It’s fair to say that Gala Fairydean Rovers, of the Ferrari Packaging Lowland League, is not one of the glamour clubs of British football. To its possibly bemused pride, however, the club has a grandstand, a miraculous work of concrete origami, which for force of constructional imagination and for architectural intelligence per cubic metre is hard to beat. While its levitating prisms anticipate by decades the work of Zaha Hadid, it has a taut to-the-point-ness that has never been bettered. As if to give a public demonstration of dimensions numbers 1 to 3, it is equally virtuosic in line, surface and mass.

Today it is clogged with alterations, so to appreciate its original purity it helps to look at the photographs taken in 1963, when it was new. One of these also shows the E-type Jaguar of its architect, Peter Womersley, though being black-and-white it doesn’t show that the car was gold. The Jag must have been a sight, amid the ancient rural beauty of the Scottish Borders, but then so were Womersley’s buildings. Rarely has there been a more unlikely setting for cutting-edge architecture than Melrose, Galashiels, Selkirk and other small towns thereabouts.

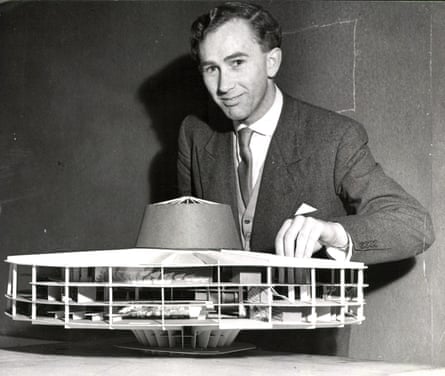

Womersley (1923-93) was, quite simply, one of the best British architects of the 20th century, and until recently one of the most overlooked. His buildings are adventurous but poised; lucid, brave in conception and considered in their detail. He knew how to be elegant in a classical modern way but also how to play with a mannerism – a strange window rhythm, an imbalance in the structure, a stretched proportion, an ambiguous material – so as to achieve a greater composure than if he had played only by the rules. Rebecca Wober, an Edinburgh-based architect who has done much to unearth his life and work, says he made “spaces that just sing”.

Although he was published widely in his lifetime, he doesn’t figure as prominently in official histories as others of equal or less talent. Only last summer – word evidently arriving too late to its Ayrshire location how fashionable and valuable mid-century modern has become – an exquisite house of his, perched like Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater over some coastal rocks, was destroyed. Historic Scotland had not thought it worth listing.

Now, thanks to the work of Wober and others, he has been getting more attention. Her partner, Gordon Duffy, also an architect, is currently striving to rescue a boiler house, designed by Womersley for a former mental hospital in Melrose, by carving five extraordinary multilevel apartments out of this crafted, sculpted, concrete building more noble than its function required. “If this were in Japan people would be paying huge amounts of money to come and worship here,” says Duffy of the contemplative space made by the industrial structure, although not everyone in the area sees it in the same way. “People always ask, ‘When are you going to demolish it?’” he says.

Womersley’s neglect is partly down to his personality. He was social and charming and he drove that car, very fast, around the country, but he was also elusive and private. He wrote no manifestos, joined no movements and played no networking games with his fellow professionals. He loved the sun, and made frequent escapes from the Scottish weather to Italy, Hong Kong and places in between – Jamaica, Cambodia, Iran, Hawaii. When he wasn’t globetrotting he worked from his small rural studio with only a phone line and the local post office to connect him to the outside world. He lived global and he worked local.

He trained, just after the war, in the Bauhaus-influenced Architectural Association in London, spent a short period as a labourer on the construction site of the Royal Festival Hall and briefly worked in Kuwait on the designs for a sheikh’s palace. Then came his first work, an accomplished and confident house for his brother near Huddersfield, called Farnley Hey. The designs faithfully followed the modernist principles of his education, but with sensuality in its camphor wood and York stone finishes and sociability in the flow of spaces through its multiply split-level plan. At its heart was a double-height space for his party-loving brother, a built-in audio system included, called the Dancefloor.

Word of the house spread. Huddersfield and its surroundings being a textiles area and the Borders being another, social threads connected them, through which Womersley came to work and live in the latter. He designed more houses, including one for the textile designer Bernat Klein, a light, spare frame for Klein’s life and work which while Californian in its optimism also belongs to the Scottish hill on which it stands. Some commercial and public projects came along – council offices, health buildings, a sports centre for the University of Hull, offices for some wool merchants and fellmongers.

Larger commissions sometimes brought conflicts. Womersley, says Wober, was “extraordinarily single-minded and he didn’t mind if other people flowed with it or not”, which could work better with like-minded individual clients like Klein than with public committees. An expansion of the Edinburgh College of Art, which as Womersley’s largest and most prestigious work would have secured him a firmer niche in history, foundered on grounds of cost. At the end of the 1970s, frustrated, and realising that his modernist approach had fallen from fashion, he moved to Hong Kong, a city in which he had already previously refurbished the Peninsula hotel and realised an office block with another architect, Walter Marmorek.

He then poured his thwarted creative energy into a design studio in the Borders for Bernat Klein’s business, a short walk from his house. It is a potent inverted ziggurat of a pavilion whose emphatic horizontals and more nervy vertical rhythms set the weight of concrete against the lightness of glass. From different angles it can seem ethereal or pugnacious. The concrete posts and beams evoke timber construction without losing the stoniness of the material. It generates a marvellous array of suggestions and ambiguities without overloading a small building, or swamping its fundamental pleasures of light, view and proportion.

Among the buildings that Womersley admired on his travels were the domed, tile-clad, ornamented mosques of Isfahan, for their combination of bold massive shapes and refined detail. His buildings look nothing like them, but they have the same properties. His designs could be called modernist or sometimes brutalist but mostly they are creations of his own personal universe. In this he has something in common with other Scottish-based individualists, such as Charles Rennie Mackintosh or the creators of St Peter’s Seminary, Cardross, Isi Metzstein and Andy MacMillan. As Womersley himself put it, in one of his rare public utterances: “My approach to architecture is relatively simple: I try and give delight.”

- A caption in this article was amended on 24 January 2017 to correct the location of Peter Wormersley’s Bernat Klein studio.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion