Durham's Anti-Klan Block Party

Hundreds of residents came out to the streets after rumors of a white-supremacist rally protesting the removal of a Confederate statue.

DURHAM, N.C.—Friday started inauspiciously in the Bull City. A crowd of activists arrived at the Durham County Courthouse early in the morning to express solidarity with four people who had their first appearance in court, facing charges for pulling down a Confederate statue. A rumor circulated: The Ku Klux Klan was planning to head into town in response to the statue’s removal.

A group huddled outside the courthouse, planning strategy: Come at noon. Make sure there’s a critical mass of counter-demonstrators to stare down anyone who comes. Bring a gas mask if you can. There was even speculation that militiamen—two sunglass-and-hat-wearing men peeking over the parapet of a parking garage across the street—were already casing out the area. (They turned out to be sheriff’s deputies.)

A KKK march isn’t an idle threat, even though the Old North State isn’t the Klan country it once was when a billboard outside Smithfield welcomed visitors on behalf of a hooded, mounted Klansman. There is a KKK chapter in Pelham, North Carolina, about an hour from Durham, that has staged rallies before, including a July 8 rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, that foreshadowed last weekend’s larger and more violent event. As the morning progressed, rumors flew with increasing speed around social media.

By 11:45 a.m., when I returned downtown, a couple hundred people had massed on Main Street in front of the Pinhook, a hip LGBT-friendly bar. Some of them were the same people who had taken part in Monday’s protest; many more had just shown up because they were angry and worried about the Klan coming to town.

There were banners of the homemade, Sharpie-and-posterboard variety, more elaborate fabric ones, and a flag of the Industrial Workers of the World, the union most associated with Eugene Debs and the early 20th century labor movement. There were new rumors—the Klan members were driving in and had been spotted a few miles away, headed for downtown. A man with a rifle slung over his shoulder jumped up on a car. Saying he’d been with Redneck Revolt, a left-wing militia, in Charlottesville the weekend before, he exhorted the crowd, saying that if police (who were little in evidence) were unwilling to block the Klan, the people needed to do so:

But as it turned out, no Klan showed up—at least no recognizable hooded figures, and no one claiming to be a Klansman. (There was a tense encounter between the crowd and two men offering racist rhetoric, though it was eventually defused.) So with hundreds of Durhamites out on the street, a gathering convened to block the Klan threw an impromptu block party instead.

First, however, there was marching. As it became apparent that no Klan members were arriving imminently, the group decided to take advantage of having blocked traffic and to have a parade, marching around the block. People rotated through chants: “No Trump, no KKK, no fascist USA,” “Cops and the Klan go hand in hand,” and, as they passed the jail, “We see you, we love you.” (A roar of appreciation came from the jail.)

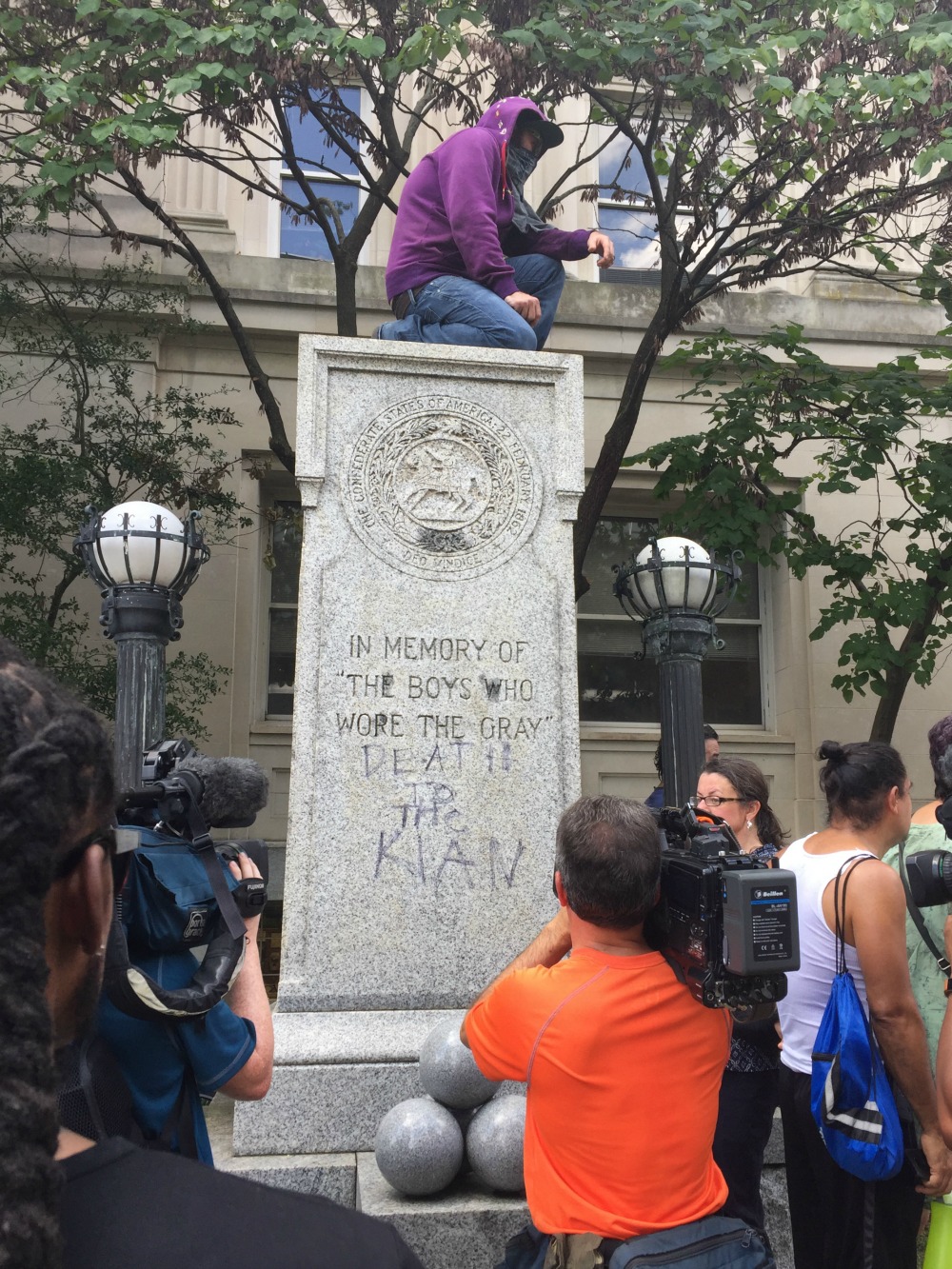

Eventually, the procession arrived in front of the old Durham County Courthouse, where a statue commemorating Confederate veterans was ceremoniously erected in 1924 and unceremoniously toppled Monday.

Not long after that came the tensest moment I witnessed. Two white men were on the lawn in front of the courthouse. I didn’t see how the confrontation started, but one of the men, who declined to give his name, said he was just waiting for a ride and hadn’t realized the protest was about to happen. He said a woman called him to unity (plausible) and then gave a black-power salute (also plausible).

“I said that ain’t no unity sign,” he said. “I decided to be smart-ass, for the first time in life,” and gave a Nazi salute. He said he meant it ironically, saying it was an equally divisive gesture to a black-power salute.

Predictably, this did not go over well with a crowd of hot and hyped up anti-white-supremacy protestors. Angry words were exchanged. The man insisted he wasn’t a racist: “I grew up in Braggtown,” a historically black Durham neighborhood. His friend, wearing a Peterbilt cap, yelled, “Allah owned goddamn slaves!” He also suggested a compromise solution: “Let’s tear down all the statues. Let’s tear down Martin Luther King and all of that shit. Let’s get rid of it all.”

“That shit goin’ get your ass whupped,” a protestor advised them. But a few protestors, as well as City Council member Charlie Reece, stepped in to make sure that didn’t happen. A few protestors stood between their angrier comrades and the men, and and others pushed belligerent fellow protestors away to defuse the situation. Someone threw water on the man in the Peterbilt hat, eliciting scolding from those around him. The men backed away and slipped into the basement of the old courthouse.

I caught up with them a few minutes later, a little way away from the action. They seemed, understandably, a little rattled from having faced down dozens of angry demonstrators. The first man, who admitted he’d given the Hitler salute, had a tattoo with an Iron Cross on his bicep, and work knife on his waist. He seemed to regret his gesture, but he had plenty of thoughts on race, though he complained that he’s profiled as a skinhead just because he’s bald.

“The problem is it’s not equal anymore,” he said. “Black Lives Matter and all that shit, it’s a terrorist activity directed by the Nation of Islam.” He encouraged me to look up Louis Farrakhan, the anti-Semitic and generally bigoted leader of that group.

He didn’t like the removal of the statue and offered an analogy I couldn’t quite follow. “If we put a watermelon and fried chicken at a statue of Martin Luther King, that would be racism,” he said. (True enough.) Peterbilt hat said the Civil War was fought to stop big government. (Significantly less true.) “If it really mattered that much to them, do some work in Africa,” the first man said.

That was the only real appearance by anyone openly espousing white-supremacist sentiments I witnessed. Later in the day, a new rumor circulated that the Klan had received a permit to rally at 4 p.m., but that turned out to be wrong. The lack of any real KKK presence was a matter of some debate. Was there ever a real threat? Was it a bluff? Or was it just a rumor run amok? The sheriff’s office did say it had received a threat and informed community leaders, and county officials closed their offices early. The Pelham KKK group has been known to announce protests and then not show up. Several crowd members speculated to me that the two men were sent to scout the situation, and having seen the crowd’s numbers, decided it was best to back off.

With no Klan protest available to counter-protest, the crowd became a big celebration instead. Estimates ranged as high as 2,000 attendees. It was a diverse cross-section of the Durham community: young and old, black, white, Hispanic, and Asian. There were hipsters with sculpted mustaches and band t-shirts, men with graying dreadlocks, black-clad anarchists with bandanas over their faces even in the heat, women in hijabs, and young men obeying the old Southern dictum: Sun’s out, guns out. There was a drum circle, of course, and more chants. Some people climbed up on scaffolding outside the building and just sat there, surveying the scene. Photographers amateur and professional roamed the crowd. Local TV journalists, and your correspondent, sweated through their dress shirts and then kept sweating.

The activists’ grim faces at 9:30 a.m. had turned to wide grins by mid-afternoon. Someone lit some incense. A young man roamed through the crowd wearing a fluffy white Versace robe with gold trim. It looked comfy but hot, and if he was trying to make a political statement, the message was opaque. Various people had brought in case after case of water—essential in the heat—and others had brought granola bars, snacks, and even aluminum trays of rice and beans. A few street medics lounged in the shade.

The police maintained a hands-off approach, much as they had as the statue was pulled down Monday. Durham city police and county sheriff’s deputies blocked off streets leading to the area, but the officers in uniform mostly stuck to the margins. Someone had scrawled “Death to the Klan” on the empty plinth of the Confederate statue. People had various reasons for their jubilation. I heard some exulting in Steve Bannon’s firing from the White House. Others gossiped about comments made by District Attorney Roger Echols, in which he implied he was skeptical about felony charges brought against people who pulled the statue down, citing both questions about the value of the statue under statutory cost levels, and about mitigating factors including community pain. Some people seemed to just be enjoying a Friday afternoon free of the daily grind, with a bunch of other happy people.

Later in the day, after I left, there was a more tense exchange between protestors and police. A group marched several blocks away to the Durham Police Headquarters. Officers in riot gear pushed the crowd back a couple blocks, WRAL reported, and then ordered them to disperse. One man was arrested for failing to disperse.

As I wrote after the statue was toppled, there’s been a heavy focus on the backlash to Confederate monument removal, and the ways that demanding to tear down statues (or, in Durham’s case, simply doing so) is only likely to further inflame cultural anxieties among conservative white Americans, many of whom polls show already feel that they are the subjects of discrimination.

But the last week’s events in Durham, from the statue’s removal on Monday to the improvised party on Friday, show that the backlash to that backlash—people who were outraged by what happened in Charlottesville and determined to keep it from happening again—is also a potent force. It’s a fragile, ad-hoc force, and the political disagreements among the members (from anarchists to I’m With Her types) might outnumber the areas where they actually agree. But there’s nothing to paper over divides like a hot summer day, a big party, and outrage at the Ku Klux Klan.