Back in 2004 as I stood in the hot summer sun of the Syrian desert, a German archaeologist told me something that I thought, at first, I had misunderstood. He was explaining that the Palmyrenes had imported dates from Egypt. Turning and surveying the vast expanse of date-palm groves that wrapped around the Temple of Bel to the east I asked the inevitable question: “Why?” The answer was one I had heard before. “Because they could.”

Two years before, I had briefly worked in Abu Dhabi to fund my research in Syria – six weeks of work there covered a year’s expenses in the Syrian desert – and I had heard this answer when I had asked why Dubai Zoo had bred a “cama” (half camel, half llama). It suddenly came to me why Palmyra was so exceptional. It was the Dubai of its day. Anything was possible for those with money and a whim for the exotic.

The very remoteness of the site has meant that Palmyra has always been shrouded in mystery and romance. In the 1870s Isabel Burton, the wife of the rakish British explorer Sir Richard Francis Burton, wrote of the need to engage a troop of Ottoman soldiers to escort them across the desert to Palmyra. So prevalent were attacks by marauding hordes of bedu that only the most determined and well-armed parties made it to admire the fabled ruins of this ancient oasis and trading city.

The writer Gertrude Bell, an archaeologist among many other things, reported similar problems in the first decade of the 20th century and it was only in the latter part of the century and, after a hiatus in the aftermath of 9/11, in the years running up to the current civil war, that Palmyra began to be visited by tourists in any significant number.

This geographical isolation meant that, in addition to its romantic location, Palmyra also remained exceptionally well preserved. Almost two millennia after its most distinctive buildings were constructed, visitors could easily imagine themselves walking the streets of a living city.

The presence of water on the site means that there were people in and around the oasis for thousands of years, with archaeological evidence reaching back to the Neolithic period. A small settlement in the vicinity of the Eqfa springs had expanded into a substantial city by the Hellenistic period and it was at this time that the Palmyrenes were already importing dates from Egypt; but this was not yet the height of the city’s affluence.

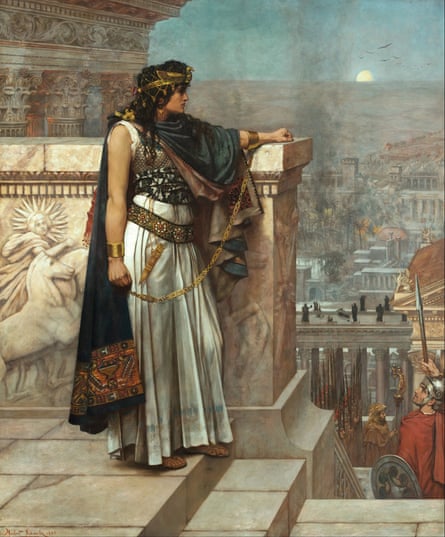

Palmyra attained the zenith of its wealth and influence in the second and third centuries. Rome ruled with a light hand that allowed the local population to maintain their language, fashions and gods. Anyone who encounters a funerary relief of a Palmyrene woman is struck by the glamour and opulence of these well-heeled matrons. Although all wear similar boxy veils, there the similarities end; each is adorned with a variety of personalised broaches, rings, necklaces and jewelled diadems.

The overall impression of bling and ostentatious display is comparable to the lives of the Kardashian family today. Among the wealthy, conspicuous consumption was the order of the day but the poor were naturally as present in Palmyra as in any other city and it was they who kept daily society functioning.

Palmyra was dominated by the temple of its most influential god, Bel or Baal, in a vast enclosure beyond the east end of the main street, the Roman decumanus that ran on an approximately east-west axis across the city. The reliefs now standing beside the entrance to the central cella give a vivid illustration of the ritual life of the temple as nimbed figures with spiky rays emanating from their heads offer pomegranates and other objects on altars while an eagle swoops above.

The gods of Palmyra are depicted as superhuman figures beside the same altars on which their devotees would make their own sacrifices. The source of the wealth of the city is acknowledged in the reliefs of camel trains, where the camels carry shrouded canopies that could be transporting the silks and spices that fed the trading economy in a long trail that led all the way to distant China. Behind them walk a party of enigmatic shrouded women: mourners, religious devotees or simply veiled travellers? Their identity remains opaque.

Another panel displayed in Palmyra museum shows that this land-locked settlement did not lack knowledge of the wider world and indeed its commercial interests spread far and wide, as this relief shows an intricately rigged ship sailing a turbulent sea.

The vibrancy of its art is what most people who have seen Palmyra take away with them; from the figures in the Temple of Bel to the funerary reliefs of the middle and upper echelons of local society or simply the sinuous grapevine motifs that wind across the lintels of numerous doors, these are the details that bring the city to life. Walking the main colonnaded thoroughfare, it is possible to see pavements scratched with tables for board games to amuse traders on a day of slow trade and columns etched with announcements in both Greek and Palmyrene script.

The most romantic view of the city was not, as many thought, to view the rising sun from the castle but to sit with a cold drink at sunset on the terrace of the Zenobia Hotel. It was built in the 1920s and was a haunt of Agatha Christie and her husband Max Mallowan.

After a long day in the ruins, a visitor could sit there and imagine both the glories of the Roman city and the gilded society of the interwar years. Dominating the view was the perfectly preserved cella of the Temple of Baalshamin, Lord of the Heavens, and second only to Bel in the hierarchy of Palmyrene gods. Missing only its cult statue and its ceiling and home to an artfully twisted tree, this temple captivated generations of visitors to the site.

Having visited countless times between my first visit to Syria in 1997 and my final trip before the war in 2010, this is perhaps the scene that comes most readily to mind when I close my eyes and imagine Palmyra. I remember two or three days in particular. I was hosting a group of Little Sisters of Jesus in Palmyra with camel rides (side-saddle naturally), visits to the Temple of Bel and a picnic in the castle. I then smuggled them into the Zenobia to use the WC – no easy task when you have six nuns to disguise as tourists – before checking in and relaxing with a visiting friend by sitting and watching the Temple turn slowly red-orange in the evening light.

Most poignantly of all, I recall a Saturday afternoon when my friend Jacques and I ran away for a few hours to sit on the Zenobia terrace drinking cold beer and simply enjoying the view, which was never the same on two different occasions.

I have had reason to think often on that afternoon over the last few months. Jacques, or Fr Yaqub Mourad, to give him his full name, was abducted from the town of al-Qaryatayn in May. Last week the monastery where he lived, and where I lived and worked alongside him for three years, was destroyed by Islamic State. Two days later I heard about the Temple of Baalshamin; all that remains are memories.

Emma Loosley is an associate professor at the University of Exeter

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion