How a Broken Economic System Keeps Roma Children in Special Schools

By Miroslav Klempar

In the late 1950s, in what was then Communist Czechoslovakia, the government decided that Roma were different from the rest of society, and should therefore be educated separately. These racist assumptions led to today’s two-tiered school system, in which mainstream schools offer quality education to a majority of non-Roma, while Roma children are overrepresented in special schools.

To be sure, no child belongs in a special school of any kind, in the Czech Republic or anywhere else. Every child has the right to quality inclusive education, and when all children are educated together, regardless of their differences, everyone benefits.

The language used to describe special schools has changed over time—about a decade ago, they were renamed “practical schools” so the government could claim it had abolished special education. But school segregation endures, and the mechanisms that enable it are rather complex. Let me tell you about how it works in my own city, Ostrava, the third-largest city in the Czech Republic.

At the age of six, on enrollment day, children take a series of tests in school. At a mainstream, high-quality school, for instance, children might be handed a drawing of a dog, an elephant, a house, and a forest. The questions will ask them things like, “Which animal belongs in the house, and which belongs in the forest? Isn’t the elephant too big for the house? Have you seen an elephant before?”

A month after the tests are administered, Roma parents typically receive a letter saying that their daughter is “too shy,” that their son is “hyperactive,” or that either one of their children is “intellectually inferior” and would be better off in a special school. Sometimes the message is even simpler: “Your child is not accepted.”

There’s an economic aspect to this systemic discrimination that goes beyond simple prejudice. Special schools receive 80 percent more state funding than mainstream schools. This gives teachers in special schools a financial interest in getting Roma and other children channeled into these institutions. A steady flow of students ensures these teachers can keep their jobs, which pay better than the average teaching position in an elementary school.

It’s because of this system that the Czech Republic has the highest proportion of special teachers in Europe, comprising a powerful political lobby. Meanwhile, in mainstream schools, teachers fear that enrolling Roma pupils will lead non-Roma parents to pull their children out of their schools, which could shrink classes and lead to staffing cuts.

But there is a way out. According to the School Act of 2004, enrollment tests are permissible, but they cannot be used to refuse a child enrollment in a particular school. Ultimately, it is up to parents to decide where their children will be enrolled. But most Roma parents are unaware of this and are intimidated by the teachers, so they follow their advice and send their children to special schools.

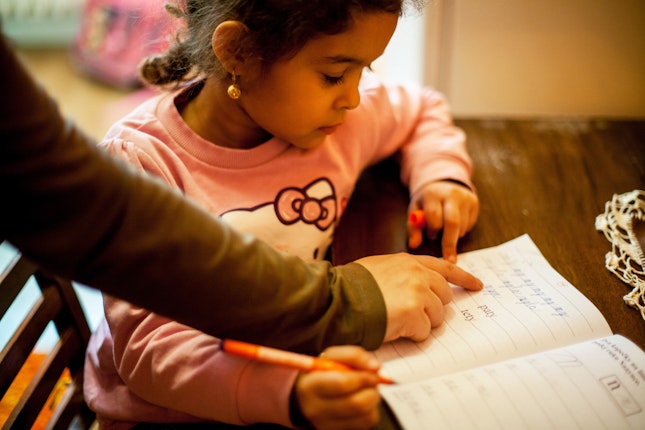

I joined two other Roma community organizers from Ostrava, Jolana Smarhovycova and Magdalena Karvayova, and together we decided to take a pragmatic approach to changing the status quo. Over the past three years, we have been going door to door to invite Roma parents who have children that are about to turn six to community events at which we explain what they should expect at enrollment days. We inform them about what the tests might look like, and stage a mock enrollment day. Then we remind them that, in the end, they are the ones who decide where their children will go to school. We encourage them to place their children in mainstream schools and to convince other parents to do so, too.

Over the past two years volunteering parents have led enrollment campaigns where they live, offering support to parents and children during the enrollment period, monitoring the enrollment process, and challenging discriminatory behavior from teachers during the tests. Together, we have set up an informal group of Roma parents fighting for equal education named Awen Amenca (Come With Us, in Romani).

This mobilization has paid off. In the past three years, around 200 Roma children were enrolled in mainstream schools—from 34 the first year to over a hundred this year. Moreover, six classes from segregated schools have not opened this September, having been closed down for lack of pupils. And this month, legislation abolishing school classification altogether will be implemented, though whether it will have any meaningful impact on the segregation of Roma children into special schools remains to be seen. Only by dismantling the special education system will the Czech government fulfill its obligation to provide quality inclusive education for all children in mainstream schools.

The government is engaging in blatant discrimination when those with a financial interest in perpetuating systemic segregation are compromising the futures of generations of Roma children.

Editor’s note (September 16, 2016): An earlier version of this post did not fully explain the Open Society Foundations’ position on inclusive education. We advocate for the right of all children to learn together. Learn more about the importance of inclusive education.

Miroslav Klempar is a fellow of the Open Society Roma Initiatives Office.