For centuries mankind has built mighty monuments dedicated to their endeavours, and while today we may lean towards huge infrastructure projects as opposed to war memorials, the exuberance, and on occasions ridicule, they engender can still excite the public imagination.

Over the years, many grand schemes have been hatched that would have transformed the face of London. Engineers and architects planned to solve society’s ailments and built a new urban utopia.

Though we might shudder at what was planned by men with ideas as lofty as their finances were shaky, they were often motivated both by personal gain and a real vision for a better society.

From schemes to improve transport to grand monuments memorialising mighty deeds, these are some of the unbuilt plans that could have changed how we look at London today.

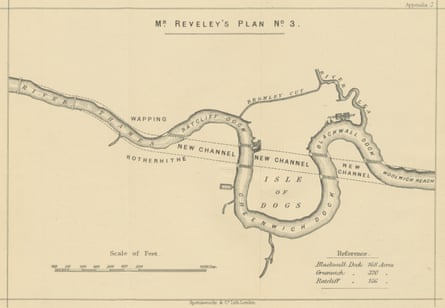

Straightening the River Thames

The opening credits to EastEnders would look rather different had a scheme designed more than two centuries ago by Willey Reveley been carried out: to straighten out the River Thames.

The idea had some merit as merchants could save valuable time cutting out the huge loop of the Isle of Dogs to deliver goods to the port of London.

The discarded loops of the river would have become massive sealed-off docks, creating in just a few years enough warehouse space that would take the dock builders decades to achieve.

The scheme eventually failed and London retained its distinctive curvy Thames, thanks to the machinations of the City authorities who were worried about a loss of trade at their warehouses.

Flying into the Isle of Dogs

In the 1980s, the planners of the Docklands’ redevelopment set out a new airport to whisk city folk around Europe – but just 40 years earlier an airport with six runways had been planned.

At a time when planes were small, and the runways were also considerably smaller, six runways would have sat comfortably at the top of the Isle of Dogs .

The plan was as much about improving air traffic for those who could afford it, as improving cargo services to the centre of the city.

The plans – which were drawn up by Riba – were never taken that seriously. Planes were growing fast and within a few years this brand new airport would have been hopelessly incapable of coping with the sorts of aircraft landing at Heathrow.

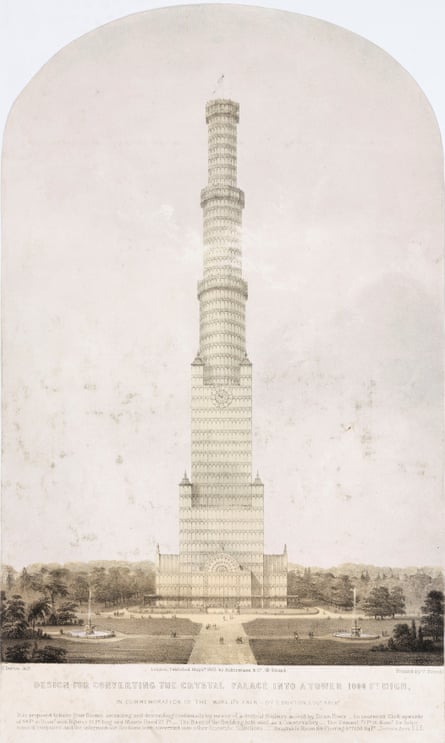

The Victorian skyscraper

When the massive Great Exhibition of 1851 was dismantled, a number of plans for what to do with the temporary prefab structure included what would still be London’s highest skyscraper.

Proposed by Charles Burton, the skyscraper would have stood at around 1,000 ft high, and thanks to its elevated location in Sydenham, south London, the summit would be 100 ft higher than the Shard, currently London’s tallest building.

“Vertical railways” would have carried people to the summit for the views, while curiously, a giant clock would have been the centrepiece half way up.

However, the investors favoured keeping their feet on the ground, and instead built the Crystal Palace.

Had the skyscraper been attempted, it is likely that the weight of the ironwork would have brought the whole thing crashing down – though a fire would eventually destroy the Crystal Palace.

A cable car for North Greenwich

It may surprise some to learn that ex-London mayor Boris Johnson’s cable car across the Thames was not the first attempt at cable car in North Greenwich.

Back in the days of cool Britannia when expectations that the exhibition at the Millennium Dome would rival the Great Exhibition in popularity, doubts started to emerge about what to do with the visitors.

The Jubilee line looked like it might be late, so plans were announced for a cable car linking the Dome with the north side of the river: the Meridian Skyway.

It got as far as securing planning permission and raising most of the money needed to be built, until the Dome exhibition organisers were accused of scaring off investors with gloomy predictions about passenger traffic.

With visitor numbers to the Dome far lower than hoped, dreams of flying across the Thames were to remain just that until Boris came along with his own cable car, sponsored by an airline.

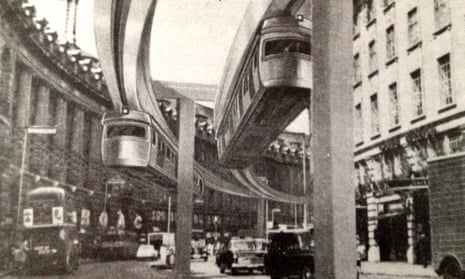

Central London monorail

Nearly 50 years ago, plans were published to scrap many of London’s famous red buses to replace them with something that could have become just as famous – a monorail network.

The scheme was proposed by Brian Waters, and endorsed by Desmond Plummer, leader of the Conservative opposition at the GLC. It would have seen four large loops built above the streets of London carrying the monorail services.

The plan was not entirely unmerited as bus usage was in decline while cars were clogging up the streets. Replacing the buses with a monorail was seen as a way of increasing space for the motorist without adversely affecting public transport users.

How close we came to a fleet of monorails zipping around above Londoners’ heads is unclear, as despite early political support, the plans vanished within a couple of years.

High Paddington

Imagine a new urban village with a lofty church atop a series of tall residential towers, all built over a major railway line into London – that was High Paddington.

It would have seen three massive tower blocks built on a concrete plinth raised over the railway lines on the approach to Paddington station.

Designed in 1952 by the architect Sergei Kadleigh (of Barbican fame), the towers would have housed around 8,000 people, with their own school and a dedicated church for this new urban town.

The intention was to house tenants who would have been displaced by tearing down the remains of London’s slum housing. It was the archetypal council estate, a decade ahead of its time.

However, it was never built, more due to lack of support from the media. Today the area is a cluster of other high-rise towers in the form of luxury homes and offices.

The democratic tower

While most monuments have traditionally been built to commemorate great people or great conflicts, a massive tower was once planned to celebrate democracy.

A tower designed by Richard Trevithick in 1832 to commemorate the Great Reform Act was a column almost as tall as the Shard, made from cast iron and covered in gold. And, perched 1,000 ft above the streets of London would have been an equestrian statue.

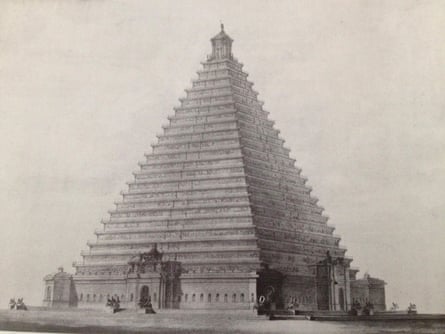

Trafalgar Square pyramid

Central London would have looked a lot different had a 200-year-old plan been carried out. In 1815, the land that is now Trafalgar Square was occupied by stables and the King’s Mews. And the MP Sir Frederick William Trench felt it was the perfect site for a monument in the shape of a massive stone pyramid.

It would commemorate the the Battle of the Nile, which coincidentally was won by Nelson, who is more famous for the Battle of Trafalgar and now stands atop the square’s column.

Trench felt that the Nile was a more important battle to remember, and planned a very Egyptian monument in the heart of London.

Taller than St Paul’s Cathedral, and double the size of Trafalgar Square, this massive Egyptian interloper would have dominated the skyline for miles around.

Fortunately Trench’s plans gained very little support, and a few years later the land was cleared – much to the relief of London’s pigeons.

Britannia Triumphant

Just to make sure the world knew of Britain’s naval power, in 1799 plans were announced to create a 230 ft high statue in Greenwich that would have dominated the landscape for miles.

Fortunately, the plans were widely ridiculed in the press, and the designer himself withdrew them – although only to lend support to a rival scheme to commemorate British naval victories in Egypt.

New York has the Statue of Liberty, and London nearly had Britannia Triumphant.

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter and Facebook and join the discussion

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion