jonathan: perhaps AndrewC should have to use OS 9 for a day or two ;)

LeeH: omg

LeeH: that's actually a great idea

The above is a lightly edited conversation between Senior Reviews Editor Lee Hutchinson and Automotive Editor Jonathan Gitlin in the Ars staff IRC channel on July 22 of 2014. Using Mac OS 9 did not initially seem like such a "great idea" to me, though.

I'm not one for misplaced nostalgia; I have fond memories of installing MS-DOS 6.2.2 on some old hand-me-down PC with a 20MB hard drive at the tender age of 11 or 12, but that doesn't mean I'm interested in trying to do it again. I roll with whatever new software companies push out, even if it requires small changes to my workflow. In the long run it's just easier to do that than it is to declare you won't ever upgrade again because someone changed something in a way you didn't like. What's that adage—something about being flexible enough to bend when the wind blows, because being rigid means you'll just break? That's my approach to computing.

I have fuzzy, vaguely fond memories of running the Mac version of Oregon Trail, playing with After Dark screensavers, and using SimpleText to make the computer swear, but that was never a world I truly lived in. I only began using Macs seriously after the Intel transition, when the Mac stopped being a byword for Micro$oft-hating zealotry and started to be just, you know, a computer.

So why accept the assignment? It goes back to a phenomenon we looked at a few months back as part of our extensive Android history article. Technology of all kinds—computers, game consoles, software—moves forward, but it rarely progresses with any regard for preservation. It's not possible today to pick up a phone running Android 1.0 and understand what using Android 1.0 was actually like—all that's left is a faint, fossilized impression of the experience.

As someone who writes almost exclusively about technology at an exclusively digital publication, that's sort of sobering. You can't appreciate a classic computer or a classic piece of software in the way you could appreciate, say, a classic car, or a classic book. People who work in tech: how long will it be before no one remembers that thing you made? Or before they can't experience it, even if they want to?

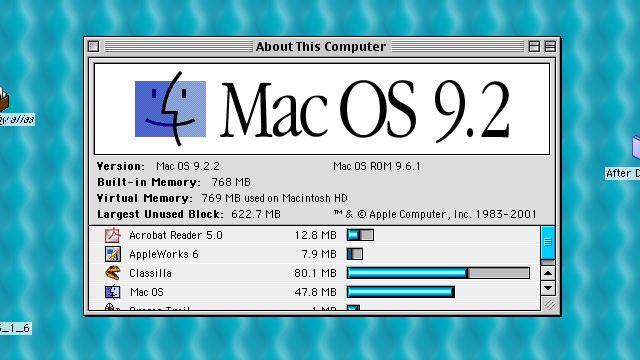

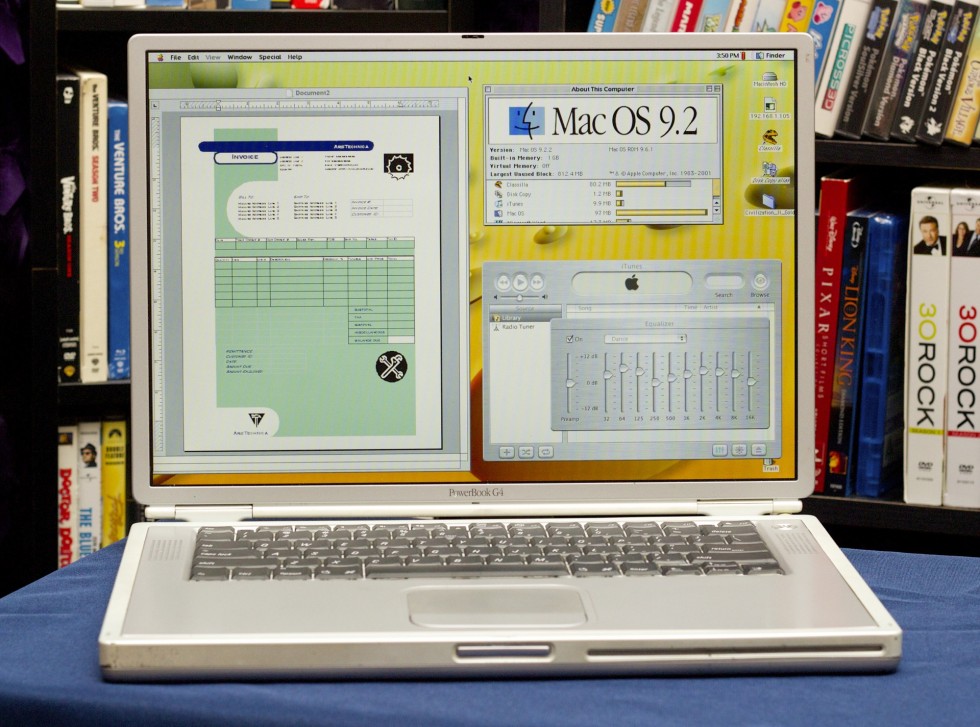

So here I am on a battered PowerBook that will barely hold a charge, playing with classic Mac OS (version 9.2.2) and trying to appreciate the work of those who developed the software in the mid-to-late '90s (and to amuse my co-workers). We’re now 12 years past Steve Jobs’ funeral for the OS at WWDC in 2002. While some people still find uses for DOS, I’m pretty sure that even the most ardent classic Mac OS users have given up the ghost by now—finding posts on the topic any later than 2011 or 2012 is rare. So if there are any of you still out there, I think you're all crazy... but I’m going to live with your favorite OS for a bit.

Finding hardware

My first task was to get my hands on hardware that would actually run OS 9, after an unsuccessful poll of the staff (even we throw stuff out, eventually). I was told to find something usable, but to spend no more than $100 doing it.

You'd think it would be pretty easy to do this, given that I was digging for years-old hardware that has been completely abandoned by its manufacturer, but there were challenges. Certain well-regarded machines like the "Pismo" G3 PowerBook have held their value so well that working, well-maintained machines can still sell for several hundred dollars. Others, like the aluminum G4 PowerBooks, are too new to boot OS 9. They'll only run older apps through the Classic compatibility layer in older versions of OS X.

I didn't want to deal with the pain of an 800×600 display, so the clamshell G3 iBooks were out, and I never really liked the white iBooks at the time—I found their keyboards mushy and their construction a little rickety. White plastic iBooks and MacBooks were never really known for their durability. Anything with a G3 also rules out support for OS X 10.5, which I'd want to install later to actually get stuff done on this thing.

The laptop I decided to go with was the titanium PowerBook G4. While these weren't without quality issues, they at least promised usable screen resolutions and Mac OS 9 compatibility. They also tend to fall right where we'd want them on the pricing spectrum—old enough to be cheap, but not so old or well-loved to be collectors' items.

Notes on that video:

- The PowerBook G4 is called a "supercomputer." You keep using that word...

- What does this music have to do with anything?

- Phil Schiller’s hair!

- Jony Ive pronounces “aluminum” in the American fashion, rather than “aluminium.”

- Titanium was better than aluminum in 2001, but it apparently stopped being that way later in the decade.

- Mac OS X had been out for about six months at this point, and it’s mentioned by name once in the ad, but all of the shots of the computer in action show it using Mac OS 9. The first few OS X releases are best forgotten.

Finding used computers on Craigslist is a great way to get scammed and left for dead in some alley in Brooklyn, so I turned to eBay. Many used computers on eBay are being sold "as-is" or for parts, a last-ditch effort by their owners to get some kind of value out of them while also getting rid of them. It's a bit risky, but you can save some money if you buy one of these dinged-up models and fix it yourself.

For about $75, I was able to pick up an 800MHz model with 512MB of RAM and a 40GB hard drive. It worked but included a non-working battery, no power adapter, and a wonky power jack. For $8.86, I picked up a new power jack (happily, it was separate from the main logic board in those days), and another $15 got me a used genuine Apple adapter (third-party substitutes are widely available for a few dollars less, but I am terrified of cheap off-brand chargers). That brought my total to a little under $100.

I could have spent between $25 and $95 on a working third-party battery. I just happened to have 1GB of PC133 SDRAM (the maximum amount supported by this PowerBook) buried in my closet, though I would have shelled out another $12 or so if I’d had to pay for it. These upgrades aren’t strictly necessary, and dumping a lot of extra money into a computer this old is unlikely to raise its value much. I did go $30 out-of-pocket to replace the rickety old hard drive with a shiny new one with a faster rotational speed and a higher capacity, though. Sometimes you’ve got to treat yourself.

My iFixit screwdriver kit and the handy iFixit repair guides helped me crack the case, replace the power jack and drive, and swap out the RAM. All repairs went off without a hitch, and I used some canned air to blow out some of the dust and grit that had gathered inside the case. I cleared my 2012 iMac off my desk and replaced it with the repaired PowerBook. Time to get to work.

reader comments

121