‘I still have my life force’

Ivan Roitt, 87, is emeritus professor at Middlesex University’s Centre for Investigative and Diagnostic Oncology. He lives in Finchley, north London, with his wife, Margaret. They have three daughters and six grandchildren.

There was no conscious decision – I just went on working. When I finished as head of immunology at University College London, after 25 years, a colleague asked if I would like to go to Middlesex University. I thought, “Let’s do something useful”, so I set up the cancer research centre.

You can’t switch on wanting to do things like that. You’ve just got to be damned lucky that there is inside you this little engine, the mojo, the life force, prana, whatever they say in yoga. And knowing it is there, you might as well use it.

Doing research is exciting. The trouble is, you need money, and I spend a lot of time trying to squeeze it out of people. Part of my job is to get everything out of my university colleagues – I think of them like my children – in terms of tackling new research. And those attempts to inspire them act as intellectual stimuli to me. During the day, I don’t feel tired at all.

So I don’t want to give it up. I’m not waiting around on the incinerator. I don’t want to rot. Not as long as I have my life force. When you get to my age, you can’t help but think that there is something not too far away, that you are going to come to a stop, and I mean a real stop. It doesn’t depress me. I think if you approach it with humour, it can make it slightly easier. I’ve told everybody that at my funeral I want a song called Incinerator Flues, based on St James Infirmary Blues.

Margaret, my wife, prefers it if I keep to the two days a week that I go to the university and don’t bring too much work home. She wants us to be together – we’ve been married for 61 years.

I’m extremely interested in politics, read the newspaper, listen to the news, write to my MP. I’m an opera lover, I like eating, I love novels – I like to feel my life is being enriched. I have done a mindfulness course and I think that helps. I’d like my epitaph to read: “Here lies a guy who was always trying right to the end. He was decent with a capital D.”

‘I’ve been at every night out they’ve had’

Jean Miller, 92, is cloakroom attendant at the Vidal Sassoon hair salon on Princes Square, Glasgow. She drives the 25 miles from her home in Falkirk. She is a widow and has a son and two grandsons.

When I first came here, I thought, “What on Earth am I doing in among this young crowd?” But I’ve been here 17 years now and I love it. They are quite a cheeky lot sometimes. There was a rule made: “Don’t swear in front of Jean.” Half the time now, I don’t hear what they’re saying, but when they say, “Oh, sorry Jean”, I know.

My husband Johnny was the district manager for a household supplier, and I was a sales representative there for 29 years. I retired at 60, in 1993. But I couldn’t stand it. I now work three days a week, from 9am to 4.30pm, and I get my hair done all the time. I am included on all the nights out. They are absolutely hectic. It starts off nice and calm, and before the end of the night everybody is swinging about. I’ve been at every night out they’ve had since I started.

Lots of people say I am youthful. I don’t know about that, but I have looked after myself. I take cod liver oil tablets every morning. I had bowel cancer 10 years ago and the surgeon said to me I had five years. I said to him: “Five years! I am expecting to live longer than that.”

If you’ve got an interest in people, that’s what gets you out to work. I know I will need to stop some time, but it will be when I really have to. There’s no way I am sitting in a chair.

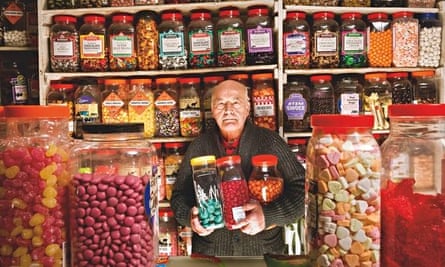

‘The shop keeps my memory going’

Tom Swan is 79 and runs Swan’s Sweet Shop in Renton, West Dunbartonshire. He has worked there for 60 years, and lives just a few minutes away with his wife, Mary.

My granny bought the shop in 1945. She also had a chip shop and a drapery. The shop is open from 11am until two, when I go home for my lunch, then I come back at three until 8.30pm.

I came here when I was 18; my two aunties worked here as well. It was a busy, busy place. Everything was loose then – peas, barley, sugar: they all came in hundredweight bags. I made them up into half-pound bags, which were tuppence ha’penny in old money.

The shop is open from 11 until two, when I go home for my lunch, then I come back at three until 8.30pm. I still sell bread, fizzy drinks and a few staples, but I had to change the business when the grocery trade was going down. Supermarkets killed groceries. Now I sell sweets: Edinburgh rock, sherbet lemons, jelly beans, pineapple rock, midget gems.

People come from far and wide – it’s like a pilgrimage to a wee sweetie mecca. A lot of older people’s carers come in to get their sweets for them. It is helpful for their memories: they taste a Coulter’s candy or a cinnamon ball, and it takes them right back. They don’t remember their husbands, but they remember the sweets. I’ll just stick working here. It keeps my memory going, and hopefully I’ll not have to sit in a home with someone feeding me boiled sweets.

I enjoy the weans that come in and the excitement on their faces when they see the hundreds of different types of sweeties. Though they look at a boiled sweet as if it’s poison – they’re used to getting crisps, Milky Ways, Mars bars, stuff that’s easy eating.

I am going to keep going until I die. What else would I do? I don’t fish and I don’t golf. And anyway, I’d miss the sound of the sweeties hitting that scale, then the soft noise as they land in the paper bag. That’s the soundtrack of my life.

‘I couldn’t live on my pension’

Sidney Htut, 70, is a psychiatrist with Kent & Medway NHS Trust. He lives in London with his Burmese wife, Nita. He has a son, a daughter and three grandchildren.

I lost my job as a research scientist in my 50s and I was discouraged from continuing because people said I was too old. Then I came across someone who became a psychiatrist at the age of 60 and that gave me inspiration. The training was very challenging, but I knew I could do it.

I applied for training jobs but didn’t get them – they gave all sorts of reasons, but the main reason was my age. I eventually got a senior house officer job in Wolverhampton. After a year, I applied to the Kent & Medway NHS Trust and I got the job. But it involved driving long distances, so I moved and I am very happy: the atmosphere, colleagues, patients. I’ve got job satisfaction and it makes me smile.

Working as a psychiatrist suits me since it is less demanding physically, but does involve mental strain – I am quite tolerant of that. I love working with people who have learning disabilities. Nearly all of my clients have difficulty expressing themselves and are reacting to something going wrong. My duty is to determine what that is – is it their mental health or their environment, their carers or are they in pain? I relish the challenge of finding out what is wrong and trying to help them. I still do this work, because it gives me deep satisfaction.

But I also work because I need money. I lost my job, sold my house, then bought this flat in 2005, so I still have a mortgage. My first wife died of cancer and Nita and I got married just three years ago. If I retire, I won’t be able to support her, because my service in the NHS is less than 10 years and I wouldn’t get a substantive pension and be able to live on it. I came to the UK from Burma in 1989, and Nita left Burma to live with me – we lived on the same street when we were children. If we didn’t have money, it wouldn’t be fair on her, because she comes from a very rich family. As long as my health permits, I am thinking of working for roughly another five years, but I might just keep going. I do a lot of meditation and that is very helpful for my health and my work. I’ve just taken up the guitar again – I’ve not played it since I was at school. Nita and I, we’re very happy together – we like our life like this.

‘My customers know they have to behave’

Evdokia “Ducia” Stafford, 90, has run the Beehive Inn in Pencader, Carmarthenshire for 60 years. She is originally from the Donbass region in Ukraine, and her British husband, John, died 14 years ago. She lives alone at the pub, has no staff and opens every evening.

I was tired of moving around and told my husband I wanted my own place, so he bought me this. When I came here, it was just two little cottages. I stripped it and opened it up. I like working: why would I stop? Where can I go? I’ve got a nice place here, so I might as well stay.

When I came here, at first people would come from all over to see me, because there were no foreign people in Wales. There had maybe been Italian prisoners of war, but no one from Russia – they had never heard of it, I think.

I didn’t speak English (my husband and I talked in German), but slowly I started to learn. I was going to learn Welsh, but I couldn’t do it all – Russian, German, English; Welsh was too much. I can read English, but I can’t write it. I just do my business by telephone and pay by cheque, and my neighbour helps me with letters if I need it.

I open at 5pm and close when the last go. Most people who come are middle-aged, so they go home early. With young people, there’s no conversations, they’re just on their telephones, texting. They’re not banned, but when they come here they have to behave. I’m quite strict. I have thrown people out before. In some pubs there’s mess in the toilet and writing all over the wall, but nothing in mine. People know.

It’s quieter now, because you can’t smoke inside. It’s mostly local people from the village who walk up. It’s good enough for me. I open every night, but they don’t come every day because they can’t afford it any more. I serve them, have a game of dominoes with them or whatever. They go home and I lock up. It keeps me going, it pays its way and I don’t need much at my age. I just like a little company.

My husband wanted me to pack up. He was not a well man in the end and he was sorry that I did all the work and he couldn’t help me very much. I told him: if you’re happy in the house and I’m happy working here, that’s fine.

I’m not going to retire. I enjoy working. During the second world war, I was made to do farm work by the Germans following their occupation of Russia. I had to work so hard, but I think they made a good person out of me. I didn’t have the chance to go out and socialise, but that’s OK. Now everybody knows and respects me.

‘To suddenly do nothing would be a disaster’

Brian Denney, 82, is a pensions consultant. He lives in Harewood, near Leeds, with his wife Jill. They have two daughters and four grandchildren. In his spare time, Brian is a deputy honorary colonel in the Territorial Army, and a deputy lieutenant of West Yorkshire.

In 1958, I and a colleague started an insurance brokerage – I was 24. That prospered and expanded. My colleague retired in the late 1990s and I just carried on. In March 2010, I sold the firm and the new owners asked me to stay on, and offered me a three-year contract. I enjoyed what I was doing. To suddenly do nothing would be a disaster, both mentally and physically. The contract was due to expire in March 2013. Before it expired, the owner said he’d like me to stay on longer, if I’d like to. He said, “You tell us when you’ve had enough, and we’ll tell you when we’ve had enough.” I said, “That sounds a very good arrangement to me.”

I go to the office, I go and see clients, and do at least three days a week. I see lots of people who are coming up for retirement. Most of them, when they come in for the first or second review, are still the same person. But then they start to deteriorate. I am talking about executives. And those that haven’t got any hobbies deteriorate very quickly. Because the mind and the body do deteriorate if they’re not used.

A lot of people I speak to are members of a pension scheme and their sole object in life is to get to 65, because they are not happy doing what they are doing. That is extremely unfortunate. The most important thing is to enjoy life. If you don’t enjoy what you are doing, stop.

Jill, my wife, would be worried if I was doing too much, but I think she is pleased that I have an interest outside the home. I think it must be quite boring for people who are together all the time, no matter how much they love each other. It doesn’t stimulate conversation.

I would stop if I didn’t have the ability to do my job properly. I hope I would realise before anyone else had to tell me. One thing I had to pack up this year was skiing. As you get older, you don’t mend as quickly, and I have to acknowledge that.

‘I feel more tired when I’m not working’

Pat Thomson, 73, is a freelance offshore materials and logistics superintendent, working on North Sea oil rigs and platforms around the world. She lives in Matlock, Derbyshire, and has three children, nine grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

There’s a lot of fun in the work I do. Although it is hazardous, it is exciting because you have all sorts of different environments to deal with. I would hate to be in a monotonous desk job. The lads on the rig are very respectful, because I am so much older and also because I never ask for anything special, though they can be pretty cheeky to me. In the early days, it was a challenge. It definitely wasn’t a female environment then.

I work and sleep – there’s not a lot else you can do on a drilling rig. But you have a family atmosphere, because you are living together 24 hours a day, for 21 days at a time. If you didn’t get on with people, it would be a nightmare.

I work very long hours, often 16 hours a day. I can get called out at night when I am sleeping. It’s stressful and tiring, but there’s something challenging about it. I often look at those people turning a stop/go sign on the side of a road and think, “Oh my God”. I know they can go to their own beds at night, but there mustn’t be much job satisfaction. Sometimes there can be a situation where we are having a breakdown and the whole rig can shut down, and I have to go and suddenly charter helicopters, get all the equipment flown out. That is quite satisfying.

I left school with no qualifications. When the children were young, I started going to night school and got higher English and maths. Then I got accepted for primary teaching, did that, and then went to BP. I found it male-oriented, so I did something to make me different and did a higher national in business studies through distance learning. Then I decided I was bored again and did the Open University in foundation maths, pure maths, applied maths, physics and engineering. So I’ve got a BSc in maths and engineering.

I feel more tired when I am not working – I tend to sit around and go to bed early – but when I’m offshore, I am in the office by six o’clock in the morning and I’m not in bed till nine or 10 at night. I thrive on that – I don’t know why. My grandchildren say I am mad, but I’m not one for housework or knitting: I like working.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion