We interrupt our regularly scheduled weekly home media new release column for a special bulletin: today, three of Pam Grier’s most iconic 1970s vehicles make their Blu-ray debut, which is indeed a cause for celebration. But revisiting these low-budget treats as a group serves as a sharp reminder that Grier wasn’t just a sexy mama in campy exploitation movies (though she was, and they were); she was a singular talent and a force of nature, the likes of which we haven’t seen since. As such, she remains an icon, an untouchable, lionized and idolized by equal proportions (and multiple generations) of brothers, sisters, hustlers, and movie nerds. What was it that made Pam Grier so special — and has made her endure for so long?

In the exploitation-film equivalent of that old chestnut about how they found Lana Turner at the soda fountain of Schwab’s, Grier was reportedly discovered at American International Pictures not as an actress, but as a receptionist. Jack Hill, maker of scrappy low-budget programmers, thought she had something and cast her in his 1971 women-in-prison picture The Big Doll House. It was a decidedly supporting role, but audiences couldn’t take their eyes off Grier, and Hill quickly moved her into the leading role of the 1972 pseudo-sequel, The Big Bird Cage. And it was Hill who created what would become her defining role the following year.

She’s slyly introduced in Coffy well within the less-than-favorable terms typical of women in “blaxpoitation” pictures, first defined (while still off-screen) as a “piece of tail,” appearing in low-cut come-hither duds and purring wowzy come-ons like, “Do I look like the kinda woman one man’d be enough for?” to a crime boss, nude by the six-minute mark. And then, as the opening sequence comes to a conclusion, Hill and Grier pull the turn: she takes out a sawed-off shotgun, barks a fierce “This is the end of your rotten life, you motherfuckin’ drug pusher” at her would-be paramour, and blows his head clean off.

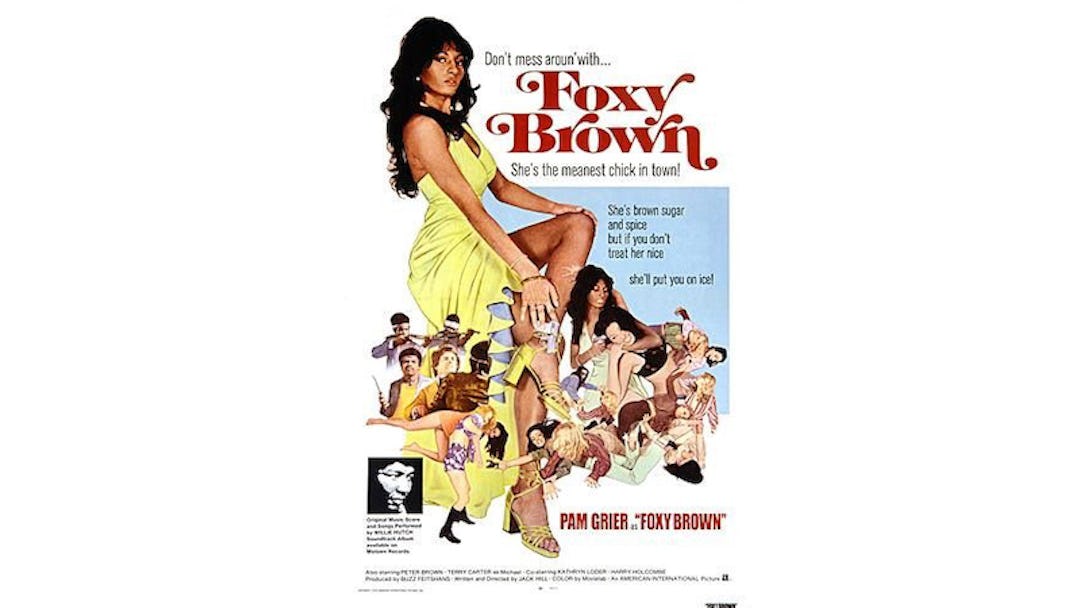

There’s a similarly great moment at the end of Hill’s Coffy follow-up, 1973’s Foxy Brown, when she takes out a room full of baddies who think they’ve frisked her by pulling a tiny pistol from her big, beautiful Afro. Both are great reveals, but they also show how the filmmaker and his muse were brilliantly subverting the expectations of the exploitation film. “The typical woman’s role in a black exploitation movie, up to now, has involved maybe one bedroom scene right at the beginning, where she’s making love with her man and his telephone rings,” Roger Ebert wrote in his original (mediocre) review of Coffy. “The girl then essentially has nothing to do until the end of the movie, when she gets to welcome the hero back to bed. If she is lucky enough to have a scene in the middle, it’s probably designed to feed male chauvinist egos.”

There is little of that in these films. To be sure, pretty much every man in them regards Grier’s characters purely as sexual beings — but she knows the score and will take advantage of it whenever possible, whether she’s honey-potting her way to the top of the drug trade in Coffy or going undercover as a hooker to get to a “pink-ass corrupt honky judge” in Foxy Brown. She also takes the opportunity to insult his manhood via a ruthless critique of his sexual organ; both films culminate in a literal emasculation of a male villain, via a shotgun blast between the legs during the climax of Coffy and the slicing off of a member by her henchmen at the end of Foxy Brown (“He’s ready, sister,” they tell her, followed by a zoom in on the poor sap’s face, and a cut to a sage nod from our Ms. Grier). The scuzzy men she encounters may see her only as a sexual bullseye, but Pam Grier always gets the last laugh.

This wasn’t accidental; Hill was one of the exploitation filmmakers who often snuck in his own sociopolitical subtext between (and sometimes during) the shoot-outs and cat-fights. Both Coffy and Foxy — and to be clear, they’re basically the same movie, the latter initially intended as a Coffy sequel before AIP inexplicably balked (yes, Virginia, there was a time when studios didn’t want sequels) — find Grier’s character penetrating the underworld as revenge for family members hurt or killed by the ravages of drugs. Their anti-drug stance made them unique in the world of Super Fly; so did their social justice inclinations, made more explicit in Foxy Brown, which pauses for a discussion of the limited opportunities available to Foxy’s brother (Antonio Fargas) and for a lengthy scene where Foxy meets with a Panthers-esque “neighborhood group” and pleads for “justice for all of them… whose lives are bought and sold.” Blaxpoitation movies were often classified, and dismissed, as easy escapism, but Hill’s Grier vehicles reminded their audience that they were surrounded by “the new slavery” of “hard dope,” creating a vivid reality for his heroine to triumph over.

The actors who play her antagonists and even her supporters are often shrill and unconvincing, which makes Grier’s talent all the more apparent. She delivers Hill’s (sometimes clunky) dialogue with ease and charm, and is about as believable as you can be in situations this ridiculous. You never get a sense that she thinks she’s better than the material, even though she is; in all of these movies, she’s playing it seriously without taking it seriously, which is a subtle methodology that even the most respected “serious actors” often can’t pull off when they’re slumming it in popcorn pictures. “She seems to be having fun,” Ebert wrote of her in 1975, “and the characters she plays seem more athletic, more active, than a lot of the action roles played by aging male superstars.”

All of that said, it’s easy to overstate the feminism and political thoughtfulness of these movies, which are often buried too heavily under oogy exploitation elements and uncomfortable miscalculations; both Coffy and Foxy have a scene late in the film where the racism of her tormentors veers into an explicitly master/slave relationship, which is way too heavy for these lightweight B-movies to bear. But even in those scenes, Grier can’t be muted — you know they’ll get theirs in the end.

If anything, the defining characteristic of her early exploitation movies is the charge they’re given by her mere presence — by the electricity of a substantial black female action hero (a minority within a minority in the genre, then and now) blasting and slicing and kicking her way through 90 minutes of cheerful carnage. The movies were cheap, but she was a million-dollar commodity. By Foxy, the dancing-silhouette opening credit sequence (aped years later by Superbad), with its focus on her winking eye and ample bust, accompanied by Willie Hutch’s tribute song, amounted to a sequence where the sound and image was all about celebrating Pam Grier. It was, and it remains, pure iconography.

By 1975’s Friday Foster (the third film in the new-to-Blu trio), however, Grier was looking to expand her persona beyond oft-nude ass-kicker. Producer/director Arthur Marks based the film on an early-‘70s comic strip, meaning this movie made it official: Pam Grier was a comic book hero. But it’s also a film of higher production value, with a terrific supporting cast (Yaphet Kotto, Carl Weathers, Eartha Kitt, Godfrey Cambridge, Scatman Crothers, Ted Lange, and Paul Benjamin all turn up) and a lighter, more comic tone. Her Friday is a fast-talking girl reporter (OK, photographer, but still) in the Howard Hawks/His Girl Friday mold, calling her editor “boss” and sneering at Cambridge’s suggestion that she “go home” and “have a baby or something.”

But she also only picks up a gun a couple of times, which is both an understandable stretch and a letdown; it’s a little disappointing to see her become a cowering nonentity during the climactic shoot-out, knowing how Coffy or Foxy would’ve been right out front. In a way, it foreshadows the softening of her persona in the years that followed, as it became clear that more mainstream interests didn’t have the foggiest notion of what to do with a talent like Pam Grier, and ended up plugging her in to a series of forgettable character turns. (Her biggest ‘80s role was in the Paul Newman vehicle Fort Apache the Bronx, where she played, wouldn’t you know it, a junkie prostitute.)

But her cultural currency would increase big time in the 1990s, when the increased home-video popularity of her blaxpoitation classics put her back on the film-nerd radar, particularly after Quentin Tarantino rewrote the lead character of Elmore Leonard’s Rum Punch for Grier, redubbing her (and the film adaptation) Jackie Brown. (He also lifted two cues from the Coffy score for his movie.) His Grier heroine was older, wiser, and more easygoing, but she could also wield a gun and growl a threat with the best of them. Some of the impact of those original films lay in the novelty of seeing an African-American woman of her strength and gravity at the center of a motion picture. Sadly, it was still a novelty in 1997, and even worse, it remains one today. Maybe one day it won’t be so unusual, and we’ll be able to just enjoy films like these as period relics, with goofy hair and giggly costumes. But until that day comes, they retain much of their vitality, and energy, and power.

Coffy, Foxy Brown, and Friday Foster are all out today on Blu-ray from Olive Films.