Some protesters simply stepped out from their front doors into the street. Most came from around London, while a few travelled across the country to be there. Last Sunday, more than 500 people joined hands around historic Norton Folgate neighbourhood in Tower Hamlets as a symbol of their wish to see the old buildings restored for reuse rather than being demolished. There were young and old, there were families and dogs, and among them was Stanley Rondeau, whose Huguenot ancestor came to the area in 1685.

Across the capital, Londoners are growing increasingly frustrated at the wave of large developments they feel are being foisted upon them. Most of the towers that are currently proposed for London have been devised to serve the international property investment market rather than provide genuinely affordable homes for Londoners, of which there is a chronic shortage.

The vast floor-plates of British Land’s development in Norton Folgate seem best suited to the corporate financial industries of the City of London, and are likely to be occupied by a single tenant. This is already the case with the neighbouring Spitalfields Fruit and Wool Exchange development, of which the entire office space has been leased to an international law firm. Significantly, this development was imposed upon Tower Hamlets by London mayor Boris Johnson, overruling the unanimous vote of the borough planning committee twice. The fear is that he will act in the same way with Norton Folgate.

The Spitalfields Fruit and Wool Exchange was formerly home to several hundred small businesses, for whom there is a shortage of office space in the capital. If the 19th-century warehouses of Norton Folgate are redeveloped and only their facades remain, affixed like postage stamps on the front of new buildings, the raised land value will ensure that the rental costs exclude all but large corporate tenants. Yet Tech City in Shoreditch evolved quite naturally in the post-industrial buildings that once housed furniture factories and other small-scale manufacturing. It would serve locally based businesses if the old warehouses in Norton Folgate could be restored in a similar fashion.

Thus this historic neighbourhood has emerged as a key battleground in the conflict over the future of London – as the potential for the city to become an arid forest of perfume-bottle shaped towers, serving the requirements of international capital, supplants the historical continuum of the lively metropolis, where rich and poor live cheek by jowl, where newcomers can build a life, and where small and large businesses thrive side by side. This is the sense in which the current battle is the one for the identity of London.

Sitting at the boundary of the City of London, Norton Folgate is a former medieval “liberty” created when the Priory of St Mary Spittal was dissolved at the time of the reformation. As an autonomous entity governed by its own residents, the Liberty of Norton Folgate was independent both of the rule of the City of London and of the church. And, even though the liberty was absorbed into the London Borough of Stepney in 1900, the spirit of independence is not forgotten – there are those who still claim that Norton Folgate’s autonomous political status was never formally abolished.

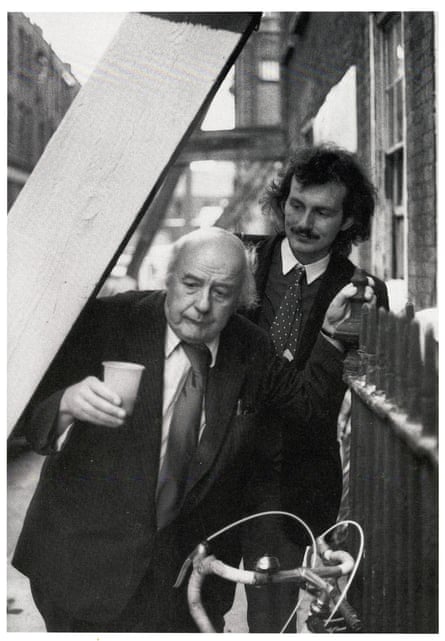

In a strange precursor of the current situation, British Land attempted to demolish part of Norton Folgate in 1977 but were halted by a group of young conservation activitists, including the art historian Dan Cruickshank, who squatted in the 18th-century weavers’ houses to stop the bulldozers. The Spitalfields Historic Buildings Trust was born and, with the help of Sir John Betjeman, it saved the neighbourhood, emerging as one of Britain’s most-respected conservation trusts through the following decades.

Now British Land faces the Spitalfields Trust in Norton Folgate again. The trust was essentially honed as a machine to stop British Land, and many of its current members took part in the first “battle”. Now they have 40 years of experience challenging developers behind them, and maintain close contacts with some of Britain’s foremost planning lawyers. Recently, the multibillionaire Troels Holch Povlsen stepped forward to support the Spitalfields Trust by providing significant funds as a war chest for any forthcoming legal battle. Thus the lines are drawn.

The trust’s defeat of British Land in Norton Folgate in 1977 was a seminal moment in British conservation history, when public opinion recognised the necessity to balance “progress” in the form of new development with the need to preserve national heritage. With the wellspring of popular feeling against development at this moment, it is possible that Norton Folgate may become the testing ground again in which commercial imperative is set against cultural significance. Additionally, whatever happens in Norton Folgate will affect other looming developments such as the nearby Bishopsgate Goodsyard, and in this sense it may also become the crossroads that defines the direction of future policy in urban development.

British Land seeks to demolish more than 72% of the fabric of its site in Norton Folgate, which lies entirely within a conservation area. If this were to go ahead, then any conservation area might be at risk of similar treatment and the term loses its meaning. As with the proposed Smithfield Market redevelopment and the Strand terrace that King’s College sought to demolish, English Heritage is supporting the developers in Norton Folgate, and finds itself on the wrong side of public opinion for the third high-profile case in London in a row. Yet English Heritage changed its opinions over the Strand, advocating the retention not demolition of the buildings when the secretary of state called a public inquiry.

In an open letter to the Spitalfields Trust, sent before Sunday’s protest, British Land’s development director Mike Wiseman said it was wrong to describe its plans as “corporate plazas for big corporate occupiers”, adding that it was “disappointing that you have chosen to misrepresent our plans, despite the time we have spent consulting and amending the design in line with many of your comments”.

But the 500 people who joined hands around Norton Folgate on Sunday wanted to express their love of London and its history, of its diverse life and infinite variety. And as more of the vast developments currently threatened in the capital are enacted, the passions of Londoners will continue to rise.

Today, Tower Hamlets’ strategic development committee meets to decide on the British Land proposal for Norton Folgate. Whatever the outcome, it is unlikely to be the end of this story.

POSTSCRIPT: On Tuesday 19 July, after a three-hour hearing, Tower Hamlets Strategic Development Committee voted unanimously to reject British Land’s development proposal for Norton Folgate, citing the low level of social housing and the inappropriate height and massing within a conservation area as their primary reasons. The council had received 576 letters of objection, and 12 in support of the proposal.

The Gentle Author writes daily about the culture of the East End at www.spitalfieldslife.com

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter and Facebook and join the discussion