Even in the fledgling Soviet Union there was no escape from the influence of Hollywood. When Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks visited Moscow in July 1926, they were mobbed by fans whose love for the US’s hottest celebrity couple was oblivious to the ideological divide between the nations. Newsreel footage of their visit was incorporated into a comic film, A Kiss from Mary Pickford (1927), which ends with the transcendent moment when America’s sweetheart nuzzled up for a photo op with Russian actor Igor Ilyinsky.

Artists were as likely to be struck with what the Soviet director and theorist Lev Kuleshov sniffily called Amerikanshchina (or Americanitis) as the fans. The era’s leading film-makers engaged productively with the style of US films, which gave rise to the distinctive montage technique of Soviet cinema in which editing is used to create dramatic tension.

Owen Hatherley’s intriguing new book goes beyond these matters of technique, and explores how Soviet cinema, and its wider culture, absorbed two American imports: the industrial theories of Henry Ford and Frederick Taylor, and the slapstick comedy of Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton. The Chaplin Machine traces an enjoyably idiosyncratic path back and forth between film studios and factories on opposing continents. This book was partly developed out of Hatherley’s postgraduate research, and so is more academic and less pithy and personal in tone than his previous publications on modernist architecture, austerity nostalgia and Pulp. Nonetheless, its wide embrace of cinema, architecture, politics, design and engineering offers intellectual excitement as well as rigour.

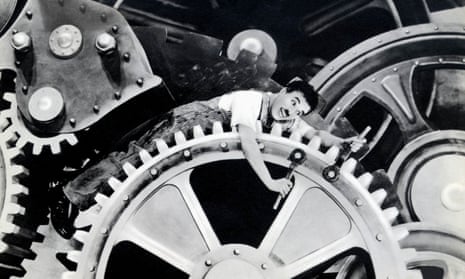

If you have seen Chaplin battered, outpaced and mangled by giant machines in his 1936 film Modern Times you will be able to visualise the essence of Hatherley’s argument, how art can express the absurd comedy and inhumanity of the mechanised world. “This book,” he sets out in his introduction, “is about people who imagined turning industrial labour into a circus act.” Chaplin’s horror of automation gives colour to his argument, and the “machine men with machine minds and machine hearts” speech from The Great Dictator (1940) opens the book. Counterintuitively, the minute, perfect movements of Chaplin’s performances in his early shorts gave him, for such Soviet theorists as Viktor Shklovsky, the appearance of an automaton or marionette. Likewise, the spectacle of workers repeating small, mindless movements on an assembly line merges the man into the blankness of a machine. Manual labour and screen performance are rendered inhuman, which makes them both frightening and funny, and echoes the formalist principles of estrangement that fed into constructivist architecture.

Accordingly Chaplin was the “ideal actor” for the authors of the Eccentric Manifesto, published in 1922 in Petrograd, who cherished popular artforms above the highbrow: the circus, the music hall and the riotous slapstick comedy churned out by the Keystone studio. Kuleshov’s feature-length film Extraordinary Adventures of Mr West in the Land of the Bolsheviks (1924) combines the tropes of Hollywood slapstick with the rush of Soviet montage and parodies of German expressionism. All this, in the name of lampooning its guileless American heroes (a Harold Lloyd lookalike and a cowboy), and their misapprehensions about Russia. In this relentlessly fast‑paced and bizarre comedy, the American Mr West is terrified that he will fall foul of bloodthirsty Bolsheviks on a business trip to Moscow. Instead he is captured by a group of thieves who play on his fears until the real Bolsheviks come to his rescue and demonstrate the achievements of modern Russia. Hatherley pinpoints the “gleeful” pleasures of this anarchic film, with underworld characters played by a cast of odd-looking “anti-stars”.

The other titan of American slapstick, Buster Keaton, channelled his knowledge of engineering into a strain of mechanical comedy, visible from his first two-reelers to his masterpiece The General (1926). In One Week (1920), when a love-rival switches the numbers on the component parts of Keaton’s DIY prefab, the result is an absurdly contorted family home with doors and plumbing in all the wrong places, at mystifying angles, and rotating from its base. Hatherley finds the influence of One Week’s tipsy machine-home in Soviet architecture. First, he identifies the film as a parody of a Ford promotion, mixing “architecture, technology, motorisation and slapstick”. Then he follows the efforts of architects to respond to this combination, and the “fast, unsentimental, high-tech” films from the US in general. He kicks off with Weimar architect Erich Mendelsohn, whose sleek design for the Universum cinema in Berlin followed his dictum that there should be “no rococo palace for Buster Keaton”.

Hatherley’s analysis of Soviet film posters by Nikolai Prusakov and the Stenberg brothers is revelatory and especially shrewd. The posters’ disjointed montage-style designs are a graphical representation of the mechanisation of the city, and of the human body – but skewed in a westerly direction with the addition of primary colours, endless skyscrapers, flapper fashion and Ford motor cars.

Chaplin, and Chaplinism, would eventually fall out of favour in the USSR, with Eisenstein condemning the “method of infantilism” in Modern Times. As Hatherley’s book reaches the sound era, it returns to the assembly line, which stretches from films made in support of the Five Year Plan as hymns to national efficiency, to the birth of the Soviet musical in the mid‑30s. Hatherley describes the Hollywoodesque revue film Jolly Fellows (1934), for example, as a work that out-eccentrics the eccentrists, with its perfectly synchronised dancing girls showing a debt both to Busby Berkeley and Ford. But the taste of Amerikanshchina had become bitter. The animated figures of Chaplin, Keaton and Lloyd appear in the film’s opening sequence, only to be followed by the sardonic caption: “These are not the stars of this film.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion