During the period he refers to as his “glory years”, Damien Hirst had a favourite gag. He would pull his foreskin through a hole in his pocket, then exclaim in mock alarm: “What’s that?” “People would go, ‘You’ve got some chewing gum on your trousers.’ They would touch it and go, ‘What the fuck?’” he said, smirking. He played this trick on drinking buddies and he played it on complete strangers. He particularly enjoyed targeting self-important art world types. Hirst recently turned 50, and these days he appears to be almost fully house-trained. He still has the swagger, leather jacket and T-shirt wardrobe of a rock star, and his mobile phone is loaded with eye-poppingly deviant film clips that he collects for his amusement and often shares; but he also now does yoga three times a week, and stopped flashing when he gave up drink and drugs almost nine years ago.

Britain’s most famous living artist continues to stir controversy, although he is more likely to be excoriated for the failings of the national culture than lauded as a national treasure. Guardians of “real art” and highbrow defenders of the avant garde routinely nestle together under the same duvet, shocked not so much by the paintings and sculptures and installations he churns out at an extraordinary rate as by his refusal to accept that the time has come to keep his creations, like his penis, decently out of sight.

But it’s worth taking note of what Hirst does because he is an agent of change. He has always been entrepreneurial, prolific and populist – qualities that, in tandem with his practice of employing technicians to realise the bulk of his output, challenge ideas about authenticity. And his latest venture may prove the most startling thing he has ever done.

In April, the floor of his office at the Marylebone headquarters of his company, Science Ltd, was strewn with models of a gallery, each hung with tiny replicas – Francis Bacons, John Bellanys, Andy Warhols, Banksys – like toys for a super-rich kid which, in a way, they were. Hirst looked down on the world he was creating and played with its possibilities. He was excited, talking fast, grizzled but boyish in his enthusiasms. He has a face that can move from cherubic to demonic and back again when he is at his most animated, and this project has obsessed him for years. He was plotting a series of exhibitions at the Newport Street Gallery in Lambeth, south London. He has spent £25m to build the facility, where he will curate exhibitions assembled from his own art collection. For the gallery’s opening show this September, he has chosen the British abstract painter John Hoyland, a prodigious talent who never quite enjoyed the recognition he expected or deserved.

It was Hoyland who, in 1997, sounded a rallying cry against the so-called Young British Artists, and Hirst in particular – objecting furiously when the Royal Academy announced plans to put on Sensation, an exhibition of works from Charles Saatchi’s collection of YBA pieces. “Artists should not farm their work out,” he said. “I hear that [Hirst] has lots of people working on his spin paintings. I can’t see how you can have humanity in your work if you do that. Art is a seismograph of the human being. You have to be hands-on.”

Like the target of his complaint, Hoyland once appeared transgressive, bright and acerbic. He was the youngest participant in Situation, an exhibition of abstract paintings by British artists that flustered the art establishment in 1960. Hoyland got his own solo turn at the Whitechapel Gallery seven years later, but by the time of Sensation, his star had been eclipsed by conceptual and pop artists.

Now Hirst, too, has reached an uncomfortable stage in his career, embedded in the establishment he once goaded. On past performance, he might be expected to try even harder to shock, to prove his relevance. Instead, by founding Newport Street, he is doing something far more likely to shore up his status and secure his legacy. In promoting his own view of contemporary art through the medium of a big, public gallery, he is testing his power to shape tastes and markets, and his ability to exert control.

Curating was Hirst’s first talent, and his most consistent. The shows he put on at the start of his career managed to generate a level of excitement not always matched by acclaim for his work. In 1988, he reset the course of British art with the exhibition Freeze, held in an empty Port Authority warehouse in London’s Docklands. The three-part show helped to launch Hirst’s friends and contemporaries, including Mat Collishaw, Angus Fairhurst, Anya Gallaccio, Gary Hume, Michael Landy, Abigail Lane, Sarah Lucas and Fiona Rae. In the push to find a warehouse space, assemble the artists and install their pieces, Hirst left himself little time to focus on his own work, dashing off 81 small boxes, which he then positioned so high that many visitors missed them altogether. He also painted his first spot paintings, straight on to a wall. Collectors and galleries nosed around many of the other participants, but not Hirst.

More than a quarter of a century later, he is seeking to reconcile the conflicts his intervention set in train, in art and in his own life, by returning to curating. One outcome may be more controversy – over the impact of Newport Street on a rare pocket of inner London that has largely resisted gentrification, and about his motivations in establishing the new, free-to-enter gallery. His apparent generosity is likely to be balanced by the increased value of the art shown there, which he of course owns. But to assume that Hirst’s greatest driver is money is to overlook his passion for art, and his compulsion to collect it.

Hirst bought from his contemporaries before he could afford it or they had made much of a mark, and it wasn’t just with a view to a profit; he kept much of what he acquired. Fiona Rae remembers Hirst, as an impoverished undergraduate in the late 1980s, forming a consortium with two other people to buy three of her paintings for £1,000. “That felt like a fortune in those days,” she said in May, sitting amid a solo show of her latest work at the Timothy Taylor Gallery in Mayfair.

Hirst was born in Bristol and brought up in Leeds, and his home life was reasonably comfortable until the breakdown of his mother’s marriage to his stepfather, a mechanic, when he was 12. The disruption to Hirst’s home life triggered a short career in petty crime. “I went into the art lesson once at school, and the police were there doing fingerprints on the windows, because I’d broken in the night before and nicked stuff – paper, pens, pencils, all that kind of stuff – and I remember thinking: ‘Fuck, I didn’t wear gloves.’” Soon after that he moved to London, aiming for art college, and was accused of carrying out a chequebook fraud with a friend. “I got a criminal record for burglary and shoplifting, and that was the final straw. I’d have probably got two years or something. He went to Brixton, and did like three months, and it was his first offence. I just kept denying it, and I went to court three times, denied it, and eventually they dropped the charges against me and I was like: ‘Thank fuck.’ And then after that I didn’t do anything bad again.” A few months later, he started at Goldsmiths.

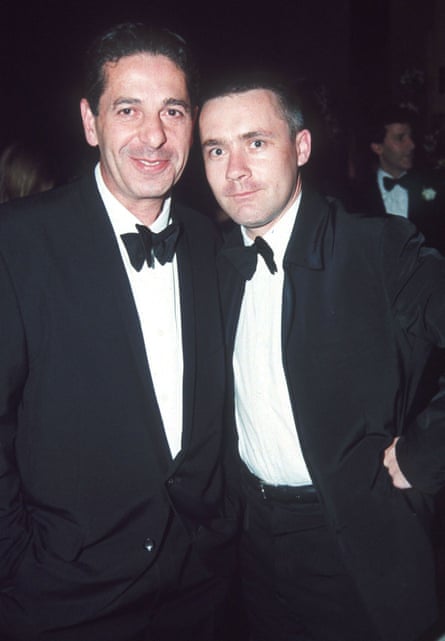

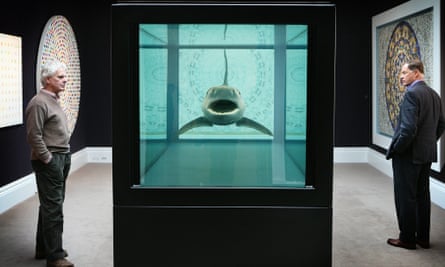

Even then, his vision was expansive. He favoured industrial buildings for exhibiting over typically cramped British galleries. Museums, he believed, were only interested in artists who were dead. “He didn’t wait for permission from institutions,” says Iwona Blazwick, director of the Whitechapel Gallery, who in 1991 put on Hirst’s solo show, Internal Affairs, at the ICA. Hirst had learned some of his tricks from an early advocate, Charles Saatchi. The advertising magnate opened a gallery in a disused paint factory on Boundary Road in St John’s Wood in west London, in 1985, to display his private collection. Hirst and his friends visited, to share in Saatchi’s passion for American artists including Carl Andre, Donald Judd, Frank Stella and Cy Twombly, then reaped the benefits after Saatchi came to Freeze and started buying and showing life-changing quantities of their own work. Saatchi put up the £50,000 for Hirst to manufacture his first shark suspended in formaldehyde, titled The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, in 1991, and for a decade Hirst and Saatchi enjoyed a symbiotic relationship, each boosting the other’s reputation. Then came a rupture that has never fully healed. “He only recognises art with his wallet,” Hirst said after Saatchi offloaded most of his Hirsts in a move that not only offended the artist but threatened to depress the market for his work. A US hedge-fund billionaire called Steven Cohen bought the shark.

Hirst won’t go into the details of the feud, but says the relationship has improved; they are not in regular touch, but Saatchi has agreed to speak to James Fox, the writer helping Hirst with his autobiography. (Last year Hirst signed a deal for the memoir with Penguin, reportedly for a six-figure sum.) After his rackety childhood, Hirst’s relationship with Saatchi appears to have something of a father-son dynamic: a closeness followed by a breach, and then a rapprochement on changed terms; rebellion and imitation.

“I’ve always wanted a gallery like Saatchi, the original Boundary Road,” said Hirst, gazing out across London from a balcony high on the facade of Newport Street Gallery. With 3,438 sq m rendered by architects Caruso St John into six exhibition spaces, offices, store rooms, a shop and a restaurant, Newport Street is bigger than Boundary Road. Hirst is overseeing every detail of this universe, down to the restaurant menus. There is no place for a big-name chef. “All chefs are cunts,” Hirst declared, “like artists.”

There’s a walk-in refrigerator at Chalford Place, the home Hirst sometimes uses when he’s working at the older and smaller of his two Gloucestershire studio complexes. In this context, the fridge seems sinister, yawning emptily, but big enough for corpses. Chalford Place is one of its owner’s most fascinating creations; unseen and still unfinished, an immersive Disneyland of death. Potato famine-era gravestones (imported from an Irish salvage company) line the floors and showers, the wood panelling is decorated with skeletons and butterflies, and the handles on a chest of drawers are casts of vertebrae. A funereal ground-floor bedroom is encrusted, floors and ceiling, with amethyst. The books in the bookshelves are united by one feature: they all have the word “death” in the title. Everywhere there are skulls – real, carved, stained-glass and painted.

Like much that Hirst produces – indeed, like Hirst himself – the house is a strange mixture of the compelling and the banal. Death has been the preoccupation of much of his work, but it’s often hard to tell whether he’s engaging with the idea or diminishing its power by turning it into a motif. His butterflies are drowning in paint. In his famous 1990 work A Thousand Years, flies breed in one half of a large glass cabinet; their dead bodies drift ever deeper along the edges of the installation. And when For the Love of God – Hirst’s platinum skull studded with diamonds and baring human teeth – came on to the market in 2007, it took the breath away less as a memento mori than with its supposed price tag of £50m. He was part of a consortium that bought the work, a transaction that helped to maintain the market value of all his output.

People close to Hirst seem just as confused about what drives him as he is himself. “He’s a hooligan and aesthete,” said Mat Collishaw. “This is not a normal combination of characteristics.” His halting attempts to talk about hitting 50 convey a real anxiety. “If you’re going to get hit by a bus on the way to chemo, you just don’t know where [death] is coming from,” he said, sipping from a mug of redbush tea. Yoga and his healthy lifestyle might help him to live longer, or just to die better. “You lose your grip anyway. You lose your grip before you die, I think that’s the problem. So I guess it’s how to embrace it in some way.”

Hirst initially resisted the idea of an autobiography because he saw it as an end-of-life activity. He is now embarked on the process, but publication isn’t expected any time soon. He has a lot on his plate – as well as Newport Street, he has elaborate, if secret, plans to unveil new work in 2017 – and the process of reconstructing his past has also been slowed by his own deficiencies as a witness to his own life. Hirst says Fox – who helped Keith Richards to fill in the gaps in his memory that are the inevitable consequence of a life in rock’n’roll – has been plucking anecdotes gleaned from interviews with other sources to prompt Hirst to remember his own past. But there’s something else a person who successfully obliterates whole segments of his life may find difficult to recall: the reasons for doing so.

Collishaw advanced a plausible theory about what drew Hirst to art, which happens to provide one reason why Hirst may have found drugs and alcohol so tempting: “His mind is going a million miles an hour, and maybe the thing with the artwork is that it’s something you just concentrate on for a few moments, and suddenly you’re transported into this other realm.”

Hirst said he remembers gazing awestruck at a blue painting by John Hoyland in Leeds City Art Gallery as a schoolboy. Little in his family background might have been expected to tempt him into the gallery in the first place, but art seems to have brought him much-needed moments of calm. Then it became the thing that ostensibly drove him faster. During the boom years of the late 1990s and into the next decade, Hirst was in perpetual motion. He expanded his studio system, started a publishing company, launched shops, purchased a string of properties in the UK, Mexico and Thailand – including a money pit of a stately home in Gloucestershire called Toddington Manor – and still found time to carouse. Such feverish activity looks like the behaviour of someone for whom fears of mortality are visceral. Making skulls and hacking up dead cows kept death at a distance. “I deal with death in art, not in life,” he said. “It’s like, in art, everything is a celebration. Because if you really think about death, it makes you inactive.” He added: “For those 20 years, I was totally celebrating. And the work was celebrating. And it was like I was immortal.”

Then, by degrees, he wasn’t. In place of the outgoing, expansive pleasure-seeker Rae remembers from Goldsmiths – “very funny, always up for fun and doing outrageous things, I couldn’t keep up really. You’d get a phone call from Damien saying he’s in a skip, come and join him for a drink” – a sadder incarnation developed.

Drinking friends such as the musicians Joe Strummer and Alex James, and the actor Keith Allen, warned Hirst he had a problem. “You get to a point at the end of it where people just go, ‘Ignore him,’” Hirst recalled, still clutching his redbush. “I remember Joe going: ‘Ignore him. He’ll go to bed.’ And you’re just thinking: ‘Why does that happen?’ And you think: ‘No!’ But you do know. You’re spitting at people because you’re so drunk, drooling, you’re just unpleasant.”

Despite several false starts, and without the help of a 12-step programme, he finally cleaned up in 2006. His relationship with Maia Norman, the mother of his three children, couldn’t weather the transformation. Most recovering addicts face the daunting task of taking greater responsibility for themselves; Hirst found himself at the apex of an empire employing between 120 and 160 people – at a high-water mark ahead of a 2012 Tate retrospective of his work, staff numbers soared to 250 – with many more businesses in some way dependent on his continued high rate of output. “You have to keep this fucking thing, this machine, going,” says Hirst’s friend, the artist and writer Danny Moynihan. “He seems to wear it quite lightly and everything continues, but it’s a machine.”

The machine used to be dirty, a scraggle of improvised studio spaces. There was one under railway arches that everyone, including Hirst, referred to as the “pill mines”, a sweat shop – albeit one offering decent wages – of recent art graduates fashioning the pills to place in his medicine cabinets, or fulfilling similarly fiddly and repetitive jobs to create some of the other Hirst products. “Sanding down pills, day in, day out,” Hirst said. “Funny when you go to your own studio and feel guilty. That’s why I used to lay on these huge parties. I remember feeling guilty for those people. What have I done? I’ve created a monster. Back to the pub.”

The majority of Hirst’s studio employees now toil in the pristine, high-security confines of a vast complex at Dudbridge in Gloucestershire. Hirst said he drew inspiration from Andy Warhol’s Factory, but if Warhol’s studio was part production line, part salon, Hirst’s main studio is all about industry.

On a chill spring day, everyone wore matching Science Ltd T-shirts, wordless and focused, the silence punctured by the scrape of a chair on concrete and rock music, played not as Hirst would listen to it, but quietly in the background. Different sections of the studio are dedicated to different strands of art carrying the Hirst imprimatur: the butterflies; paintings mixing up corporate logos with political emblems; landscapes fashioned from razor blades; photorealist “fact” paintings of cancer cells; medicine cabinets and vitrine works, including a series of skewered hearts that, unlike the original 2005 Kiss of Death, involve not real flesh but simulacra. A room designed to create spin paintings stood idle, with buckets of paint lined up ready on a metal walkway above a giant centrifuge.

Many of the workers are artists, but there are also technicians who know how to deploy formaldehyde, for example. At one table six people added spots to the spot paintings that in recent years have featured the tiniest spots visible to the naked eye.

Hirst visits the studio, sometimes several days in a row, at other times sporadically, to check on progress. A former pill miner remembers Hirst as an avuncular presence at one of Science Ltd’s legendary staff parties – before he went to the toilet and returned to launch an unprovoked verbal attack that was all the more startling for his previous friendliness. These days he is a more reliable boss. One Dudbridge employee said Hirst has an attention to fine detail that can be demanding – and that his involvement in the work is intense – but he is courteous. Staff turnover is low, and many people have been with him for years. There have been two serious attempts to shrink the roster, sparked partly by worries over cash flow but also, said Jude Tyrrell, a director at Science Ltd, because of Hirst’s yen for long-lost simplicity. “We’ve definitely had a few moments where it’s just been so stressful that you just think, ‘God, can we go back to what it was?’ It’s that sense of losing the freedom, being increasingly corporate.” She paused: “The beast, the machine, I think we all feel a little bit encased by that.”

Hirst did make a half-hearted break for freedom once. In 2008, he declared he would be stopping the butterflies and spins. This was just before he bypassed his galleries and put up 223 new pieces of his work for sale at auction at Sotheby’s in Old Bond Street. The two-day event earned him headlines – and £111m. Hirst claimed he wanted to democratise the sale of art, but the stronger impulses behind the sale, titled Beautiful Inside My Head Forever, seem to have been his desire to spark a new sensation and wrest greater independence. The auction secured the former, but even its hefty payoff couldn’t buy his liberty. As the gavel fell, Lehman Brothers was collapsing, and though the global crisis took a while to reach the wealthiest, collectors eventually became more cautious in a market awash with Hirsts. Prices for his work, according to a 2013 ArtTactic report, fell back to 2005/2006 levels.

So he geared up, not down, building Dudbridge and keeping the popular lines coming, often as personalised commissions: birthday greetings spelled out in butterflies, portraits of the wealthy expensively overlaid in centrifugal splatter. Science Ltd told the authors of the ArtTactic report that the number of Hirsts in existence at that point stood at 6,000 paintings and sculptures, and 2,000 drawings. Hirst is compiling a list of everything he has ever done.

At one end of the Dudbridge building, in a galleried, double-height hangar, some of his oldest vitrine works were back for inclusion in this catalogue or for repairs, under the sightless gaze of The Virgin Mother, his 10-metre-high statue of a pregnant woman, skin partially peeled back to reveal her internal organs in the style of an anatomical teaching model on superhuman scale. The upper gallery was a holding area for his newest work, still under wraps: a trove of sculptures in marble and bronze, many of them apparently mottled with corals and barnacles, jewellery and artefacts, and photo-realist paintings marking a departure from Hirst’s blunter confrontations with mortality and money.

Early reactions to this work have been mixed. Jay Jopling, his long-term gallerist, suggested showing the work in small batches, sparking Hirst to think big instead. The details of the coup de théâtre Hirst envisages for 2017, like the pieces themselves, remain shrouded.

Critics tore into the last exhibition of Hirst’s new work at the White Cube gallery in London in 2012 – which featured paintings made by Hirst’s own hand that relied heavily on ideas from painters he admires. He has always borrowed freely – or, some would say, filched. Hirst fields such allegations rather than ducking them. “I remember seeing Picasso’s bull’s head made from a bike handlebars and seat, and thinking, ‘Fuck, that is brilliant, amazing to be that original,’” he said. “And I thought that’s what you’ve got to do when you’re an artist: you’ve got to come up with something like that. And then, when I got to Goldsmiths, I realised that you don’t need to do that. I remember just thinking: ‘Steal everything.’ Because it’s all been done already.” He insisted this does not produce copies, but works of their specific time. “The only advantage you’ve got is being in the now, today. Once you say, ‘Don’t try and be original, just try and make art,’ then you go, ‘Fucking hell, I can make great art,’ because you’ve suddenly got the freedom – the same that advertisers have got to take from anywhere to communicate an idea.”

British advertising blossomed in the decade ahead of the YBAs, and at the centre of both phenomena was Charles Saatchi. His 1983 campaign for Silk Cut cigarettes, which impressed Hirst, was inspired by the Italian conceptual artist Lucio Fontana, who slashed his canvases. “I think the public in England is incredibly visually educated because of the complexity of advertising in the last 30 years,” Hirst told an interviewer in 2004. “People are visually educated through being sold things. So they understand everything.”

Hirst’s family residence is surprisingly like other homes of the wealthy in a cosseted stretch of suburban south-west London: pocket-sized gym, small indoor pool and a breakfast bar overlooking a neat lawn. He lives here with his sons, Connor, 20, Cassius, 15, and Cyrus, 9; their mother remains at the house the couple shared in Devon until their 2012 split. A rumpled sleeping bag in Hirst’s front hall adds to the impression of domesticity, but it is a bronze by Gavin Turk.

Hirst pronounced that it was time to spin, leading the way to an open-plan kitchen and dining room, and a table piled with colour, a feast of inks, marker pens and crayons. A free-standing cube revealed itself as a machine for creating spin drawings – smaller, less messy siblings to spin paintings. Hirst fixed a piece of paper to a circular board housed inside the cube to contain spatter, then depressed a foot pedal to spin the board while adding pigments.

Watching a spin drawing in progress is like talking to its creator: simultaneously dizzying and hypnotic. Anecdotes encircled fragments of anecdotes. Jokes bled into discussions of mortality. A debate on the merits of the Rolling Stones versus the Beatles (Hirst is a Beatles man) elicited vivid vignettes. “They had this weird fucking Ukrainian morris dancer,” he said, recalling a bash hosted by Ukrainian oligarch and art collector Victor Pinchuk, “and they got me, Jay [Jopling] and Paul McCartney up doing this fucking dance.” The image was left hanging as Hirst jumped to another encounter with McCartney, this time at an event hosted by Jopling, when McCartney performed magic tricks for Hirst’s sons.

A different kind of sleight of hand drew Hirst to the Beatles, he said: their redemptive ability to reinvent themselves. “All my favourite artists from the past, the way they move forwards is what interests me … And the way they stop being one thing, like the Beatles – the way they totally reinvented themselves and changed into something else.” He riffled through a monograph on John Bellany, pointing out how the artist’s brushwork and composition deteriorated as his alcoholism intensified, then admired a late-era work. “Look at that. Pissed as a fart, pissed out of his mind. But it works. You can see he’s taken months painting it. He’s having to lose it and get it back. And that’s exciting.”

Control, and its loss, remains an obsession for Hirst. Though praising the rewards of sobriety (“everything is better; even shagging”), Hirst spoke fondly of his former life and retains a soft spot for hellraisers, not least John Hoyland. Hoyland drank a lot and made big art, painting on as large a scale as US abstract expressionists such as Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman at a time when London galleries couldn’t accommodate canvases of that size. In other respects Hoyland appeared a kind of anti-Hirst, a purist about his work and hopeless with money. He once turned down a commission to make a painting for Coca-Cola’s London headquarters, Hoyland’s son Jeremy said, despite being “flat broke … For very understandable reasons Coke felt there were certain things that should be part of the work. And he couldn’t do it, so he didn’t.”

Now Hirst is seeking to reassert Hoyland’s position. He started by befriending his one-time opponent. Jeremy Hoyland remembers a phone call from his father after the artists’ first meeting: “I think I might have underestimated [Hirst].” During the last years of Hoyland’s life, Hirst supported the older man, setting up a standing order to buy his paintings. The arrangement continued after Hoyland’s death, and is only now coming to an end, providing a funding stream that has helped Hoyland’s widow, Beverley Heath-Hoyland, to manage the estate. Hirst owns more than enough Hoylands to stage Newport Street’s opening show.

Hoyland’s paintings are undoubtedly beautiful and, according to Hirst, “cheap for what they are”. The exhibition is likely to boost interest in the artist, in turn raising the value of Hirst’s collection. But this was not a prime factor in the decision to give Hoyland the first slot at Newport Street, Hirst said. “I like the idea of pointing out in the art world things that have not been seen or noticed. Another reason is that if there are any problems with the space, I didn’t want any big, complicated sculptures. For the first six months, it’s great to have a painting show, really simple. And then if you have air-conditioning problems, or a leaky roof … ”

Newport Street itself is likely to appreciate sharply as the gallery transforms the area. Local planning and development bodies saw Hirst’s arrival in Lambeth as cause for rejoicing, but as affluent visitors begin streaming into the area and hipster coffee shops displace businesses eking a living under the railway arches opposite the gallery, there has been grumbling. Yet Hirst’s aspiration appears not so much to deploy art as a tool of gentrification, as to open his gallery – and his collection – as widely as possible. “He was always insistent that you must have free entry,” said Collishaw. “He wants people to have the experience he did, when he had absolutely nothing but could walk into a gallery and have this totally transformative experience.”

Hirst is rediscovering the powers of a curator – to draw outsiders into his vision, to recreate the moment he first stood, rapt, in front of that blue Hoyland in Leeds. He has run up against the limits of the control he can exercise over his own realities, but is relishing the prospect of determining other people’s. This may, in the end, prove his greatest talent.

Newport Street Gallery opens to the public on 8 October 2015 with John Hoyland: Power Stations (Paintings 1964-1982). For updates follow @NPSGallery, newportstreetgallery.com

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion