Trudging through the remains of The Witcher 3's earliest villages, protagonist Geralt comes across a priest. That’s not an uncommon sight, as the Church of the Eternal Fire holds a great deal of sway over the townsfolk looking for some greater meaning in lives ravaged by war. This holy man, however, has a job for Geralt: to scorch the nearby smoldering battlefields further, so as to dissuade carrion-eating monsters from making his charges' lives that much worse.

It's a bleak solution to a fantastical problem and one that fits our hero's profession of “professional monster slayer” perfectly. But it quickly branches off into a very different story, as Geralt finds a survivor among the "corpses." That survivor contradicts the priest's story about how he got there, and sends Geralt off to confront his would-be deceiver.

The sidequests in The Witcher 3 can vary greatly in length and long-term importance; some are relatively self-contained, others have consequences that don't reveal themselves for hours. What these missions all have in common, though, is a story that's worth witnessing in its own right. It’s part of what sets the game apart from your typical open-world game, which simply features the same dozen or so objectives Jackson Pollock'd hundreds of times across maps. While impressively rendered, those worlds don't warrant much exploration on its own.

For a prime example of this problem, look at last year's Assassin's Creed: Unity. The game sported a map waterlogged with chests to loot, sigils to collect, and the occasional bystander to assassinate. Unity was so packed with stuff that publisher/developer Ubisoft bailed out some of the seepage into companion apps, mobile games, and its omnipresent Uplay service.

But looting "Animus Fragments" and treasure chests doesn't tell us anything more about the Paris chapter of the Assassin Brotherhood or about the game’s protagonist. Instead, these missions are narrative dead ends: boxes to check on a list that fuels that easy, shallow shot of dopamine for "finishing" something.

When the explosive cost of AAA development means a game that sells 3.4 million copies can be a failure, companies are tripping over themselves to force bigger, more detailed, and increasingly expensive environments into their games. But the things players are asked to do in those worlds don’t always seem to justify these massive worlds.

Deeply detailed vanity

The Witcher 3 has its share of repeated content, but even that can work to the game's favor. As a witcher, Geralt is half exterminator, half detective, studying the monsters he's contracted to slay to more cleanly combat them. It's natural for him to prod surrounding bandit camps and monster nests. More often than not, those diversions lead to something new, regardless. It's padding, but it serves a purpose, and those engaged enough with the story the game wants to tell can happily spend the 200 hours or so needed to see it all.

The best open-world games feature side content that goes beyond engaging players' inborn desire for completion. Take Grand Theft Auto V, which sports some of the best core missions in the series in the form of heists. These heists have little to do with the open-world that contains them. The content between and to the sides of those missions—the parts that take place in the "open world"—aren't as repetitive as Unity's collect-athon, but neither are they as compelling as The Witcher 3's interweaving stories.

Instead, they're just... dull. This filler content serves only to remind the player that, yes, you can walk, drive, and bike from one end of the fictional city of Los Santos to the other. Tailing or towing targets or driving from point A to B to watch a cutscene provides an excuse to motor around an obsessively detailed Los Angeles stand-in. It also raises the question of whether Rockstar's goal was to make a game that's fun to play or a vanity project that's fun to look at.

It's not just because spectacle sells, though just the phrase "open world" seems to come with a set of expectations for size and structure. It's gotten to the point where Nintendo is using the term in conjunction with the next The Legend of Zelda title, a series which has always allowed players to go pretty much wherever they want.

Our shared vision of what an open-world game should be, and the expectations that come along with that vision, make these games perfect receptacles for the kind of post-release DLC that has become almost expected in recent years. Ubisoft and Warner Bros. exploit that addictive demand for more content better than most, with plenty of towers to climb, thugs to interrogate, and terminals to hack.

Players clear away one dead-end objective to reveal more of the map, featuring several dozen new blind alleys to sidle into. For some, clearing that repetitive clutter is an addiction, while others are satisfied with unlocking the extra markers. The latter group is guaranteed to know just how big this year's model is compared to last's, even if they give up on the repetitive grind long before they ever experience it all.

Bigger isn't always worse

None of this is to say that bigger is inherently worse. The debate over game length versus value rages on, and both sides have merit. Games are expensive—not just as an industry, but as a hobby—and for some people that padding makes a $60 new release into a better value proposition.

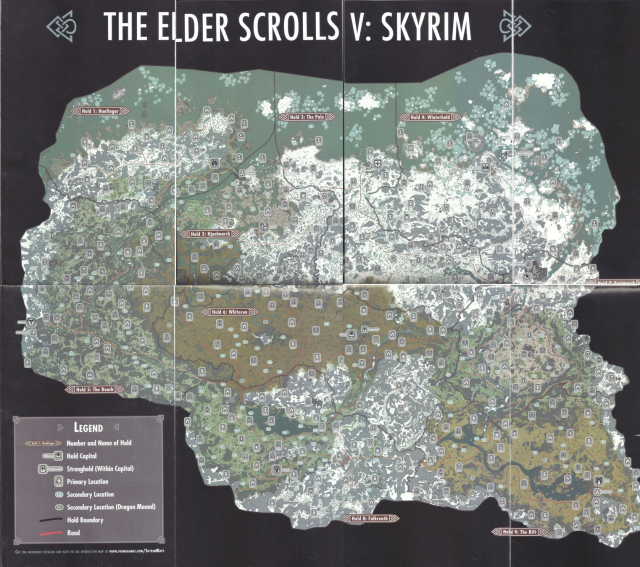

The Witcher 3 certainly isn't the first massive game to avoid the filler problem, either. The Elder Scrolls and Fallout follow a very similar philosophy toward optional missions. Dusting off a mage's journal about a failed spell or stumbling onto the remains of some strangely evolved Vault society fills the world with enriching detail. The Persona franchise, on the other hand, unfolds a deep and meaningful world full of character and charm through 80-plus hours spent on a path so linear that there's actually a calendar to tell you how many in-game days have been mapped out for you ahead of time. Persona 4 succeeds not in spite of this linearity, but because its laser focus makes every moment of the story meaningful.

Those games that can't justify spreading outward perhaps ought to look forward in much the same way. Stripping down the size of Los Santos, with its plodding car towing and crate loading, might have allowed for more time to be spent crafting more and better heists, resulting in a longer, finer string of GTAV's best content. A smaller world would limit some of the cop-ducking bombast of previous games in the series, but there are already some alternatives which specialize in exactly that. The same goes for Unity's assassinations, which haven’t been a core focus of the Assassin’s Creed series for years.

With so much money, time, and talent being put to work on games of this size, players shouldn't have to choose between content that's engaging and content that just fills up space. Games like The Witcher 3 prove that we can have both, and we shouldn’t settle for less.

reader comments

140