to confirm the long-held suspicion that catchers influence how umpires call balls and strikes. Fast is now employed by the Houston Astros. Because the new data are so unwieldy, the barrier to entry so high, only select outsiders will possess the computing strength and wits to scale the wall. In time, someone might make a discovery that eluded the industry. Otherwise, the real advances—those that change how teams are built and how strategies are employed—will happen behind closed doors.

For the layman who has neither a supercomputer nor the interest in dissecting the game's data, all the hoopla seems a bit much. That might not be the case for long. MLBAM has posted videos throughout the season on the league website, outlining just how Statcast could be used as seasoning on otherwise stale television broadcasts. If those demos are any indication, MLB broadcasts are soon going to be very cool for stats junkies.

In fact, it may soon be the case that the tired language used to describe Heyward's catch last summer will become a thing of the past, replaced by words that exhibit the same level of precision as his line of attack as he chases a fly ball.