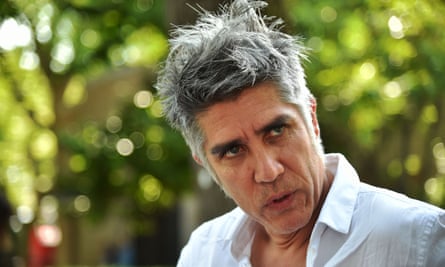

“The only animal that can defeat the rhinoceros is the mosquito,” says Alejandro Aravena, the Chilean architect curating this year’s Venice architecture biennale. “Or a cloud of mosquitos, actually.”

He is standing in the former rope factory that serves as the exhibition’s main venue, a 300-metre-long promenade of installations, where robotically milled stone vaults compete with teetering bamboo frames, made by dozens architects from far-flung corners of the world. These are Aravena’s mosquitoes.

“Architects often think they are too small to make a change, but together they can smother the big animal.”

The beast in question is the capitalist machine, responsible for the slew of “banality and mediocrity” in our built environment. It’s one of the battlegrounds Aravena’s biennale aims to tackle, along with migration, segregation, traffic, waste and pollution, and a host of other “urgent issues facing the whole of humanity”, as he puts it, “not just problems that only interest architects”.

It is a refreshing premise for the biennial bonanza, which too often indulges the rarified realms of architectural theory and form-making. But does it make for an engaging show, or a tedious traipse through holier-than-thou humanitarianism and architectural self-flagellation – the latest attempt to convince the public that designers have a conscience?

Thankfully the moralising is kept at a relatively low volume. What shines through is a dazzling range of ingenious responses to situations of scarcity and insecurity, along with a good number of beautiful things that have no worthy pretensions at all.

A display of Wang Shu and Lu Wenyu’s work near the Chinese city of Fuyang sets the tone, with tactile pallets of reclaimed tiles, crushed rubble and rammed earth laid out on the floor, showing the handmade materials used in their recent restoration of the village of Wencun. Wang was approached by the city to design a lavish cultural complex, following his Pritzker prize win in 2012, but insisted on upgrading the crumbling historic village as a condition of the project, using his trademark twist on traditional craft techniques and local labour.

This cocktail of simple, earthy materials and canny subversion of the client’s brief is a recurring theme here. There are many rugged, rustic constructions of brick, stone and earth to admire and fondle, from Paraguayan architect Solano Benítez’s parabolic brick arch to the CNC-sawn stone vaults by the Block Research Group at ETH Zurich. The former mobilises two of the cheapest and most abundant resources in the world, clay and unskilled labour. The latter is at the cutting edge of digital form-finding and robotic manufacture. Nearby stand a pair of prototype concrete slabs, modelled on gothic fan vaults, that use 70% less material than a conventional flat slab – and are a good deal prettier.

“We shouldn’t forget beauty in our battles,” says Aravena, who is keen that his show should not simply be taken as a “biennale of the poor.” His own work on low-cost housing in Latin America has earned him the position of poster boy for activist architects, but his practice, Elemental, is as obsessed with achieving the perfect finish of poured concrete on its expensive commercial buildings as it is with revolutionising models of affordable housing. The biennale reflects this, which means, at times, it can feel a little erratic.

In the Central Pavilion, German architect Anna Heringer has crafted an alluring earthen cocoon (or “mud nugget” as she calls it) with Martin Rauch and Andres Lepik, that makes you envious of earthworms, tempting you to curl up inside its womblike form. More eye candy and guilt-free architectural indulgence comes in the form of Raphael Zuber’s shrine of bronze models, Renato Rizzi’s exquisite plaster casts and Aires Mateus’s elegant studies in form and light. Their rooms are a welcome salve after some of the more challenging work on show, places you might go to recover from the perilous battlegrounds that other exhibitors are confronting head on.

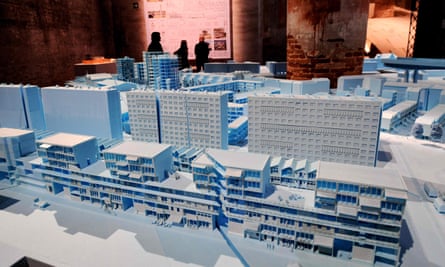

One of the most powerful confrontations comes from Forensic Architecture, an NGO led by London-based Israeli architect and writer Eyal Weizman, whose team has been compiling evidence for prosecutors in the International Criminal Court and the UN General Assembly into bombing campaigns in the Middle East.

“War is now almost exclusively urban in nature,” says Weizman. “The majority of civilian casualties occur in buildings, so architects are the best-placed to offer their expertise in tracing how these events happened.”

One project demonstrates how his team analysed reams of video footage from social media of Israeli military attacks on Gaza in 2014 to prove the army was using one-tonne bombs in heavily populated residential areas, resulting in high civilian casualties. By overlaying images of bomb clouds from multiple viewpoints, they generated a 3D model and triangulated the exact location of the strike.

The centre of their space is occupied by a full-scale mock-up of a room bombed-out from a US army drone strike drone attack in Pakistan, with strings extending from the shrapnel pock-marks in the walls back into the centre of the room to determine the point of explosion of the bomb. The model proves the damage was the result of an “architectural missile”, capable of being detonated on a specific floor of a building, while the “shadows” – where there are no shrapnel marks – denote the locations of the victims killed in the attack.

This forensic process – what Weizman calls “architecture in reverse” – shows how the analytical and presentational skills of architects can be deployed in graphic, damning detail, in circumstances that extend way beyond the comfort zone of the drawing board. Forensic Architecture’s 3D-printed bomb clouds also feature in a satellite exhibition organised by the V&A. Curated by Brendan Cormier, A World of Fragile Parts investigates 200 years of copying since the museum’s first director Henry Cole wrote the charter on Reproductions of Works of Art to encourage the international exchange of copies between museums.

Cormier calls it “the first manifesto for sharing”, and his team has mined a rich seam of reproductions from the museum’s archive as well as unearthing inventive contemporary takes on copying, from the Institute for Digital Archaeology’s reproduction of part of the Palmyra arch, destroyed by Islamic State, to Sam Jacob Studio’s model of a temporary shelter from the Calais “jungle” refugee camp, digitally milled from artificial stone.

The monumental rendering of such a flimsy, ephemeral structure stands in poignant contrast to another refugee encampment on show, which occupies an ambiguous place in Venice’s Giardini between the national pavilions and the central pavilion.

“The ambiguity is no accident,” says Manuel Herz, who has been researching the urbanism of the Western Sahara’s refugee camps for the last decade. “By positioning the pavilion here I am staking a claim for their nationhood.”

A former Spanish colony, occupied by Morocco since 1975, the Western Sahara remains a contested zone, on whose fringes 160,000 Sahrawi refugees live in camps that have taken on the structure of formalised towns. A series of hanging carpets, woven by the National Union of Sahrawi Women, together with photos by Iwan Baan, explain the architectural structure of these informal towns, which have developed schools, cultural facilities, ministry buildings and even their own parliament – decorated with jazzy giraffe-patterned walls. “If they were western architects they would have won the Pritzker prize by now,” says Hertz, who has revealed a peculiar sculptural beauty in their low-key provisional buildings, which speaks of the powerful national pride of a state in exile.

For all of this provocative work from the lesser-known fringes of architectural culture, there are also the usual suspects, who feel like they’ve been included out of deference to age and stature rather than because they have anything meaningful to add. Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano feel particularly out of place, using their rooms as corporate showcases to display their greatest hits.

An opportunity has also been missed to cast the net further beyond the profession and bring in more voices from the worlds of planning and property development, lawmaking and governance- – the real forces that shape our cities. Where the work of public authorities is featured – such as in a transformative public space initiative in the crime-ridden Colombian city of Medellin – the results err on the stodgy side, as if lifted from a generic conference on city marketing.

While Aravena’s initial rallying cry hinted that he might be radically reinventing the biennale format, cracking open the hermetic architectural club to let the real world flood in, there is still too much of the usual fodder, too many exhibitors resorting to the default setting of enigmatic installation and video without much substance. It is to be expected given the time constraints: Aravena had just 10 months to pull the show together, less than half the time the previous director Rem Koolhaas demanded.

Still, with a little patience, there are enough mosquitoes with bite to be found in the swarm, providing optimism that the rhinoceros may yet be toppled.

- This article was corrected on 1 June 2016. Forensic Architecture’s project was wrongly cited as being about US strikes on Afghanistan, when it was actually about Israeli attacks on Gaza

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion