Terri Roberts was at the theatre where she worked when the call came. It was her husband, Chuck. Terri should come straight away, he said, to their son Charlie’s house. Terri knew instantly, from the tone of Chuck’s voice, that it was serious. She didn’t ask questions, just ran to her car. And it was on the short drive that she turned on the radio and heard for the first time about a shooting incident that morning at a school in a nearby town.

Several children were dead, the report said, and the perpetrator was a man named Roy. Terri suspected immediately that the killings were connected with Chuck’s call. “I knew straight away that the school they were talking about was very near the place where our son Charlie used to park the milk van he drove,” she says. “I was imagining all sorts of dreadful things, like that he had been killed while helping to rescue some of the children. I knew he’d have helped them if he possibly could.”

Terri thought she was imagining the worst: in fact, the worst would turn out to be infinitely more appalling. When she arrived at Charlie’s house the first people she saw in the driveway were Chuck and a police officer. She remembers what happened next as if it was in slow motion.

“I said to the officer, ‘Is my son still alive?’

He said no.

Then I turned to Chuck, whose eyes were sunk deep into his face, and he said to me: ‘It was Charlie. He killed those children.’”

The next few hours were a blur to Terri. She remembers the initial disbelief, the feeling that it was utterly impossible that her lovely son, her quiet, deep, complicated but loving son, who had three young children of his own, could possibly be responsible for such an unthinkable tragedy. Hadn’t she heard the name Roy on the radio? And then, as it gradually dawned on her that what Chuck had told her must somehow be true, and that the Roy mentioned on the radio had simply been a mistake, she remembers falling to the floor and lying there in a foetal position, and howling. Just howling.

In many ways, the most extraordinary part of Terri’s story is that she isn’t metaphorically on that floor howling still. The details of the slaughter for which her son was responsible for are hard to write, hard to read and almost impossible to imagine or to begin to understand.

Here are the facts: on the morning of 2 October 2006, Charlie Roberts, carrying a gun, walked into the classroom of an Amish school near his home in Pennsylvania. He ordered the boys to leave and, half an hour later, shot 10 of the girls before turning the gun on himself. Five died: the youngest two were seven, the oldest was 12. Two of them, Lena and Mary Liz Miller, aged eight and seven respectively, were sisters. Five more girls were injured, including six-year-old Rosanna King who was initially not expected to survive and who has severe brain injuries.

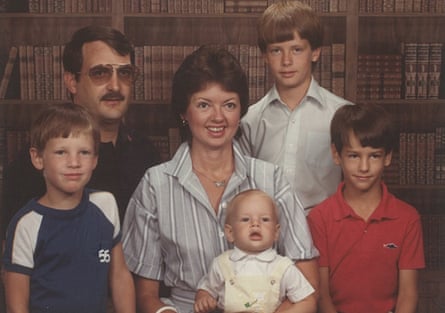

How do you begin to understand that your child has been responsible for a tragedy of this magnitude? Like Eva Khatchadourian, the mother of the killer in Lionel Shriver’s novel We Need to Talk About Kevin, Terri has combed through every detail, every nuance, every memory, every clue, to try to work out what in her eldest son’s past could have made him walk into that schoolhouse that day. “What did I miss?” she asks in her newly published book. “I was – always will be – his mother. Surely if anyone could spot signs of trouble it would be the woman who gave birth to him. At what point did bitterness begin to seethe beneath the surface contentment? Or hate tug harder at the mind and heart than love?”

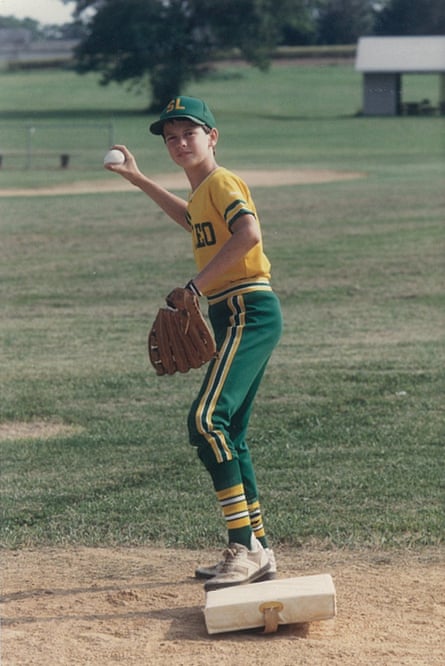

As a mother, she says, she cannot stop loving her son – and as she unravels his story – the ordinary story of an ordinary boy in an ordinary town whose life ended so violently – you feel she is doing what any parent can and must do, even in the face of odds as great as these, which is to see the very best in her child, to give him the benefit of every doubt, to put every tale in the most sympathetic light. Yet, when she has finished describing how sweet a baby he was, and how he had to cope with being born with club feet, and his learning difficulties, and the loss of his first child soon after her birth, the question hangs in the air between us, and Terri is brave enough, through her tears, to name it and answer it herself. “I ask myself, were these things related to what happened? But the truth is that plenty of people in the world have experienced extreme pain and suffering, and have coped with it. They didn’t go on to commit terrible crimes like Charlie did.”

After the murders, a note was found in which Charlie confessed to having sexually assaulted two young female relatives 20 years earlier and said he was still haunted by it. Yet, says Terri, police investigations never found any evidence that what he had confessed to had, in fact, happened.

Looking back, she can see that Charlie was always quiet as a boy. “But I have a husband who is quiet and another son who is quiet. It’s not unusual for men to be quiet.”

Could there really have been no sign that Charlie was disturbed at a very deep level? Terri is adamant that there were not. “After it happened, I got together with his best friend and we talked. He said, ‘I never saw anything in Charlie that would have brought him to anger or resentment. It just wasn’t there …’ The only thing I can say is, he obviously masked hurt deeper than I could ever have imagined. So yes, as a mother I wish – how much I wish – I had drawn him out more. If I have any message for other mothers, it’s this: if you have a child who is quiet and reserved, especially when hard things happen, it’s worth reflecting with them to see if there’s anything deep that needs to come to the surface.”

The truth is, and Terri knows it, that whatever terrible things were going on inside Charlie, they were probably too deeply buried for anyone else to access. “Somewhere in my son’s life he experienced some kind of pain that he internalised and never shared with anyone. He internalised something so painful that it opened up a door for evil. Something grabbed hold of him that was so dark and so deep.”

Terri is a Christian – she raised Charlie as a Christian – but since the tragedy she has had some big questions. “I’ve said to God, I simply don’t understand how you could let it happen. You could have given his car a flat tyre. In the end, I’ve had to admit that there can be no understanding. I’ve chosen to trust God because there’s nothing else I can do. I have no understanding of why.”

Of course, there have been times when she has burned with anger at Charlie. How, she asks in her book, could he have done this? “How could he … leave his wife a widow, his children fatherless? Leave them to face the shame and the horror? And the gentle Amish families he had come to know so well in his rounds collecting milk. What darkness and evil could so possess his mind that he would want to hurt them? To rip away daughters as precious as his own? To inflict such pain and loss on another living soul?”

After the shooting, and especially in the early days afterwards, Terri was acutely aware of how she, as Charlie’s mother, and the whole of their family, was being judged and seen by others. “It was scary,” she says. “Knowing we were being labelled. In some ways it was harder for Chuck than for me – he’s a retired police officer. He even has the same name as Charlie, so when he was showing his driving licence or something, people would do a double take and he’d have to say, ‘Yes, that’s right, I’m the father,’”

Even going out shopping, or anywhere in public, meant they would be looked at, pointed at, blamed. Then something truly extraordinary happened – something that injects a glimmer of hope and faith and goodness into a story that is otherwise laced with horror and heartache.

Charlie’s funeral was difficult for his parents and his wife, Marie, to organise: what undertaker, after all, would want to handle the burial of a man so loathed? Eventually, though, it was arranged. The family braced themselves for a media barrage. As they walked through the churchyard, Terri remembers, she could see the telescopic lenses trained on them. “We felt vulnerable – we knew everyone was looking at us. Then, from behind a shed, a group of Amish people appeared, men in tall hats and women in white bonnets. They fanned out into a line between the graveside and the road. They were protecting us from the media.”

There was more. “When the service ended, these people came forward, these lovely people whose eyes, like mine, were red with tears. The first ones to approach us were Chris and Rachel Miller, whose daughters Lena and Mary Liz had both died in their arms. And they said to me: ‘We are so sorry for your loss.’

“There are no words to describe what it feels like when people who have suffered so much at the hands of your son reach out and say something like that, says Terri. “It was an amazing thing to know that through their suffering they wanted to comfort us.”

Forgiveness, she says, is a choice. “These sweet parents were still as grief-stricken as I was, their hearts broken like mine over the loss of their children. But they had chosen to forgive instead of hating – to reach out in compassion instead of anger.”

As time went by, there were further opportunities for Terri to connect with the Amish community and one day a chance came to visit Rosanna, the little girl who had pulled through, but with brain damage.

“I felt a need, a motherly need I guess, to connect. It was about two months afterwards, and I was invited to the house. They welcomed me in and gave me a seat next to Rosanna who was there in her wheelchair. She was so sweet and she had been so disabled; it was quite an emotional experience. I managed to hold myself together while I was there, but when we left I just started to bawl. To know that my son was responsible for this …”

There were more visits to Rosanna’s family and eventually something even more incredible happened. Terri noticed that the family – who also had three young sons – found it difficult to eat together because someone had to be with Rosanna, so she asked whether she could help by looking after her while the family ate. For several years she went once a week and, these days, still visits regularly, even though she is no longer in good health. “I had breast cancer some years ago and now it’s in my lungs,” she says.

She will go on visiting Rosanna, now 16, for as long as she can. “She is very dear to my heart,” says Terri. “She’s become almost like a granddaughter.”

In the end, she says, there are no words to describe what happened, just as there is no explanation. But if the shooting in the Amish school that day represented the unthinkable, then what has taken place since seems to represent what might be called a miracle.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion