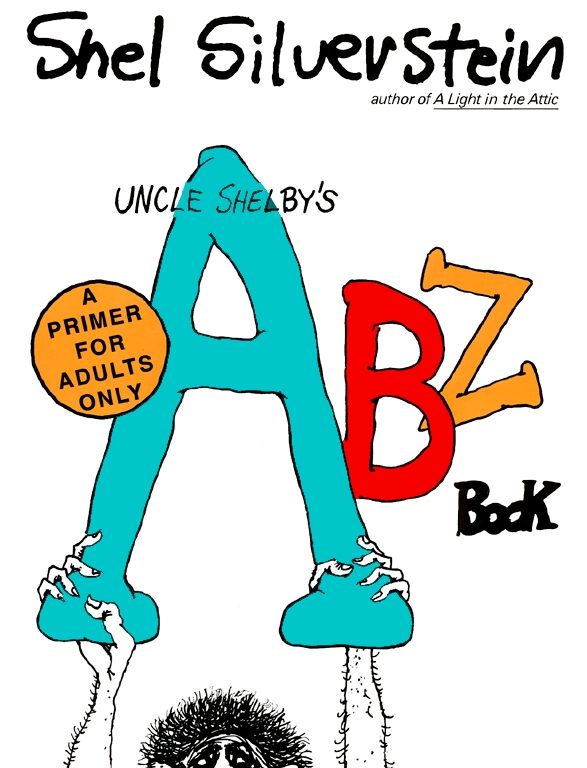

A Look Back at Shel Silverstein’s Adults-Only Children’s Book

Uncle Shelby’s ABZs teach a lot more than the alphabet.

In the August 1961 issue of Playboy, Hugh Hefner, likely recognizing that his adult publication was missing out on a lucrative and untapped market, commissioned some material just for the kids. Six pages after a centerfold spread of Playmate Karen Thompson, Playboy Magazine printed its inaugural children’s work—Uncle Shelby’s ABZ Book.

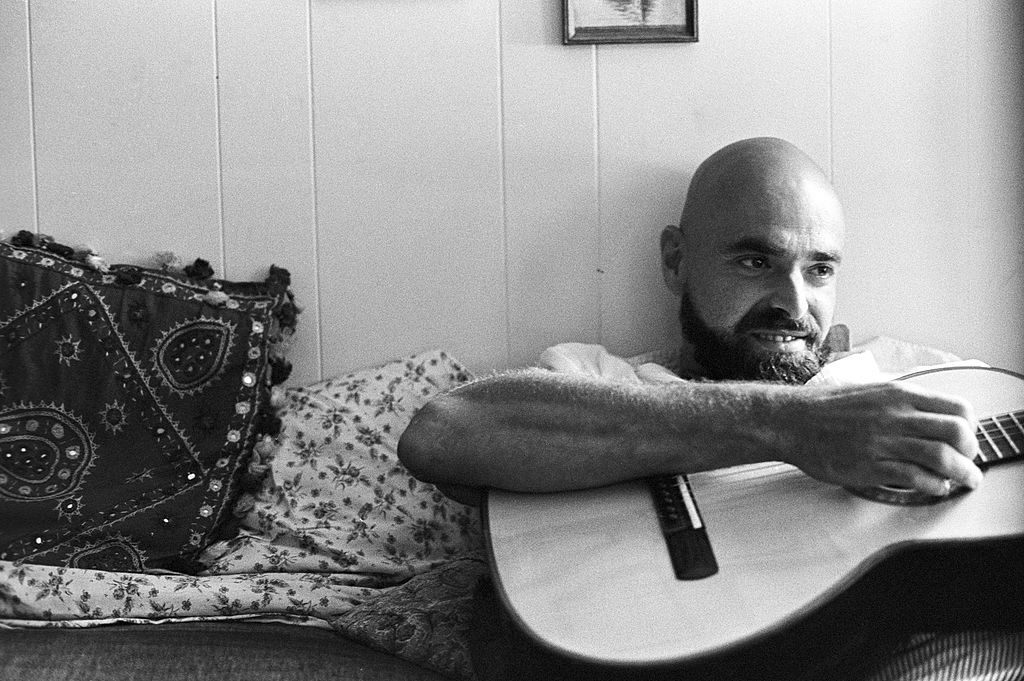

Shortly thereafter, Uncle Shelby’s ABZ Book was published. Featuring much of the material from Playboy, it was the first book written by prolific author, musician, playwright and songwriter Shel Silverstein, then Playboy’s resident cartoonist. Over the past 55 years, it has become a literary cult classic, unknown by most, but fiercely adored by ardent fans.

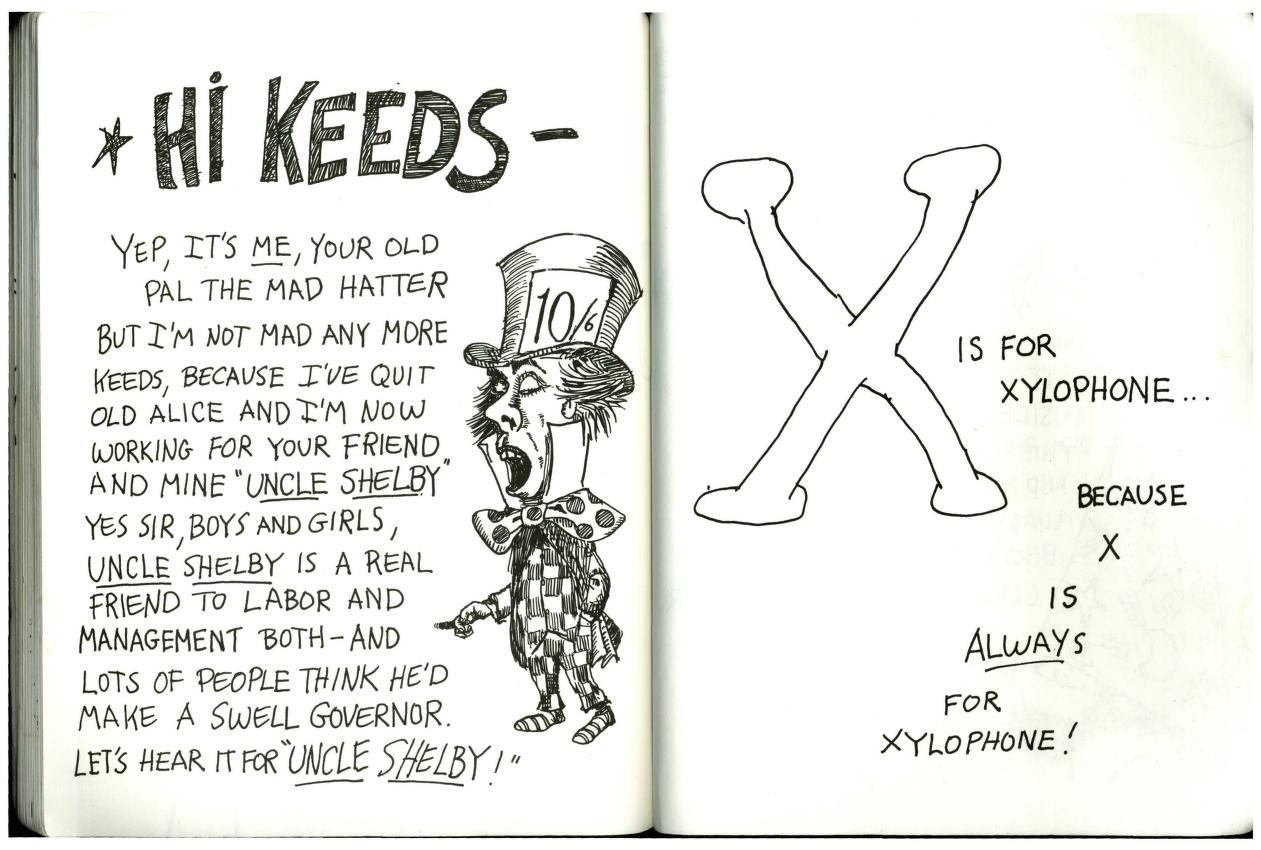

Silverstein’s introductory work purports to be an educational tool, bearing the tagline, “A Primer For Tender Young Minds.” But upon the most cursory of inspections, it becomes clear that Uncle Shelby is not to be trusted with young minds, tender or otherwise.

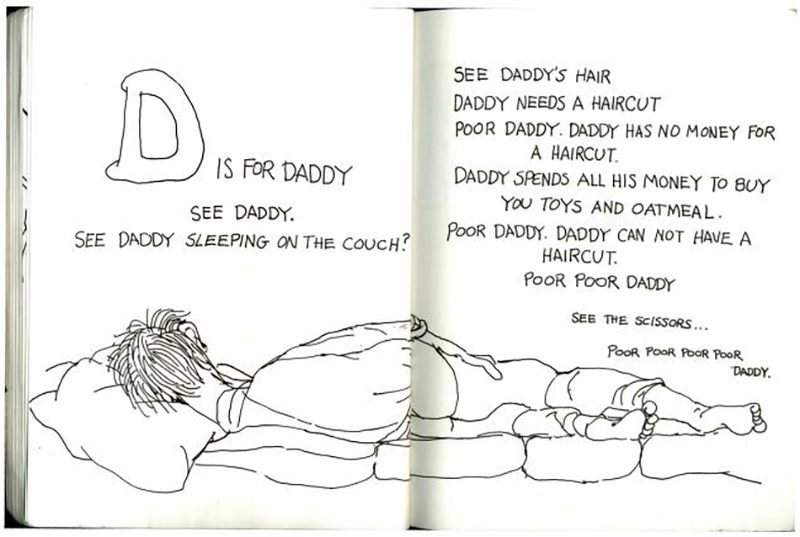

Uncle Shelby’s ABZ Book is a brazen work of satire. Borrowing from the tradition of children’s learn-the-alphabet books, Silverstein constructs a stable of mnemonic devices to help his readers take their first steps toward literacy. Unlike most alphabet books, however, Silverstein’s associations are not intended to reinforce memory, but to prey upon the insecurities of children, suggest mischievous misdeeds, and otherwise exploit the ignorance—er, innocence, of youth.

Following all of Uncle Shelby’s mal-advice would make for an exciting episode of Jackass. This is Silverstein at his most impish—he gleefully plays the role of devil-on-the-shoulder, encouraging young readers to throw eggs at the ceiling, ask mother to purchase a gigolo, and pretend to drink lye (if you pretend to drink lye, the doctor will pump your stomach and “give you a nice red lollipop.”).

Given all of the thinly veiled adult humor throughout the book, it seems quite clear that Uncle Shelby’s ABZ Book is not intended for children. But some distracted adults, it seems, neglected to actually read it before passing it to their sweet, impressionable young ones —today’s parental equivalent of giving a child unprotected internet access. One scandalized reader on the book review site Goodreads didn’t realize her mistake until she had already begun a family reading. “The truly shocking page,” she wrote, “was where he was joking about going with kidnappers and eating the lollipops they offer.”

As a result of such misunderstandings, the current print edition, dating back to 1985, includes a stamp on the front that reads, “A Primer For Adults Only.”

Uncle Shelby’s ABZ Book is not the only work of Silverstein’s that was met with consternation from overzealous would-be book-banners. A Light in the Attic, his 1981 collection of children’s poetry, ranks 51 out of 100 on the American Library Association’s list of most challenged materials from 1990-1999 (it was also the first children’s book on the New York Times bestseller list). Some found the material offensive, citing poems that “glorified Satan, suicide, cannibalism, and also encouraged children to be disobedient.”

Uncle Shelby’s ABZ Book never attained enough commercial success to make any “most hated by parents” lists. But at least it gave anyone a worthy reason to read Playboy—for the (children’s) articles.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook