Henri Cartier-Bresson, co-founder of the famed Magnum agency, once likened the contact sheet to the analyst’s couch. “It’s all there: what surprises us is what we catch, what we miss, what disappears.”

Today, the contact sheet has all but disappeared as digital technology has rendered the analogue camera a thing of the past, beloved only of purists and a coterie of young obsessives who fetishise film and the alchemy of the darkroom.

In 2011, the publication of the photobook Magnum Contact Sheets seemed like an epitaph on the whole elaborate, hands-on process of pre-digital photography. Four years on, a new exhibition, which opens at FOAM Amsterdam on 11 September, is framed as “a tribute to analogue technique” – further evidence that what was once taken for granted is now seen as almost absurdly old-fashioned. It strikes me that many younger visitors to the show may not even be familiar with the term “contact sheet”, so swiftly has digital culture excised all traces of the process that once governed photography.

For all that, the show lets us reconsider not just what has been lost, but the discipline and rigour of analogue photography. We often speak of a photographer honing his or her eye solely through the act of shooting, but perusing contact sheets also honed the eye in terms of selecting images.

How revelatory they could be in illuminating a photographer’s creative choices was hit home to me at the great Robert Frank retrospective, Storylines, at Tate Modern in 2005. The contact sheets for The Americans showed how few frames Frank shot of each subject – just two or three slight variations sufficed. Like many great photographers, he edited in his head as he shot. The use of a contact sheet was a process of utter refinement. (How this worked for William Eggleston has intrigued me ever since he told me: “I only ever take one picture of one thing. Literally. Never two.”)

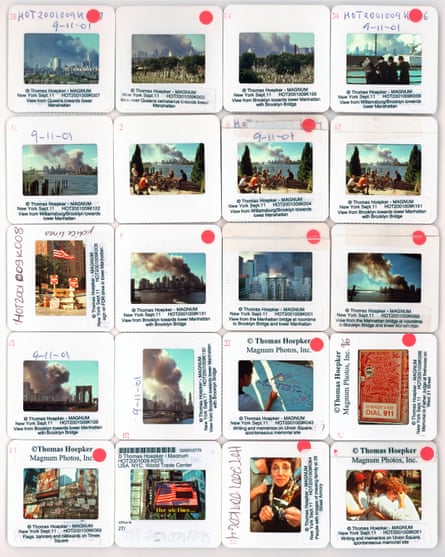

At Foam, 60 contact sheets – and the famous images picked from them – will be on show. The first is from the 1940s, three years before Magnum was established, when Robert Capa (another co-founder) was a photojournalist embedded with British troops in the second world war. As Capa’s dramatic images of the landings on Omaha Beach on D-day show, the contact sheet is evidence of how a photographer works under extreme duress.

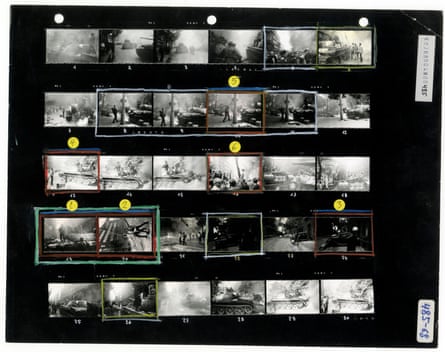

Likewise, the young Josef Koudelka’s shots of the Russian invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, taken at considerable risk on the streets of Prague. Koudelka’s contact sheets, like Capa’s, are both a record of a seismic historical moment and a diary of a frantic creative process. All the visceral energy and edginess of those first days of collective shock and turmoil are captured in photographs that are not always deftly composed or properly exposed. Koudelka was shooting on out-of-date black-and-white cinema film – the only stock available to him – and had to run back to his dark room to reload after shooting every roll.

Four years later, Gilles Peress was on the ground in Derry when British paratroopers fired into the crowd at a civil-rights march, killing 13 civilians. Peress’s contact sheets were integral to the Saville Inquiry into the Bloody Sunday shootings, helping to establish context. In her essay for the Magnum Contact Sheets book, Kristen Lubben notes how a contact sheet can offer detailed evidence, and be used to corroborate or contradict received versions of events. The single photograph may be our defining image of a historical moment, but the contact sheet shows the uncertainty and even unreliability of that moment.

At the other extreme, they can record the painstaking creation of an elaborate studio portrait. Philippe Halsman’s fittingly surreal image of Salvador Dalí is a case in point. The artist stands poised at his easel as three startled cats and a stream of water fly though the air. Here, the contact sheet proves how labour-intensive and hit-and-miss such an ambitious set-up could be – and, yes, the cats were repeatedly flung though the air by Halsman’s assistants until he got the shot he wanted.

One of the most iconic images at Foam is René Burri’s 1963 portrait of a cigar-smoking Che Guevara. It shows the victorious revolutionary as statesman, a Cuban cigar adding another layer of romantic gravitas to Guevara’s already carefully-managed image. The contact sheet shows a more restless – and more human – individual, by turns tired and expansive. Once again, it is the contact sheet, not the individual portrait, that captures the complexity of the subject.

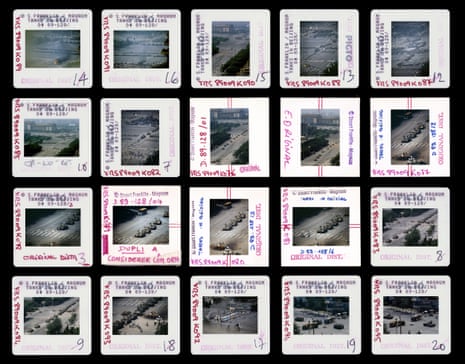

Whether showing us a second-by-second unfolding of a historical event (Stuart Franklin’s contact sheet from the Tiananmen Square protests that contained the famous “tank man” shot), or a glimpse of the mechanics of Hollywood star-making machinery (Bert Glinn’s shots of a young and sultry Elizabeth Taylor on the set of Suddenly Last Summer), the contact sheet is a repository of evidence that can reveal both a photographer’s greatness – and their fallibility.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion