While she was recuperating from a skiing accident in 2013, Angela Merkel picked up a 1,500-page tome on the 19th century by the historian Jürgen Osterhammel called The Transformation of the World. The book left an impression. A few months later she invited Osterhammel to her 60th birthday party, not just to celebrate but to give an hour-long lecture.

The theme was “history and time”, and those familiar with Osterhammel’s work detect his influence in Merkel’s worldview, particularly where he covers globalisation, migration and technology.

The admiration is mutual. “Even though I am not a member of the CDU [Christian Democratic Union] and an old SPD [Social Democratic party] voter, I am a personal fan of the chancellor,” Osterhammel said in an email exchange with the Guardian.

“Few people are likely to have read my book from beginning to end,” Osterhammel admits. “They don’t have to, and I hope the chancellor didn’t. There are many other important books to learn from. The amazing thing is that senior politicians do read history books at all.”

The historian rejects the idea that his book has had a direct influence on Merkel’s policies. But many sections of the work – on globalisation, migration and technology, to name a few pertinent topics – read differently in the light of decisions she has made since reading it, such as the treatment of Greece at the height of the eurozone crisis.

If Europe was able to pull ahead of China economically in the 19th century, Osterhammel argues, it was because the Chinese empire was hampered by a “chaotic dual system” of silver and copper coins, while much of Europe had created a “de facto single currency” with the Latin monetary union of 1866.

From a few brief conversations with Merkel, Osterhammel says he can see “she is very serious about the way world order (or disorder) has been evolving in the long run. She seems to understand, for instance, that migration and mobility have a historical dimension.”

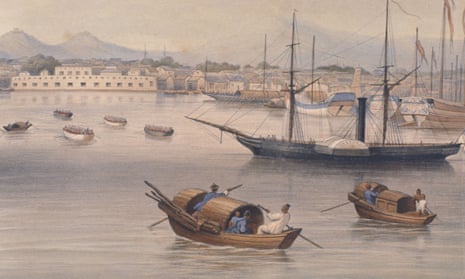

The 19th century is often described as an era of rising nationalism, a period in which states across Europe first began to develop distinct ideas about their identity. Osterhammel, a professor at Konstanz University, who wrote his dissertation on the British empire’s economic ties with China, instead recasts the century as one marked by globalisation, with 1860-1914 in particular “a period of unprecedented creation of networks” that were later torn apart by two world wars.

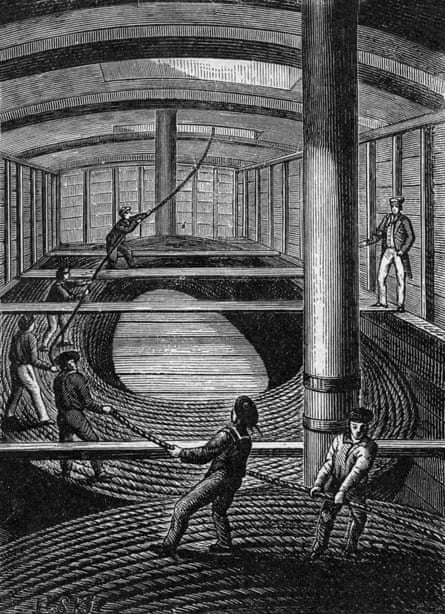

First published in 2009 and translated into English in 2014, The Transformation of the World charts how technological innovations, such as the first telegraph cable being laid across the Channel in 1851, inspired the rise of investigative reporting that in turn changed the dynamics of politics.

Although his magnum opus is in effect a history of early globalisation, Osterhammel is cautious about using the word. “I rather prefer to talk of globalisations in the plural, meaning that different spheres of life undergo processes of extension at varying speeds, and with specific reach and intensity,” he says.

“If we cling to the concept of ‘globalisation’, we should not see it as a continuous and uninterrupted march toward an imaginary ‘global modernity’. It is a bundle of contradictory developments.

“While the economy or information may have been globalised, it has not led to a corresponding generalisation of a cosmopolitan morality, if we disregard the tiny layer of an educated and mobile elite.

“Globalisation is not a smooth and benign master process such as ‘modernisation’ used to be construed 50 years ago. It is always uneven, discontinuous, reversible, contradictory, producing winners and losers, no force of nature but manmade.”

The Transformation of the World shows how free movement between states and continents grew continuously in the first two-thirds of the 19th century, and passports, border controls and trade tariffs were only invented as Europe approached 1900.

Ironically, given that Merkel would spend much of 2014 with a British prime minister lobbying her to hem in immigration across the EU, Osterhammel’s book would have emphasised to her at the start of the year that Britain had resisted continental Europe’s xenophobic turn at the end of the 19th century, allowing foreigners to enter the country without having to register with the police.

Osterhammel, who spent four years at the German Historical Institute in London, finds many positive words for Britain’s part in developing global networks in the 1800s in general. While he says he would never go as far as saying the British empire was a good thing, “it is impossible to imagine history minus empires and imperialism”.

“The British empire was a major engine of global change in modern history. When you condemn all empires with equal vehemence, you miss at least two important points. First, the British empire was a bit less murderous than the empires of Germany and Japan in the 1930s and 1940s. And secondly, it transferred the idea and practice of constitutional government, and the rule of law, to quite a few parts of world. A brief look at present-day Hong Kong will quickly elucidate this point,” he says.

One of the book’s recurring themes is that differentiating between occident and orient is often of little use when trying to understand the 19th century, and, as an invention of the 20th century, the distinction is increasingly irrelevant again. “Both the nouveau riche vulgarity of oil-exploiting societies and the atrocities at Aleppo, Baghdad and Kabul put an end to any romantic ‘east’,” he says.

“And the ‘west’ as a transatlantic cultural formation is disintegrating before our eyes. It is being reduced to [Vladimir] Putin’s and [Recep Tayyip] Erdoğan’s bogeyman.”

If Merkel finds herself eyeing the social disruption created by digitalisation as the defining theme of a potential fourth term as chancellor, Osterhammel warns that there are “very few lessons” she would be able to find in previous eras. “Many major innovations of the 19th century took decades to mature; today, change can be incredibly rapid, not just in IT but also in biotechnology,” he says.

Political diatribes against experts and academics like him, he suggests, may be born not so much of genuine disdain but the realisation that politicians are more reliant on them than ever. “Politicians find it difficult to grasp the implications of these changes. They have to rely on experts who, in turn, they deeply distrust – Angela Merkel, as a trained research chemist, less than other leaders,” he says.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion