It was the happiest time of the school year. Kate, which is not her real name, and her class of 12- and 13-year-olds would soon leave Aberlour House, their home for a third or more of their lives. Next term most of them would start at the senior school, Gordonstoun, a famously severe Scottish institution that Prince Charles had once described as “Colditz in kilts”. Fifteen children, all boarders and fresh out of exams, set off into the Scottish mountains for a week’s camping.

“Exped” is one of Gordonstoun’s traditions, born of the unique vision of the school’s founder, the educational innovator Kurt Hahn. A refugee from Nazi Germany, Hahn is most famous for founding the Outward Bound movement. But before that, in 1934, he set up a revolutionary new school in a dilapidated stately home in Moray, northeast Scotland. Schooling would include mountains, the sea, fresh air and soul- stiffening adventures.

Gordonstoun was a success, especially after Prince Philip of Greece, now the Duke of Edinburgh, arrived. Other royals followed: five of the Queen’s children and grandchildren went there, despite Charles’s complaints. By the 1970s it was touted as a place for spoilt or wealthy children who needed toughening up – Sean Connery and David Bowie’s sons went, and so did Charlie Chaplin’s granddaughter. Physical punishment, strict discipline and cold showers were key to Hahn’s approach to keeping children in line.

The school was notorious not just for being tough, but for bullying. The novelist William Boyd, who started boarding there aged nine, described his nine-and-a-half years at Gordonstoun’s junior and senior schools as “a type of penal servitude”. Smaller children were at the mercy of older ones and violence, theft and extortion were common. As part of his initiation at Gordonstoun, Prince Charles, aged 13, is said to have been caged naked in a basket and left under a cold shower.

In 1936, Hahn founded a preparatory school for Gordonstoun, to cater for children as young as seven. The regime at Aberlour House was not much softer. In the 1970s there was no central heating. Windows were left open at night: in the winter, the children could wake up with snow on their blankets. The school was separate, situated half an hour away, though Gordonstoun helped manage it. The schools shared a uniform, school song and the motto Kurt Hahn had devised: “Plus est en vous,” a contraction of a French phrase – there is more in you than you imagine.

Mutual respect, resilience and trust were the cornerstones of Hahn’s notions of how to educate a child. His ideas have made Gordonstoun one of Britain’s most famous public schools. But a series of complaints sent to me covering 40 years reveal a dark alternative history. Not all of the stories can be detailed here. But, too often to be excused, Gordonstoun and its junior school appear to have let down the trust of parents and failed to respect the rights and needs of children. Predatory paedophiles are a part of the history of many celebrated schools in Britain. But Gordonstoun’s story is particularly urgent because Scotland’s archaic laws around proving sexual assault dissuade victims from coming forward. They can mean predators, who might be brought to trial, remain at large and free to offend.

Kate arrived at Aberlour House on a bursary in the 1980s. She was nine years old. Initially she was bullied by other pupils for being poor and having a Scottish accent. But by her last year at the junior school she was a prefect – a “colour bearer”, in Hahn’s militaristic system. She was, she says, a perfect, docile product of the educator’s ethos. “I was a really good girl, I didn’t misbehave, I got on with my work. I was a good citizen,” she explains, a twist in her smile.

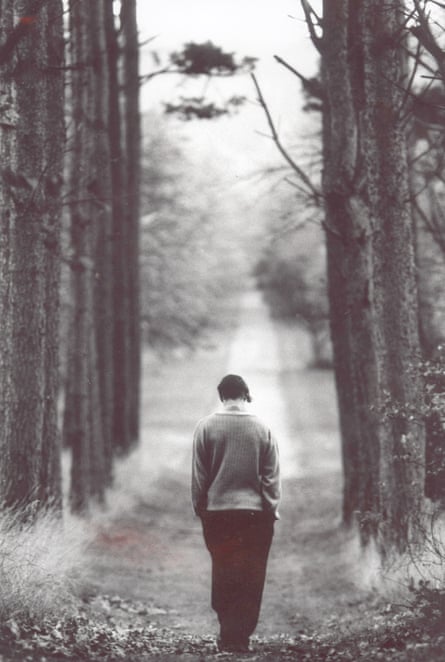

The lochside where the children camped saw the end of that Kate. What she says happened beside it has tarnished her life: an assault by a serial rapist, the trusted young teacher in charge of the expedition. Her most vivid memory of the subsequent summer days in the Highlands is of the moment when she went to a cliff-top, having decided to end her life. She was 12.

The exped was led by a male teacher. “He was young and everyone thought he was cool. We wanted to go,” remembers Kate.

Mr X, as we must call him, was in sole charge of the trip. As the excited children got ready in their dormitories at Aberlour House, he supervised the packing. He told them – as other witnesses told the police – not to bother with bathing costumes. “As a kid, I suppose, you just think – skinny-dipping! As an adult, you go… What?”

The exped set off in high excitement. “We got there, the banks of a loch, somewhere in the middle of nowhere and he said there weren’t enough tents. So, we were a tent short, which meant that somebody would have to sleep in his tent each night. We’d have to ‘rotate’.”

“At dinner-time we all had coffee and, a few of the girls, he filled their mugs with alcohol. I think it was rum. I felt a bit giddy. In the tent, the first night, it was me and two other girls. I remember being cold, wearing a jumper. And he started touching me, when they were still in the tent. I didn’t know what to do. I was totally frozen, scared. I pretended to be asleep thinking it might stop. They left the tent, they were embarrassed, they knew what was going on. So they went to sleep somewhere else and left me alone with him. They were just in another tent, they must have heard everything. So they all knew it had happened.

“I didn’t know what to do. I didn’t do anything. I was terrified. I don’t remember much but the pain, on my cervix… He wore a condom. What kind of a man takes a packet of condoms on a school camping trip?”

She didn’t confide in anyone. “It was awful. Five or six more nights. Nobody spoke to me. I didn’t speak to anyone.”

For the rest of the trip Mr X ignored her. One day, lonely and confused, Kate wandered away from the campsite, contemplating suicide. “I got to the edge of the cliff, completely on my own, in the middle of nowhere. I was going to do it, and then I just thought, ‘No. Actually, maybe, I won’t do this.’”

Kate then began to have an inkling that she was not the only girl targeted. “The girls who were bitchy to me already were more bitchy, led by Jane [which is not her real name]. She was, I realise now from what the police have told me, already in a relationship with him. And the other girls were her gang.

“Later on, X said he had to go down to the village for something. It was because one of the boys had to make a call to his parents. He said to this other girl, Jane, she had to come as well.”

This boy remembers the event well. “He bought us two drinks each – half-pints or pints. I’d never had alcohol in my life. I remember giggling about it with Jane. I think now that I was there because it would have been weird for him to have gone just with her, in a pub buying a 13-year-old drinks. It’s better if there are two of you.”

The boy believes that X’s relationship with Jane lasted a year or more. “Once I was with her in his bedsit in the school, chatting with him. I left the room, but I went back very quickly and the door was locked. When I knocked no one answered, but I knew they were in there.” This was just one of several incidents when X and Jane were in rooms alone, often with doors locked. “You don’t think much of it at the time, but something lodges, because you do remember them as something that wasn’t right – an adult and a 13-year-old.”

X continued for at least another year at Aberlour. He would occasionally see Kate in a corridor: “He was checking up on me. He used to say to me: ‘You’ll die before me.’ I’ve no idea what he meant.”

At Gordonstoun the following year, the bullying began. It was led by Jane and it was rooted in the rape at the campsite. Girls would sing a song in Kate’s hearing about “That night in the tent.” The rumours of what happened at the campsite spread. Both she and Jane subsequently changed their names by deed poll – not unusual for adults trying to rebuild themselves after childhood abuse.

Now, Kate can begin to understand the root of Jane’s antagonism. “I always had a feeling there was something there – and now I realise the extent of what happened with her and the reason why she bullied me so much. In some ways, she had it worse than me. She considered herself in a relationship with him. I suppose she was in love with him.”

When she was 16, Kate’s father died in an accident. She had always been close to him. When she was 14 she had tried to tell him about X. “I started by saying a teacher made a pass at me and he freaked out. I didn’t tell him any more, I didn’t want to hurt him.” His death hit her hard, and she ended up in hospital after overdosing on paracetamol.

“I was such a mess. Gordonstoun threatened to kick me out, after my father was killed, unless I had psychiatric help.” After treatment, she returned to the school and found that one thing had changed. The bullying, the gossip and name-calling stopped. But now, in her 40s, with her own children, Kate is still dealing with X’s assault.

“Just recently, I realised I’ve spent my whole life trying to prove I’m not his victim. I’ve always said it has not affected me. Not me, I’m absolutely fine. In actual fact it has given me some very unhealthy patterns of behaviour, and also feelings towards myself. I only realised this in the past year, on my own. I wanted to prove I wasn’t scared, of men, of sex. All that stuff. I wasn’t going to be the classic rape victim. I thought I had sorted it all out.”

There are other stories, too. At the age of seven, John also started at the school one summer in the 1980s. Kate remembers him: “Just the sweetest little boy.” He was following a family tradition: his father went to both Aberlour and Gordonstoun. John’s father remains a believer in Kurt Hahn’s philosophy of teaching trust and self-discipline. He is a member of the fundraising committee of the Kurt Hahn Foundation, which raises money for scholarships to the school.

Most of John’s memories of Aberlour are of happiness and success. He wanted to board and did well. He excelled at sport and passed the exams to go on to the senior school with a commendation.

After a year or two, a new teacher arrived to take charge of English. “An eccentric,” says another student from that time, “a know-it-all and a show off”. Derek Jones was a keen photographer and ran the photography club. Pupils remember him wandering the school, a camera hanging down to his belly, his hands resting on top. His wanderings took him to the sports changing rooms. Supervision of this place was the matron’s job. Nonetheless, “Jones would often spend prolonged periods around the changing rooms and in the shower room,” says John.

John got to know Jones well after he was cast in the 1988 school panto. Late one night in his final year, 1990, John left the dormitory seeking help. Two of his toenails had been surgically removed after being broken in a rugby match that afternoon, and the painkillers had worn off. Jones found him, took him into his bedroom and said that he could provide some special, very strong painkillers so long as John promised to keep it secret. “He told me if I told anyone he would get into trouble, while he was only trying to do me a favour and help me.”

Half an hour later, Jones assaulted John in his bed in the dormitory. After stroking and patting the boy, he reached under the covers, pulled down his boxer shorts and attempted to masturbate him. John, under the effect of the pills, tried to push the teacher off him. He found he could not speak. After minutes of panicky struggle, Jones stopped the fondling and put his head under the covers, turning on a torch. John heard a camera’s shutter click and click again. He believes Jones took half a dozen photographs.

After Jones left the room, John struggled to get out of bed. It took a while, but eventually he woke his best friend, Michael. He told him what had happened and together the two 12-year-olds went to Jones’s room to confront him.

The stand-off lasted an hour. Jones denied all. He said that John must have imagined it, as a result of the pills. John and Michael demanded the camera and the film rolls they could see on Jones’s desk. If nothing had happened, then surely Jones wouldn’t mind them getting the films developed. The teacher refused and eventually the boys, exhausted, went back to bed.

A few weeks after the assault, John was driving with his mother. They were both listening to a Radio 4 programme and a woman was talking of her abuse as a child. “I know just how she feels,” said John.

The parents took their child to see the much-liked headmaster, David Hanson. “I went with John,” his father told me. “It was obvious that the headmaster believed him. There was no reason not to. He referred the matter to Gordonstoun.” The police were called and interviewed John and other pupils and members of staff. Jones was sacked. John’s parents say that they were encouraged not to seek a prosecution. Going into a witness box might be damaging for their son.

The school promised that in return for co-operation over not insisting on prosecution, it would ensure that Jones never taught again. “We accepted that,” says John’s father. “It was adequate, because there was a categoric assurance, a cast-iron guarantee that under no circumstances would Jones ever again teach children in a school. He would be barred.” He adds that this pledge was repeated in a letter from Gordonstoun’s then bursar, George Barr.

When John returned to the school, Jones was gone, but things had changed. “There had naturally been a lot of gossip among the pupils. I felt eyes in the back of my head from other students. I remember being called a ‘homo’. I suppose in the eyes of some children I must have been a ‘homo’ to have ‘allowed’ it to happen. There was a fight arranged in the senior boot-room during break time and after that I was no longer a ‘homo’. The remaining time there was happy.”

But as he went on to the senior school, the wider repercussions of Jones’s assault became apparent. The head boy and sporting hero of the junior school now kept his head down. Crucially, his faith in adults was gone. “It changed me completely,” he says today. “I was a model student until that evening. I became a nightmare. If I was bored, I made mischief. I left Gordonstoun having failed my A levels, I didn’t go to university. My life since school has involved drug use, alcoholism and a distinct lack of belief and trust that those who say they will always be there, actually will.”

John eventually got on with his life and became a successful businessman. But he was not at ease: his sense that justice was not done back in 1990 exacerbated with the worry that Jones might have preyed upon other children.

The stories told here are not the only ones to stain Aberlour House and Gordonstoun. A startling series of allegations, dating back to the 1960s, has emerged in recent years. They’re not all ancient history. Kevin Lomas, a teacher at the senior school during Kate and John’s time was jailed in 2008 for sexual offences against young girls at a tutoring school he ran in Oxfordshire.

During the 16 years Lomas worked at Gordonstoun he had a reputation for inappropriate sexual activity: he was known for his fumbling attempts to kiss the girl pupils – “with tongue”. He, too, took children on exped. A Gordonstoun spokesperson told us: “There is no suggestion that Mr Lomas committed any criminal behaviour during his time at the school.” If there were, then or now, the school would inform the police.

Such events and others, coupled with the stream of recent stories about sex scandals and cover-ups in celebrated public schools, sparked talk among Gordonstoun’s ex-pupils. In 2013 some of them began a private Facebook group, discussing things that had happened at the school, “that you don’t see in the brochures and the class photographs”, as one of them put it. Rapes, of boys and girls, were mentioned. Kate started to receive messages from girls she had known, apologising for the gossip and rumours, for the bullying, and for not having done more to help.

The group eventually involved more than 100 ex-pupils. Acting in concert, they presented the school with a list of demands: it should do more to address bullying and sexual abuse, issue an apology to past victims and fund help for them and, notably, promise in future to report any incidents to the police.

John briefly joined the group, but left it, thinking the chatter was futile: “It was mainly about bullying, old classroom rows.” But he had already decided that he had to act on Jones: “I had a duty to make sure this bastard was not still out there doing things to kids.” So in February 2014 he went to the police. Their subsequent investigation stretched as far as New Zealand. Eventually, John was told Derek Jones could not be brought to trial or offend again. He had died in a car crash in Kenya, five years earlier.

But if that was any consolation for John, it was spoilt by the shock of the other information the officer – who has declined to comment – then handed over. Despite Gordonstoun’s solemn assurances, Derek Jones had gone on to teach, and potentially abuse, elsewhere. He had been forced to leave a school in Essex and had then surfaced and taught in Kenya. It is unclear what happened in East Africa, but former colonies there have provided a home for several predatory paedophiles sacked from English private schools – some of whom have gone on to offend again. Scottish police have identified both the Essex and Kenya school where Jones taught, but have refused to name them to the Observer.

John’s parents were horrified at the news. John’s father told me: “I trusted the school. They said they’d make absolutely sure he’d never teach again. They didn’t. And, if he did teach, that tells me someone at Gordonstoun must have given him a reference.”

The school told police that it could not find a copy of the letter the Gordonstoun bursar, George Barr, sent to John’s father, promising Jones would not teach again, because paperwork had been lost. It says that during this period, Aberlour had separate ownership and management. But one ex-head teacher of Aberlour from the time says that Gordonstoun staff were often involved in the junior school and that the two shared governors. (Since 2002 Aberlour has been fully merged with Gordonstoun). The school says it has co-operated with the police in its investigations into Aberlour House, Jones and Mr X.

“When the Facebook thing kicked off, says Kate, “my daughter had just turned 12. And I thought: ‘You know, she’s still got gappy teeth!’ And I actually started to see myself then differently, completely differently. For all these years I’d not seen myself really as a child. My daughter brought it home to me that that is what I was.”

Kate made a formal complaint, which was dealt with by the same police team who addressed John’s case. The subsequent investigation – again, Police Scotland won’t discuss it – turned up impressive numbers of witnesses with evidence to support Kate’s claim. Crucially, police also found Jane and interviewed her. She told Kate, indirectly, how grateful she was that Kate had come forward. An arrest was made and Mr X made his first appearance in court – a process which in Scotland is private – to face allegations spanning four years.

For nearly a year, Kate prepared herself for facing X in court. It was very hard: the prospect of seeing him again was anguishing. She’d already had to identify him in a police line-up. That had caused her near-collapse. A local policewoman was made her liaison officer and became an emotional support; one of the things she told her was that Jane had asked the police to pass on her thanks: “Getting X to justice was the best thing that ever happened to her.”

“When [the Procurator Fiscal’s office] rang me and said, ‘It’s all fallen apart,” I could not believe it. They were so certain it was all going to happen, that it was a done deal. I’d hung my hopes on the fact that it was. I was looking forward to it even though it would be horrendous. I knew I’d be a blubbering mess in court, but I wanted it and now it was taken away. I thought, how do I move forward? I still don’t know how to move forward. I’m angry I allowed the whole thing to dominate my life again. And now I know I haven’t got anywhere.” Unfortunately the case was dropped when it became clear that Jane would be unable to give evidence. Kate cannot help but feel bitter. “I want to have compassion for her and at times I do. I know she’s been through an awful lot. But it’s hard not to have dark thoughts.”

In truth, what has dragged Kate back to the horrors of her school days is not Jane’s inability to give evidence but an arcane piece of Scottish criminal law – the principle of corroboration. Under it two independent witnesses or pieces of evidence are needed to confirm the key facts of a crime – in this case the identity of the alleged rapist and the fact of the rape. This is far from easy with crimes that tend to take place in private, such as sexual assault and domestic violence – and as a result, Scotland’s rates of reporting of rape and convictions are among the lowest in the world.

Without forensic or medical evidence, prosecuting Mr X demanded two victims – Kate and Jane. The loss of Jane’s evidence was fatal to the case, because the offence was in Scotland. If the allegation against X had concerned an event in England, or almost anywhere else in the world, the case would, the Observer has been told, have gone ahead without the need for corroboration. In England, also, John, Kate and others who suffered at the school would be able to bring civil compensation cases if their allegations were proven.

No official is permitted to discuss the case of X, but we have established that a thorough investigation was carried out, involving many of the people who were present at the campsite as well as other teachers. Nothing other than the lack of a corroborating witness, after Jane’s withdrawal, emerged that might have derailed the case coming to court. The only consolation for Kate and Jane is that there is no bar to the investigation being reopened.

There is a simpler question for Gordonstoun and the 160 or more private boarding schools currently facing allegations about sexual crimes committed against their pupils – can they protect their children properly now? The Observer passed Gordonstoun’s lengthy manual of “Child Protection Policy and Procedures” to Mandate Now, a campaign group lobbying to make child-protection systems in British institutions effective.

It examined the document in the light of many others adopted by hospitals, schools, care homes and social services and gave it a score of 4 out of 10. “It is verbiage, containing a number of disturbing flaws, ” Mandate Now says. Reflecting the point made by the Gordonstoun ex-pupils, the report fails, it says, to make it clear that abuse or allegations of abuse need to be reported to an outside authority. Without that safety net, in place now in most British schools, cover-up always remains a possibility.

Gordonstoun says this complaint is irrelevant because the analysis is based on English practice. Its policy is based on Scottish government guidelines. A spokesperson said: “Pastoral care at Gordonstoun is highly regulated and is at the heart of everything that we do… Child protection is something we take very seriously and we are committed to providing a safe and nurturing environment for all our students. We have rigorous child-protection policies that have been developed with guidance from expert agencies. The latest independent report into the school… made particular reference to ‘the extremely positive health promotion and child-protection procedures’ in place at Gordonstoun.”

The response went on: “We want our students to take full advantage of all the opportunities available to them and they can only do that if they are happy.” That seems an admirable ambition – and a change of philosophy for Gordonstoun. For all the talk of service, honour, compassion and self-sacrifice in Kurt Hahn’s teachings, the great educationalist and his disciples seem to have put less weight on the notion that, to learn and grow, children need to be happy. And safe.

Some of the names in this article have been changed.

For more on this story go to theguardian.com/society/series/boarding-school-abuse

This article was amended on 13 April 2015 to clarify the principle of corroboration in Scottish criminal law

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion