A friend of mine has just witnessed the silent death of a little girl in one of Gaza's frantic emergency rooms. She had no parents beside her, no name to humanise her. She spoke no word and made no plea. Her eyes focused steadily on the ceiling, oblivious to the desperate and heroic efforts around her. And then she was gone – another anonymous body hidden under a white sheet.

Who was she and why did she die? The Gaza story currently circulating on Twitter and Facebook gives two opposing answers. The first labels her a human shield for Hamas, a pawn in their terrorist machinations to undermine Israel's security, kill its citizens and destroy its international standing. The second calls her a martyr to Israel's genocide against the Palestinian people, a victim of Zionism's deliberate disregard for Palestinian lives and the world's long-standing political immunity to Palestinian suffering.

These viewpoints are as impenetrable as the Iron Domes air defence system. Since the deadly and heart-rending blitz against Gaza began, most Israelis, Palestinians and the watching world have taken shelter under one or the other, blasting away any counter-message that threatens their viewpoint. These have nothing to do with this girl, with the reality of her life, her hopes, her sorrows. Nor do they reflect any of the social or political transformations that would have kept her safe.

I know this gladiatorial narrative only too well, because I've heard it every day of my childhood. My mother is a daughter of Zion. One side of her family fled from Russian pogroms in the Pale of Settlement (the region of Imperial Russia in which permanent residency by Jews was allowed until 1917), the other was caught up in the rise of Nazism in the cauldron of 20th-century Europe. Her adopted sister was one of the last children to be saved on the Kindertransport. My grandmother used to recall the tiny girl without a word of English who wept for her mother, father and baby brother every day for months; later she would visit their ashes at Auschwitz.

Ingrained in her psyche, and that of millions like her, is the belief that Israel exists to dam a global tide of anti-Jewish rage – that any breach of its security would let the floodwaters in, sweeping her family away once more. A woman who sings her grandchild to sleep every summer night, who despises the settlers and Judaic zealots alike, hardens when Hamas rockets slam into Ashkelon. I watch her transform into someone who could countenance any kind of strike back. "We have to protect ourselves," she told me after watching the BBC news last week, nearly in tears. "We do it now, because we did not do it then. Hamas knows it. And yet they still stand next to their children and send the rockets to kill ours."

My father's family belongs in the other camp. He was only a boy when the Irgun and Haganah came rolling into Jaffa on a wave of tanks and mortars. His wealthy Palestinian family clung onto their home and orange groves through the terrifying war, only to lose it in the bitter years that followed to Israel's layers of regulations and property codes. They scattered across Europe and the Middle East – much like the Jews – searching for ground to build on, mourning an irreparable loss. They are also haunted by a kind of survivor guilt. They know that as much as they've suffered and lost, they've still escaped the camps of Lebanon, the brutality of life in the West Bank, the pain of seeing land and livelihoods swallowed year by year by settlements, the rubber bullets and the real ones.

On July 19, my Palestinian cousins, children of my father's younger brother, marched on the Israeli embassy in London. They carried placards and horrifying pictures – of bodies on the ground missing limbs, of children whose brains could clearly be seen through fractured skulls, of weeping parents and weary doctors. They were supported by tens of thousands of others, many of whom know only the emotive basics about the tangled history of this conflict. Their rage is motivated by a simpler, appositely Biblical storyline – the fury of watching a bloodied David struggle against an apparently ruthless Goliath – stronger, richer, arrogantly powerful, who still attacks sleeping children with F16s.

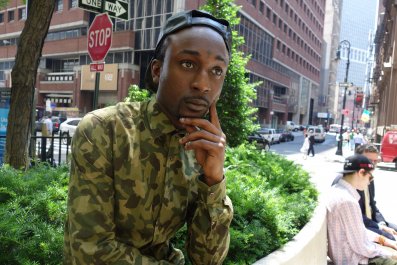

I find myself standing between bunkers, exposed to fire from both sides. I recently launched a novel, inspired by my parents and their brave attempt to rewrite tribal hatred. As the book hit the shelves, the bombs began to rain on Gaza. And as the blitz transformed into a ground offensive, every social media site began to run the kind of vitriolic, hate-filled attacks that dogged my childhood and eventually tore my parent's marriage apart after 25 years of raising us in hope.

There are atrocities taking place in Gaza, without equivocation. The nameless little girl and 100 other children did not have to die – not for Israel's security, not for the Palestinian plight. Their death was a deliberate choice, or rather a succession of choices driven by cold political considerations.

Israel's prime minister Binyamin Netanhayu's brutal attack on families with nowhere to hide will not weaken Hamas in the long run. And Hamas can never bring Israel to its knees or shame its allies with rockets. More than 500 Palestinians and at least 18 Israelis have been sacrificed on the altar of this deluded strategy. When we eventually emerge from the chaos, no one will be safer. And many of the wounds created can possibly never heal.

This conflict defies rational argument and bypasses understanding. Here are people so blinded by pain that they cannot recognise suffering in anyone else. Jews and Palestinians have spent so many years beating each other and being beaten that they have become nothing more than a bruise and a stick. Victimhood has become a national religion. The right to "self-defence" is a holy creed for both sides. And the impossible search for justice, the redemption of all the wrongs of history, has become a blind alley to salvation.

Arabs and Jews are not condemned to be enemies. Growing up, I saw so many more similarities than differences between my two tribes, sharing stories of loss, of scattered families and fresh starts. I have a daughter now who carries both bloodlines and must somehow learn to live at peace with the two sides of her heritage. I have seen her in every picture of a Palestinian child bloodied on a hospital gurney, or every Facebook post from an Israeli parent running from an air raid siren. I see her in that little girl who died without a name, representing nothing more or less than tragic missed opportunities. I can only pray for the other Palestinian and Israeli children watching bombs and curses fly around their homes today. Perhaps they may still have the chance to fulfil those opportunities together.

Claire Hajaj is the author of a novel inspired by her parents, Ishmael's Oranges.