The Revision of Steve Jobs

The man who made computers personal was a genius and a jerk. A new documentary wonders whether his legacy can accommodate both realities.

An iPhone is a machine much like any other: motherboard, modem, microphone, microchip, battery, wire of gold and silver and copper twisting and snaking, the whole assembly arranged under a piece of glass whose surface—coated with an oxide of indium and tin to make it electrically conductive—sparks to life at the touch of a warm-blooded finger. But an iPhone, too, is much more than a machine. The neat ecosystem that hums under its heat-activated glass holds grocery lists and photos and games and jokes and news and books and music and secrets and the voices of loved ones and, quite possibly, every text you’ve ever exchanged with your best friend. Thought, memory, empathy, the stuff we sometimes shorthand as “the soul”: There it all is, zapping through metal whose curves and coils were designed to be held in a human hand.

No matter how many years have passed since 2007, and no matter how many generations of iPhone have come and gone, there is still something, in the machine’s anthropological alchemy, a little bit magical. And a little bit mystical. Which is probably why one of the most long-standing clichés about iPhones, and the iPods and the Macs that preceded them, is that they were the first pieces of technology to inspire not just loyalty, but love—love!—among their users. It is probably also why the man who helped to will those products into existence has already been included in history’s pantheon of world-changers and paradigm-shifters. Gutenberg, Lovelace, Darwin, Einstein, Edison … and Steve Jobs. People who, as Jobs liked to say, “put a dent in the universe.”

And there is very little argument to be had here: That’s exactly what Jobs did.

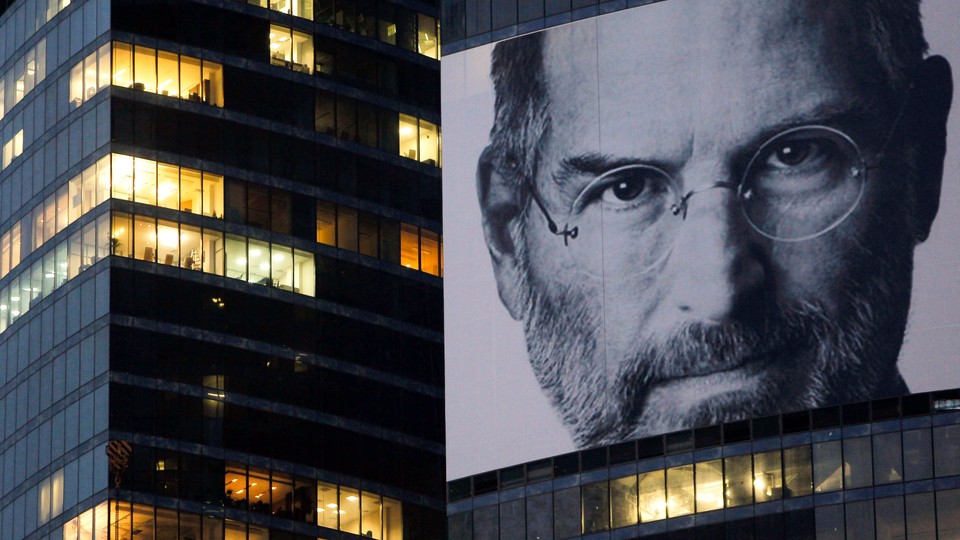

But how, exactly, did he do it? The method in the magic is the subject of Alex Gibney’s new documentary Steve Jobs: The Man in the Machine—think Going Clear, but about a person—which offers a decidedly unsympathetic treatment of the man who insisted that “computer” should be spelled with an “i.” The film isn’t arguing against Jobs’s membership in history’s elite cadre of Dent-Putters; it is arguing, though, that he—and we—deserve more than the empty conveniences of hagiography. It’s attempting to rethink Jobs’s legacy in a way that implicates the legend and complicates the lore. The film opens with images of the makeshift memorials erected in Jobs’s honor after his death in 2011. “It’s not often,” Gibney (the film’s narrator as well as its director) remarks, “that the whole planet seems to mourn a loss.”

Cut to a clip of a YouTubed tribute to Jobs starring a kid who looks to be about 10 years old. “He made the iPhone,” the young eulogist says. “He made the iPad. He made the iPod Touch. He made everything.”

It’s quite fair to say, with due respect to both the networked nature of invention and the severe limitations of the great man theory of history, that the kid is right: The iPhone, and the many other devices Apple has produced over the years, exist because of Steve Jobs. He may have been more of a “tweaker,” as Malcolm Gladwell put it, than an inventor, but he was the vision guy. And he was the sell-the-vision guy. Gibney acknowledges that. “He had the ability,” Regis McKenna, who designed Apple’s earliest and most ground-breaking marketing campaigns, tells the director in an interview, “to talk about what this computer could be … He gives people this feeling of forward movement.”

Jobs’s vision—informed by Buddhism and Bauhaus and calligraphy and poetry and humanism, a willful fusion of ars and techne—led to the machines into which so many of us pour our souls and our selves. He staffed Apple with people who “under different circumstances would be painters and poets,” but who in the digital age would choose computers as the medium through which “to express oneself to one’s fellow species.” He emphasized artistry, and spirituality. As Gibney’s voice-over points out: An iPhone’s screen, when the power has gone off and the light from beneath it has been extinguished, ends up reflecting its user.

All of which makes it tempting to ignore another thing about Steve Jobs: He could be, on top of so much else, a terrible person. Not just a jerk, occasionally and innocuously, but a bully and a tyrant. (“Bold. Brilliant. Brutal,” The Man in the Machine’s tagline sums it up.) Jobs regularly parked his unlicensed Mercedes in handicapped spots. He abandoned the mother of his unborn child, acknowledging his daughter only after a court case proved his paternity. He betrayed colleagues who stopped being useful to him. He made the still-useful ones cry. This is on top of the apparent disdain for charitable giving and the Gizmodo fiasco and the stock fraud suit and the many horrors of Foxconn.

Those things—and the many other ones that live under the broad category of Steve Jobs’s Personal Failings—are well-documented, in blog posts written both before and after his death, in in-depth biographies both authorized and not, and in Jobs, the feature film released in 2013. Some of those takes treat his shortcomings as mere inconveniences, justifying them away as the common costs of uncommon genius. Others insistently minimize them, seeming convinced that the flaws will tarnish the sheen of their beloved universe-denter.

Others, though, do something that is arguably much worse: They suggest that Jobs’s failings as a person, rather than impeding his legend, actually bolster it. His uncompromising vision, his unapologetic bullying, his tendency to prioritize the needs of computers over the needs of people—all of that, the thinking goes, was somehow necessary. Jobs’s assholery, like his mock turtlenecks and his New Balance running shoes, made him who he was, and thus helped to make Apple what it was. Jobs could be a jerk in the normative sense because he could be a jerk in the narrative. His successes justified his failings.

The Man in the Machine rejects those easy tautologies. Here Jobs’s flaws are not just a footnote, but a focus. Gibney interviews Jobs’s confederates and his critics and his betrayees, including former bosses (the Atari founder Nolan Bushnell), former friends (the early Apple engineer Daniel Kottke), former girlfriends (Chrisann Brennan, the mother of his daughter), former employees (the engineer Bob Belleville), and current critics (Sherry Turkle, the prominent skeptic of tech utopianism). We get analysis after analysis of Jobs the Jerk, some of them frank (Turkle: “He was not a nice guy”), others accommodating (Bushnell: “He had one speed: full on”), others resigned (McKenna: “I think that Steve was very driven and would very often take shortcuts to achieve those goals”), others indignant (Belleville: “Steve ruled by a kind of chaos: He’s seducing you, he’s ignoring you, and he’s vilifying you”), others angry (Brennan: “He didn’t know what real connection was, so he made up another form of connection”).

Each summation, each person, is a reminder of the sacrifices Jobs imposed on his co-humans in the name of human connection. As Gibney puts it: “How much of an asshole do you have to be, to be successful?”

The most intriguing interviewee, though, and perhaps the most damning, is Jobs himself. Gibney obtained previously unseen footage of the deposition Jobs gave to the SEC in 2008 concerning Apple’s options-backdating scandal—and the footage, spliced between scenes, functions as a kind of refrain throughout the film. In it, Jobs, clearly annoyed at having to submit to such questioning, occasionally cooperates with the SEC lawyer, but mostly fidgets and sulks and glares. At one point, he tucks his jeans-clad legs up onto his chair, reconfiguring his body into an upright fetal position. At another, when asked why he would want Apple’s board to offer him backdated stock options, he replies, “It wasn’t so much about the money. Everybody likes to be recognized by his peers.” He adds, “I felt that the board wasn’t really doing the same with me.”

There is, in this SEC interview of the CEO of the one of the world’s most powerful companies, a distinctly pouting petulance. And that somehow puts everything else—the betrayals, the bullying, the blithely self-centric worldview—into human perspective. Jobs was, maybe, a Great Man who was also, in many ways, a small child: self-absorbed and desperate to please, those two things not contradicting but instead, in ways productive and not, informing each other.

Does any of that matter, in the end? Was Einstein, too, something of a man-child? Would Edison, when questioned and challenged, have similarly tantrummed, tucking up his legs in a silent sulk? We don’t really know, mostly because these Great Men did their Great Things in the age before video, before social media, before blogs and depositions and the documentaries that convert their proceedings into media. They lived in a time that afforded people the luxury of being remembered, and defined, for the What of their lives rather than the Who. Steve Jobs did not have that luck. He lived in a time—we live in a time—when a new holism is being brought to bear on history, when our assessments of our heroes can take into account not just their achievements, but their personalities. When even legend-making can be a networked affair.

We live in an age of complicated idolatry. The irony is that we do so, in large part, because of Steve Jobs.

Megan Garber is a staff writer at The Atlantic.