Paula Keogh never intended to write about her relationship with Michael Dransfield, one of the most prominent – and colourful – poets in Australian literature.

“I was actually doing a PhD on Michael’s poetry,” she tells Guardian Australia. “And my supervisor discovered that Michael and I had known each other and been very close, and she said, ‘Hang on, I don’t know whether you’re writing the right thesis here, maybe you should write a memoir!’”

That memoir, The Green Bell, will be released in March and gives a rare insight into Dransfield’s personal and creative life, and his struggle with addiction, as well as the indignities of psychiatric care in the 1970s.

Keogh met Dransfield in Canberra hospital in 1972. She was 22 and had been admitted for psychosis and grief after breaking down in a university lecture shortly after the death of her best friend. Dransfield was admitted days later, for treatment of his drug addiction. He was working at the time on the poems that would make up his fourth collection, the acclaimed Memoirs of a Velvet Urinal.

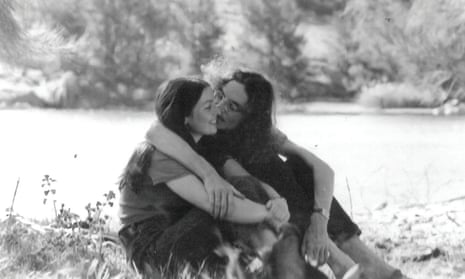

Their connection was sudden and intense, built on a mutual love of poetry and music, and a shared sense of the importance of imagination and language in shaping the world.

Dransfield, Keogh says, was able to “build a bridge” into her “very vivid inner world” and they were soon spending most of the day in each other’s hospital rooms and sneaking off its grounds together to talk and daydream beneath the canopy of a riverside willow – the “green bell” from which the book takes its title.

Keogh was hesitant to write about her experience in the hospital but, once she started, she couldn’t stop. “There’s so much that’s unsayable and unspeakable about it but, when it comes time for the story to be told, it takes over.”

One of the remarkable aspects of Keogh’s writing is her ability to capture the voice of her illness, the way it felt to be unwell. The kinds of thinking and the sensations of her illness are a strong presence in the book: she describes her head as “full of noise coming from somewhere else” and the blinking eyes of the people around her as “communicating in code”.

This voice, Keogh says, began as a series of “intrusions” into her narration of the story but soon took it over – and made the process of writing very difficult at times.

“I had to get up from the table and walk quickly around Merri creek [near her home in the inner-north of Melbourne],” she says, “because the surge of imagery and the memories that came back, that feeling of fragmentation, was really a bit of a shock to me.”

Yet Keogh believes that writing about these experiences with the distance of time was healing and allowed her to give a voice to her younger self and make sense of her experiences.

Language has always been integral to this process for Keogh. When discussing her diagnosis in the book, she writes that there are “words that are trees and words that are sores” – words, that is, that give us roots and shelter, and words that cause us pain. The word “schizophrenia”, she believes, does the latter because “it describes a set of symptoms that psychiatry wants to eradicate.

“But those symptoms are myself … it’s my self that’s affected, so to be called schizophrenic was overwhelming to me.”

Instead, she prefers the word “mad”, a word that always felt more fitting, more freeing, more like a tree.

But there’s another kind of madness at work within the book: Keogh claims that love, too, is a kind of madness, because it is “an altered state” that also involves an intense kind of imagination. This was certainly at play when she met Dransfield in the hospital – Keogh describes him as taking on “quite a mythic dimension” in her imagination. “I could see him as one of Tolstoy’s revolutionaries, or a knight,” she says. “He just had this resonance for me.”

Indeed, when Dransfield first appears in the book, Keogh portrays him as Christ-like, lying on a tree branch with his arms spread, as if being crucified. This mythologising meant that as she left the hospital and started recovering from her delusions, she had to adjust to seeing him “in his reality and not in terms of the lens I was seeing him through, with his own desperations and suffering”.

There is a great deal of suffering in The Green Bell, both Michael’s and Paula’s, and both characters are also keenly aware of the pain and discomfort that their illnesses cause the people who they love. Yet the book is uplifting and wonderfully hopeful – survival, the overcoming of suffering and the poetry of the ordinary, more everyday world, are its true driving forces.

Keogh summarises these forces by referring to one of Dransfield’s poems, which was, she says, “written on the night of his father’s death” and which claims:

there are no artists

only

who love

who sufferaround them

light

It’s not hard to see that the same kind of radiance illuminates this beautiful book.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion