The Unintended Consequences of Purity Pledges

A new study suggests teens who vow to be sexually abstinent until marriage—and then break that vow—are more likely to wind up pregnant than those who never took the pledge to begin with.

Teen birth and pregnancy rates have been in a free fall, and there are a few commonly held explanations why. One is that more teens are using the morning-after pill and long-acting reversible contraceptives, or LARCs. The economy might have played a role, since the decline in teen births accelerated during the recession. Finally, only 44 percent of unmarried teen girls now say they’ve had sex, down from 51 percent in 1988.

Teens are having less sex, and that’s good news for pregnancy-and STD-prevention. But paradoxically, while it’s good for teens not to have sex, new research suggests it might be bad for them to promise not to.

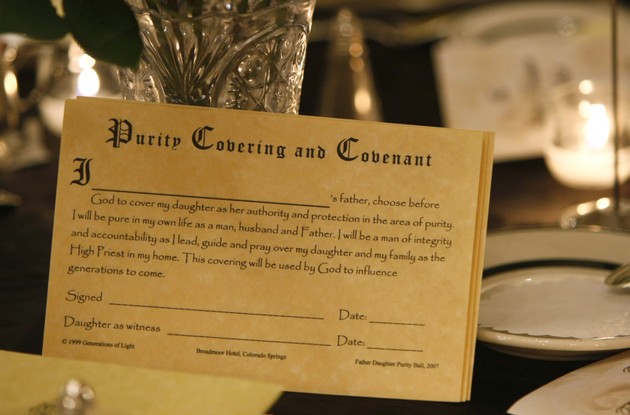

As of 2002, about one in eight teens, or 12 percent, pledged to be sexually abstinent until marriage. Some studies have found that taking virginity pledges does indeed lead teens to delay sex and have fewer overall sex partners. But since just 3 percent of Americans wait until marriage to have sex, the majority of these “pledge takers” become “pledge breakers,” as Anthony Paik, a sociologist at the University of Massachusetts–Amherst, explains in his new study, which was published in the Journal of Marriage and Family.

Paik wanted to see what happens if and when these teens break their pledges. He and his co-authors relied on interviews with thousands of teens conducted as part of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health in 2002 and 2008. The results showed that women who did or did not take abstinence pledges were equally likely to get HPV—about 27 percent of each group would eventually contract the virus, which causes genital warts. Among women who had multiple sexual partners, however, pledge breakers were more likely to get HPV.

The results were even more striking for out-of-wedlock pregnancy: About 18 percent of the girls who had never taken virginity pledges became pregnant within six years after they began having sex. Meanwhile, 30 percent of those who had taken a pledge—and broken it—got pregnant while not married.

Paik explains this in part through the phenomenon of “cultural lag” —the idea that people might reject certain values faster than they update the actions supporting those values. In this case, the pledge breakers abandoned the idea that they should be virgins until marriage, but unlike people who never made the pledges, they didn’t use birth control and condoms, Paik theorized. (Many sex-ed programs and cultures that promote abstinence only until marriage also teach that contraceptives are ineffective.)

“Our research indicates that abstinence pledging can have unintended negative consequences by increasing the likelihood of HPV and non-marital pregnancies, the majority of which are unintended,” Paik said in a statement. “Abstinence-only sex education policy is widespread at the state and local levels and may return at the federal level, and this policy approach may be contributing to the decreased sexual and reproductive health of girls and young women.”

That doesn’t mean that people who have a genuine motivation to save themselves for marriage shouldn’t do so. A previous study found that the key to a virginity pledge’s success seems to be the pledger’s level of religious commitment. Devout pledgers had fewer sexual partners, but pledgers who weren’t very religious engaged in riskier sexual behaviors than those who didn’t pledge.

Perhaps that’s why the vow in True Love Waits, the original virginity-pledge program, reads the way it does: “I make a commitment to God, myself, my family, my friends, my future mate, and my future children to a lifetime of purity including sexual abstinence from this day until the day I enter a Biblical marriage relationship.”