Diceware is a well-known decades-old system for coming up with passwords. It involves rolling actual six-sided dice as a way to generate truly random numbers that are matched to a long list of English words. Those words are then combined into a non-sensical string ("ample banal bias delta gist latex") that exhibits true randomness and is therefore difficult to crack. The trick, though, is that these passphrases prove relatively easy for humans to memorize.

"This whole concept of making your own passwords and being super secure and stuff, I don’t think my friends understand that, but I think it’s cool," Modi told Ars by phone.

Modi is no ordinary sixth-grader, either. She’s the daughter of Julia Angwin, a veteran privacy-minded journalist at ProPublica and author of Dragnet Nation.

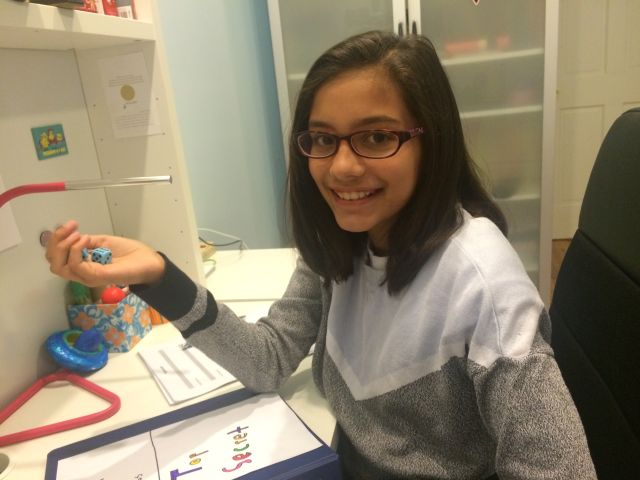

As part of her research for the book, Angwin employed her daughter to generate Diceware passphrases, and Modi had the idea to turn it into a small business. She began accompanying her mother on various book-related events and selling passwords that she generated on the spot—dice and all. But in-person sales were slow.

"I wanted to make it a public thing because I wasn’t getting very much money," she said. "I thought it would be fun to have my own website."

Each time an order comes in, Modi rolls physical dice and looks up the words in a printed copy of the Diceware word list. She writes—by hand—the corresponding password string onto a piece of paper and sends it by postal mail to the customer. (Full disclosure: I ordered two.)

If she kept busy at it full-time, Modi would be raking in about $12 per hour—fully one-third more than New York state’s $8.75 minimum wage, which is set to go up to $9.00 on December 31, 2015. As of now, she said she’s sold "around 30" in total, including in-person sales.

Modi admitted that she’s unique among her circle of friends, whom she says not only pick simple passwords for their social media accounts but also routinely share them with each other.

"I think [good passwords are] important. Now we have such good computers, people can hack into anything so much more quickly," she said. "We have so much more on our social media. We post a lot more social media—when people hack into that it’s not really sad, but when people [try to] hack into your bank account or your e-mail, it’s really important to have a strong password. We’re all on the Internet now."

Crafting passwords the old-fashioned way

When she’s not studying or making Diceware passwords, Modi spends her time doing gymnastics and dancing. As she grows up, she may have a future in cryptography and operational security. "I think it would be really cool to learn more about digital security," she said. "I think it would be really cool to learn more about hacking."

Plus, she understands a crucial security concept about passwords that most adults do not. "If you just make one up," she told us, "it’s not going to be a very good one."

Remember what Edward Snowden said in his initial e-mail to Laura Poitras: "Please confirm that no one has ever had a copy of your private key and that it uses a strong passphrase. Assume your adversary is capable of one trillion guesses per second."

Indeed, Micah Lee, the technologist for The Intercept, who has written extensively about Diceware passphrases, is impressed.

"This is one of the great things about high-entropy passphrases, that sixth graders can easily grasp the concept and memorize them," he told Ars by e-mail. "The math is very simple. Even if you don’t understand how to use logarithms to calculate how many bits of entropy your passphrase is, you can tell that each word you add to your passphrase, out of a stack of paper worth of words, makes it exponentially less guessable, but it’s still not very hard to memorize."

And what does the creator of Diceware himself make of all of this?

"I am tickled to hear this, and no, I haven’t heard of anything like it before," Arnold Reinold told Ars.

"Obviously from a security perspective it is much better to generate your own Diceware passphrase in private, but it is unlikely she is working for the bad guys, and any effort to publicize the importance of strong passwords is for the good," he continued. "I just hope she isn’t sending the generated passphrases to her customers by e-mail or storing them on her computer. I wish her well."

Of course, she’s got those concerns covered.

"People are worried that I will take your passwords, but in reality I won’t be able to remember them," she told Ars. "But I don’t store them on any computer anywhere. As far as I know there is only one copy of your password."

As she reminds customers on her website: "The passwords are sent by US Postal Mail which cannot be opened by the government without a search warrant."

reader comments

261