The whistleblowing site WikiLeaks has published the sensitive personal data of hundreds of ordinary people, including sick children, rape victims and people with mental health problems, an investigation has revealed.

In the past year alone, the “radical transparency” organization has published medical files belonging to scores of ordinary citizens. Hundreds more have had sensitive family, financial or identity records posted to the web, according to the Associated Press.

In two cases, WikiLeaks named teenage rape victims.

In a third case, which the organization disputes, WikiLeaks published the name of a Saudi citizen arrested for being gay – an extraordinary move given that homosexuality can lead to social ostracism, a prison sentence or even death.

“They published everything: my phone, address, name, details,” said another Saudi man who told the Associated Press he was bewildered that WikiLeaks had revealed the details of a paternity dispute with a former partner. “If the family of my wife saw this ... publishing personal stuff like that could destroy people.”

A tweet from the main WikiLeaks account denied that third charge, saying: “No, WikiLeaks did not disclose ‘gays’ to the Saudi govt. Data is from govt & not leaked by us. Story from 2015. Re-run now due to election.”

WikiLeaks did not immediately respond to a request by the Guardian for comment.

The organization quickly rose to prominence in 2010 when, in collaboration with the Guardian, Der Spiegel and the New York Times, it released thousands of classified US military documents that had been leaked to it by Chelsea Manning, who is still imprisoned for her role in the breach. (Manning also writes for the Guardian.)

The leak included a video of an American Apache helicopter gunning down a group of Iraqis, including several journalists, which became known as the “collateral murder” video. But the site, and its founder Julian Assange, have long faced scrutiny for their own collateral damage.

In 2010, Amnesty International, along with the Open Society Institute and the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission, signed an open letter criticizing the organization for its decision not to redact the names of Afghan civilians in the Manning leaks – a decision which showed what the advocacy group Reporters Without Borders described as “incredible irresponsibility”.

More recently, leaked material from the Democratic National Committee published in July carried more than two dozen social security and credit card numbers, according to an Associated Press analysis that was assisted by New Hampshire-based compliance firm DataGravity.

Two of the people named in the files told the Associated Press they were targeted by identity thieves following the leak. One was a retired US diplomat who said he also had to change his number after being bombarded with threatening messages.

WikiLeaks’ stated mission is to bring censored or restricted material “involving war, spying and corruption” into the public eye, describing the trove amassed thus far as a “giant library of the world’s most persecuted documents”.

Its library is growing quickly, with half a million files from the US Democratic National Committee, Turkey’s ruling party and the Saudi foreign ministry added in the past year or so.

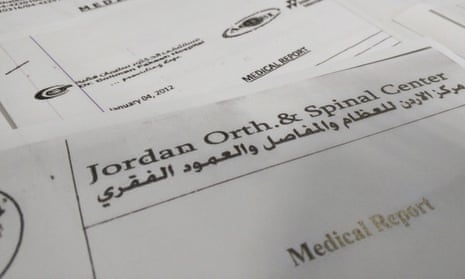

But the library is also filling with rogue data, including computer viruses, spam and a compendium of personal records. The Saudi diplomatic cables alone hold at least 124 medical files, according to a sample analyzed by the Associated Press. Some described patients with psychiatric conditions, seriously ill children or refugees.

“This has nothing to do with politics or corruption,” said Dr Nayef al-Fayez, a consultant in the Jordanian capital of Amman who confirmed that a brain cancer patient of his was among those whose details were published to the web.

Dr Adnan Salhab, a retired practitioner in Jordan who also had a patient named in the files, expressed anger when shown the document. “This is illegal what has happened,” he said in a telephone interview. “It is illegal!”

The Associated Press, which is withholding identifying details of most of those affected, reached 23 people, most in Saudi Arabia, whose personal information was exposed. Some were unaware their data had been published because WikiLeaks is censored in the country. Others shrugged at the news, and some were horrified.

A partially disabled Saudi woman who’d secretly gone into debt to support a sick relative said she was devastated. She’d kept her plight from members of her own family. “This is a disaster,” she said in a phone call. “What if my brothers, neighbors, people I know or even don’t know have seen it? What is the use of publishing my story?”

Paul Dietrich, a transparency activist, told the AP that a partial scan of the Saudi cables alone turned up more than 500 passport, identity, academic or employment files.

Lisa Lynch, who teaches media and communications at Drew University and has followed WikiLeaks for years, said Assange may not have had the staff or the resources to properly vet what he published, or perhaps felt that the urgency of his mission trumped privacy concerns. “For him, the ends justify the means,” she said.