The US military never gave Doctors Without Borders prior notification of a deadly airstrike on its field hospital in Kunduz, the aid group said on Wednesday, in an apparent violation of the Pentagon’s own instructions on the rules of war.

“We had not received any warning of the strike,” said Jason Cone, US executive director of the charity – also known as Médecins sans Frontières – five days after the Saturday morning US strike that killed 22 staff and patients and injured 37 more.

Barack Obama called MSF’s international president, Joanne Liu, on Wednesday morning to apologize for the air strike, the White House said.

The president called Liu “to apologize and express his condolences for the MSF staff and patients who were killed and injured”, according to Obama’s secretary Josh Earnest.

“The president assured Dr Liu that the Department of Defense investigation currently underway would provide a transparent, thorough and objective account of the facts and circumstances of the incident and that, if necessary, the president would implement changes that would make tragedies like this one less likely to occur in the future,” Earnest said.

But MSF intensified its pressure on the US by calling for an independent – and unprecedented – inquiry into the incident, arguing that the US, Nato and Afghan forces could not be relied on to investigate themselves.

“This was not just an attack on our hospital – it was an attack on the Geneva conventions. This cannot be tolerated,” said Liu.

International experts have told the Guardian that the question of whether an advance warning was given would be critical in determining if US forces had committed a violation of international humanitarian law.

A 2015 Pentagon manual on adherence to the rules of war explicitly requires such notification.

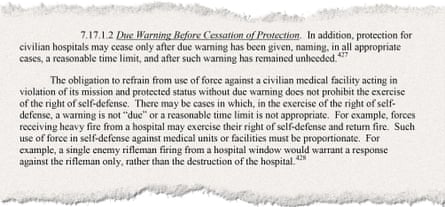

“[P]rotection for civilian hospitals may cease only after due warning has been given, naming, in all appropriate cases, a reasonable time limit, and after such warning has remained unheeded,” reads a section of the June 2015 Department of Defense law of war manual.

Protections for hospitals, a longstanding principle of international humanitarian law, would only lift if the hospital was used as a staging ground for attacks – something MSF has emphatically denied occurred in Kunduz. Yet even if the protections lifted, the Pentagon manual does not permit the hospital to come under general attack, instead requiring distinction and “proportion” to the threat.

“Such use of force in self-defense against medical units or facilities must be proportionate. For example, a single enemy rifleman firing from a hospital window would warrant a response against the rifleman only, rather than the destruction of the hospital,” the manual states.

MSF have described patients burning to death in their beds during the US airstrikes.

Colonel Brian Tribus, a spokesman for the US military in Afghanistan, did not answer a question about any US warning to the hospital, saying: “The incident is under investigation.”

But MSF have rejected the ongoing investigations by the US, Nato and the Afghanistan government as insufficient, as all are parties to the conflict.

Speaking in Geneva, Liu called for a non-prosecutorial inquiry by the International Humanitarian Fact-Finding Commission, or IHFFC, a never before-used investigative under the Geneva conventions.

Such an investigation was especially important “given the inconsistencies in the US and Afghan accounts of what happened over recent days”, Liu said.

Liu said the group intended to “reassert the protected status of hospitals in conflict”, framing the international response to the US bombing of the Kunduz hospital as a critical moment for the laws of war.

“If we let this go, we are basically giving a blank cheque to any countries at war.”

Cone said MSF is awaiting responses to letters it sent on Tuesday to 76 countries that signed the additional protocols to the Geneva conventions. Only one of them is required to prompt an inquiry by the commission, which is not an arm of the United Nations. The United States is not a party to the additional protocols.

A war of wording

The commander of US forces in Afghanistan, General John Campbell, told a US Senate panel on Tuesday that although US special operations forces on the ground in Kunduz called in a US AC-130 gunship strike on the hospital, following an Afghan request for assistance, “we would never intentionally target a protected medical facility”.

“Protected” is a critical word for any war-crimes investigation. But the Afghans have said that Taliban fighters fired on their forces from within hospital, which would potentially compromise its protected status. MSF has unequivocally denied that there was any firing from inside its hospital. Campbell, in his Senate testimony, said US personnel were not under fire and stopped short of saying that Afghan forces had received fire from the medical facility.

But should the US special operators or AC-130 crew have believed the hospital was a legitimate target, international law still requires them to provide notification to personnel within that a strike was to take place, according to experts.

“Any serious violation of the law of armed conflict, such as attacking a hospital that is immune from intentional attack, is a war crime. Hospitals are immune from attack during an armed conflict unless being used by one party to harm the other and then only after a warning that it will be attacked,” said Mary Ellen O’Connell of the University of Notre Dame.

“Hospitals and medical personnel have specific protections that are laid out in the laws of war,” agreed Sarah Knuckey, an international lawyer and professor at Columbia Law School.

“If the Taliban were attacking from the hospital, the building site would lose its protected status. But that doesn’t mean the US or Afghanistan have carte blanche to attack the facility.”

As recently as 29 September, MSF communicated the GPS coordinates of the hospital, which it has used for the past four years, to the US and Afghan governments.

Cone said it was possible that Taliban fighters received treatment for wounds within the hospital, “but they’re not combatants anymore once they’re wounded. The same could be said for American soldiers or any of the parties to the conflict, Afghan soldiers. This is a very defined, well-established and accepted principle that goes back as far as any laws of war have been accepted”.

There is some debate among lawyers about the extent to which an insurgency such as Afghanistan’s technically constitutes an international armed conflict – and accordingly whether the duty to warn applies.

IHFFC: ‘We have activated ourselves’, but options limited

The IHFFC’s president, Gisela Perren-Klingler, said she received MSF’s request for an investigation on Tuesday night and had already been in touch with the US and Afghan governments, offering the commission’s services.

“We have activated ourselves but we cannot go on mission without being asked in by a member state, and MSF is not a state,” Perren-Klingler, a Swiss doctor specialising in the treatment of psychological trauma from conflict, told the Guardian. She said the commission has also been in touch with some of America’s Nato allies to seek support for its request, and would seek to build support in public opinion.

“What we are saying is that we are the only permanent, independent, commission for international humanitarian law. Our report will be confidential and goes to both governments concerned. We are not an accountability mechanism, so we are different from the ICC [International Criminal Court].”

However, since it was first established in 1991, the IHFFC has never once been on a fact-finding mission because it has never secured the agreement of the warring parties involved in any incident it has sought to investigate. Its 15 members, who include diplomats, military officers, medical doctors and legal academics, have full-time jobs in their countries of origin around the world, and their involvement – if a mission ever went ahead – would depend on their availability.

MSF’s call for an investigation was supported on Wednesday by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), which said it would welcome any impartial probe into what happened in Kunduz.

“We have always been supportive of the IHFFC. If it can help to clarify the facts surrounding this tragic incident which led to the deaths of medical staff and patients in a health care facility, which should be protected under the laws of armed conflict, that would be a positive development,” said Helen Durham, the ICRC’s director of international law and policy.

Liu, the MSF president, acknowledged Obama’s apology late on Wednesday

afternoon.

“We received President Obama’s apology today for the attack against our trauma hospital in Afghanistan,” she said. “However, we reiterate our ask that the U.S. government consent to an independent investigation led by the International Humanitarian Fact-Finding Commission to establish what happened in Kunduz, how it happened, and why it happened.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion